(Photo by iStock/Orbon Alija)

(Photo by iStock/Orbon Alija)

In 2019, Joyce Craig, the newly elected mayor of Manchester, New Hampshire, was grappling with two major crises: The city was reporting an opioid-related death every few days, and chronic homelessness was rising. Mayor Craig charged a task force with addressing both these issues, as their causes and symptoms seemed to overlap. The task force included representatives from nonprofits, the business community, academia, and government, including city hall. While everyone agreed they needed to act urgently, perspectives on what the problem was exactly and how to solve it varied widely. Some people were primarily concerned about fatal overdoses, others worried about order and safety in public spaces, and still others emphasized the lack of economic opportunity and affordable housing. The mayor’s call to address these issues holistically made sense to the task force, but where and how should they start when the group was so divided and the problem was so complex?

In a previous Stanford Social Innovation Review article, we wrote about the importance and challenges of forming collaborations across organizational and sectoral boundaries in cities and shared our view on the steps collaborators should take to make progress toward a solution. The broad strokes of the work are getting the right people on board, agreeing (enough) on what the problem at hand is, developing a work plan, creating a structure of accountability, and taking time to reflect, learn, and adjust actions accordingly. However, even if collaborators are aware of these steps, just finding a starting point—an entry into the problem—can remain elusive. If our last article was a roadmap for collaborators, here, we try to deliver the keys to the ignition.

The Right Conditions

In our most recent Bloomberg Harvard City Leadership Initiative study on cross-boundary collaboration in cities, we sought to understand why and how some teams get stuck before they get started, while others find entry points to gain progress. We studied the early stages of 10 cross-boundary collaborations from cities across North America and Europe, each tackling a daunting social issue, such as gaps in mental health services, equitable economic development, affordable housing, and sustainable growth. We found that during this often particularly disorienting phase, teams whose members included varied perspectives, had confidence in each other, and were able to self-direct their collaborative work had a better chance of getting off the ground than those who didn’t. Without diverse expertise, it’s hard to look at all aspects of a thorny problem and determine innovative ways to tackle it; without trust, it can feel uncomfortable to try new things and cede some autonomy in service of the collaboration; and without a sense of agency, a group can become vulnerable to the dreaded endless deliberation without any action (“analysis-paralysis”) or waiting in vain for detailed directions from leaders with formal authority.

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR's full archive of content, when you subscribe.

How to Launch: Find Suitable Entry Points

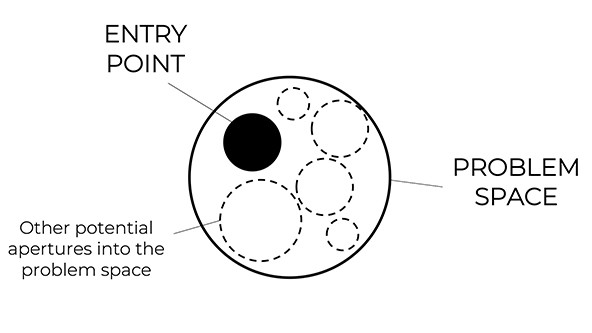

Once we gained an understanding of the conditions under which cross-boundary collaborators worked together best, we turned to observe what effective teams did to gain momentum. We found that the key to their progress was identifying an entry point—a meaningful, actionable, acceptable, and provisional opening into a large, complex, and partly unknown problem space. In Manchester, New Hampshire, the task force’s entry point to addressing homelessness and opioid addiction was to confront panhandling.

Initially, some people were skeptical about the idea of focusing on panhandling, because it might look like simply fighting symptoms, instead of focusing on the well-being of the individuals experiencing housing insecurity and opioid use disorders. Mayor Craig admitted, “I felt like we should be doing more, but I supported it because it was … a step in the right direction.” From our previous work and research with cross-boundary teams in cities, we know that some resistance to an entry point is common. After having realized and analyzed the complexity of a social issue, homing in on what seems like a tiny part of the problem can feel like work avoidance or cherry-picking. So, what makes a good entry point? From observing the 10 teams and systematically analyzing their actions, we discovered 4 characteristics of suitable entry points: They were meaningful, actionable, acceptable, and provisional.

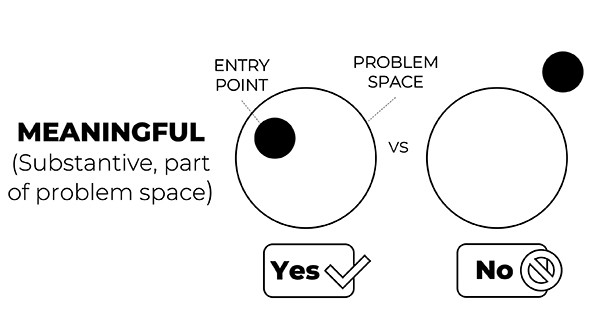

A meaningful entry point represents a concrete action that could have an impact on the larger issue, even if it doesn’t address the entire issue. For Manchester, addressing panhandling was meaningful in addressing one piece of the overall problem: Panhandling was a nuisance to some community members, including business owners and their patrons. It certainly wasn’t the only aspect the task force cared about, but Mayor Craig knew that whatever the city would do about homelessness and opioid addiction, there would be a link with panhandling and vice versa. Focusing on a concrete, visible part of the problem (that some very vocal members of the task force cared about) would allow the group to start working together and practice collaborating while building toward something bigger.

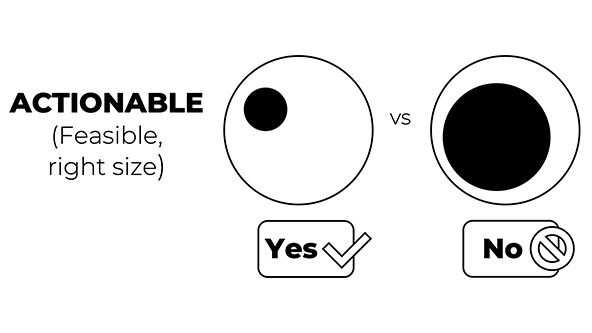

An actionable entry point means it can’t be too overwhelming or abstract to execute. In Manchester, addressing panhandling was well within the realm of possibilities for the task force. In 2020, the city and chamber of commerce launched an awareness campaign focused on discouraging donating to panhandlers and encouraging donating to care providers and other nonprofits.

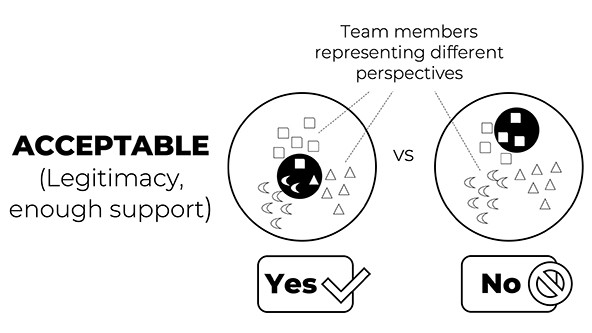

An acceptable entry point has enough support from the team and others to move forward. Addressing panhandling in Manchester brought many community groups into the work. Businesses wanted to discourage a nuisance, the city wanted to respond to residents, and service providers gained exposure through the awareness campaign.

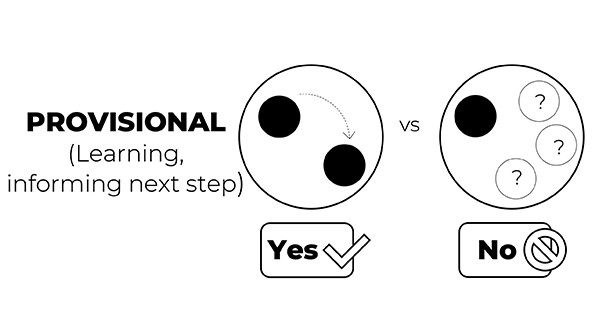

Lastly, a provisional entry point enables learning and generates clues as to which next step the collaborators should take toward a solution. Mayor Craig knew well that banning or discouraging panhandling would not solve the complex problems at hand. But the campaign brought parties together and helped them start on a path toward bigger steps and bolder action.

Mayor Craig said that while the task force started with panhandling, it led to more-formalized outreach in other areas, such as trying to tackle shelter and housing. The city’s fire department was soon regularly visiting homeless encampments to build trust and to try to direct people to services. Over the next few years, the city worked with some of the same partners from the task force to raise money for the first-ever, city-run shelter for 40 individuals, and to transform a vacant, state-owned building into a shelter for women run by the local Young Women’s Christian Organization. After hiring a new director of homelessness initiatives and a new director of overdose prevention in 2022, the city learned how connected the issues of overdoses and homelessness really were. “What we found,” said Mayor Craig, “is [that] 50 percent of the individuals who are overdosing in the City of Manchester are, in fact, homeless.”

Importantly, in Manchester, the task force’s entry point allowed the collaborators to gain momentum as they continued to work on other parts of the problem, including its links with drug-use disorders; mental health challenges; and a lack of emergency shelter beds and affordable and supportive housing. The Manchester example demonstrates that you can work on something concrete and manageable without losing sight of the larger problem and underlying issues. It also shows that it’s possible to take action while continuing to learn more about the problem.

As we wrote in a recent Journal of Applied Behavioral Science academic article, suitable entry points enabled collaborations to “set themselves on a path of discovery and learning-by-doing and move beyond analysis-paralysis, competing commitments, and performance anxiety.” Initial progress appears to breed confidence and capacity for further collaborative action.

Guiding Your Own Collaboration

The City of Manchester is not alone. Cross-boundary collaborations in cities across the world wade into complex, intractable issues uneasily at first, and then gain confidence and momentum to take on larger pieces of the problem. In the Netherlands in 2015, for instance, the national police and the public prosecutor’s office joined forces to crack down on organized crime and convened dozens of interdisciplinary professionals. One group of five members was assigned to the issue of illegal marijuana grow houses in residences in the City of Breda. The group included representatives from city police, a tax office, a power utility, and municipal public safety and security, as well as a public prosecutor. Although they talked past each other and frequently disagreed on the problem they were trying to solve in the early stages of the collaboration, they were able to coalesce around an idea to galvanize action in the community: fire safety. They devised a strategy that tapped into hyper-local power usage data and sent out teams to not only check on buildings using a dangerous amount of electricity but also educate residents on the fire hazards associated with growing pot. They knew it wouldn’t solve the problem of organized crime, but the entry point gave them a chance to engage with residents, many of whom were otherwise wary of government, and learn more about the problem for further action.

Back across the ocean in Louisville, Kentucky, a “rapid-response” team within a larger group trying to make higher education more equitable and affordable through scholarships found a way into their problem when almost everything was shutting down. When schools closed their doors during 2020, the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, many Louisville students had less-than-ideal home learning environments—sometimes with no Internet, no supervision, and little food. With such an urgent gap to fill, the rapid-response team carved out a much-needed offering: It began providing “learning hubs,” physical places supervised by adults where middle-schoolers and high-schoolers could use computers, have lunch, and access free personal protective equipment. While learning hubs were not the whole answer to equitable higher education attainment, they helped keep students on track and laid the foundation for later collaborations, particularly to build wrap-around services, such as tutoring, once schools re-opened.

While a perfect entry point might always be elusive, in most cases, collaborators can find a suitable one. Ask: Is the entry point meaningful in light of the larger issue? Is it actionable given the time horizon and capacity of the team? Is it acceptable to the main stakeholders? And is it provisional, in the sense that it enables the team to learn more about the problem and identify next steps? Remember, entry points don’t replace or diminish the broader issue area that a team hopes to ultimately address; they are a starting point for analysis and action.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Jorrit de Jong, Eva Flavia Martínez Orbegozo, Lisa Cox, Hannah Riley Bowles, Amy C. Edmondson & Anahide Nahhal.