(Illustration by Hugo Herrera)

(Illustration by Hugo Herrera)

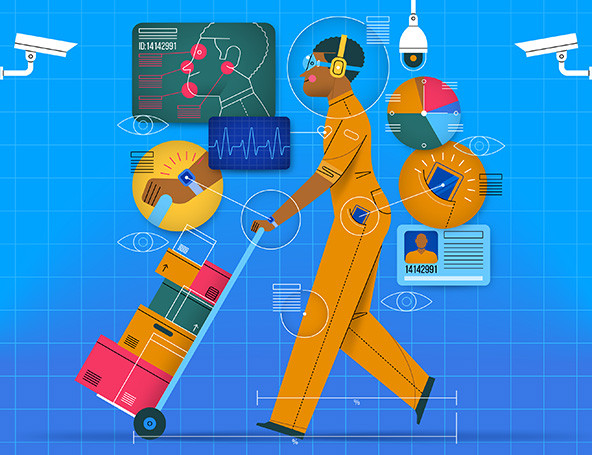

When Rina arrives at the Amazon warehouse, she swipes an employee ID. The sensors inside allow her past the door and then track her location as she moves through the giant facility each day. She chooses where to store her lunch strategically, since picking a break room too far away from her workstation will cut into her strictly monitored 30-minute lunch break. When she logs into that station—where she’s responsible for inspecting 1,800 items being shipped out each hour, and where her pace is meticulously measured by scanners on the conveyor belt—she knows she’s being monitored in several ways, by both human and artificial intelligence. Any non-mandated break, including going to the bathroom, is counted as “time off task,” which is also tracked by managers. If traffic on the conveyor belt slows down, Rina is supposed to request a new task, since downtime is also counted as “time off task,” and could lead to being disciplined or fired. When she leaves at the end of the day, she undergoes several forms of anti-theft screening, to make sure she’s not trying to take any company property home.

If you ask most people what “workplace surveillance” means, they’ll likely think of security cameras in large warehouses or retail stores, making sure employees don’t steal merchandise or fall asleep on the job. The reality is far more pervasive. These days, workplace surveillance certainly means being constantly watched, but it’s not just fish-eye camera lenses doing the recording. Rather, it’s built into the tools employees like Rina use every day to do their jobs, in all manner of industries. For the laptop class, it’s in programs that capture their keystrokes and allow employers to remotely view the websites they’ve searched on their browser. It’s in handheld scanners used by everyone from warehouse workers to retail clerks to hospital nurses checking into a patient’s room as well as the phone-based apps home health aides must log into and out of with every client they visit. There’s technology that records facial expressions and tone of voice to collect “mood and sentiment analysis” to measure employees’ affect and attitude. And the Black Mirror-esque implications of that monitoring cross socio-economic divides: In white-collar office jobs, it’s combined with AI-powered email and Slack message analysis to assess workplace culture; in offshore call centers, it’s paired with predictive conversation scripts to judge whether employees are responding to customer complaints with appropriate obsequiousness and pep.

While innovations like these are typically couched as a means of building a better, more efficient workplace, this level of technological creep threatens to turn workplace management into employee servitude.

In 2021, our organizations, Coworker and Data and Society’s Labor Futures Initiative, independently released two reports looking at the increased threat of employer surveillance technologies over the last five years, and particularly the last three years, when the COVID-19 pandemic led to many employees working remotely. In white-collar or administrative jobs, employers responded to the shift by requiring workers to install various forms of “bossware” on their home computers and by introducing a raft of other invasive new surveillance technologies into workers’ lives. Some mandated that remote workers keep their computer cameras and microphones on at all times during the workday, while others rolled out ostensibly health-focused apps and tools that track everything from step count and heart rate to sleep patterns and screen time. For blue-collar trades, workers were subjected to numerous mandatory new health screenings, from temperature checks to social distancing sensors, while still frequently lacking real protections against the pandemic.

In Data and Society’s report, “The Constant Boss,” we found that sweeping amounts of worker data today is tracked across myriad industries, collecting information about almost every aspect of their jobs and sometimes their personal lives, and often without employees’ full informed or free consent. Many workers, while generally aware they are being monitored, don’t know the extent of that surveillance or what is done with the information. In one example we learned of, Walmart employees were asked to install an app on their personal phones in order to check inventory but which required always-on access to the phone’s camera and location services, continually sharing information with employers unless the employee remembered to turn it off after their workday.

In Coworker’s report, “Little Tech Is Coming for Workers,” we found that, although most criticism of the technology sector focuses on the handful of “big tech” companies that dominate social media, in fact it’s the swarm of hundreds of small companies and vendors that are at the leading edge of introducing harmful technologies into the workplace. We analyzed and created a database of more than 550 tech products, companies, and investors developed in the last five years that are working to digitize all aspects of employment, from recruitment to hiring to productivity and risk monitoring, to see how radically these “little tech” corporations are changing the nature of work today.

This new marketplace is harming workers in various ways: by deepening and exacerbating the datafication of employment, which extracts more from workers while providing less in return; by increasing the potential for discrimination against employees on the grounds of race, sex, age or disability; by making it easier for employers to surveil their workers; by undermining privacy and collective organizing rights; by increasing opportunities to economically exploit workers; by commodifying workers’ data (including by using that data as a salable asset in case of a merger, bankruptcy or sale); and by merging home and work, making it harder for workers to disconnect from their jobs or sign out of employer surveillance.

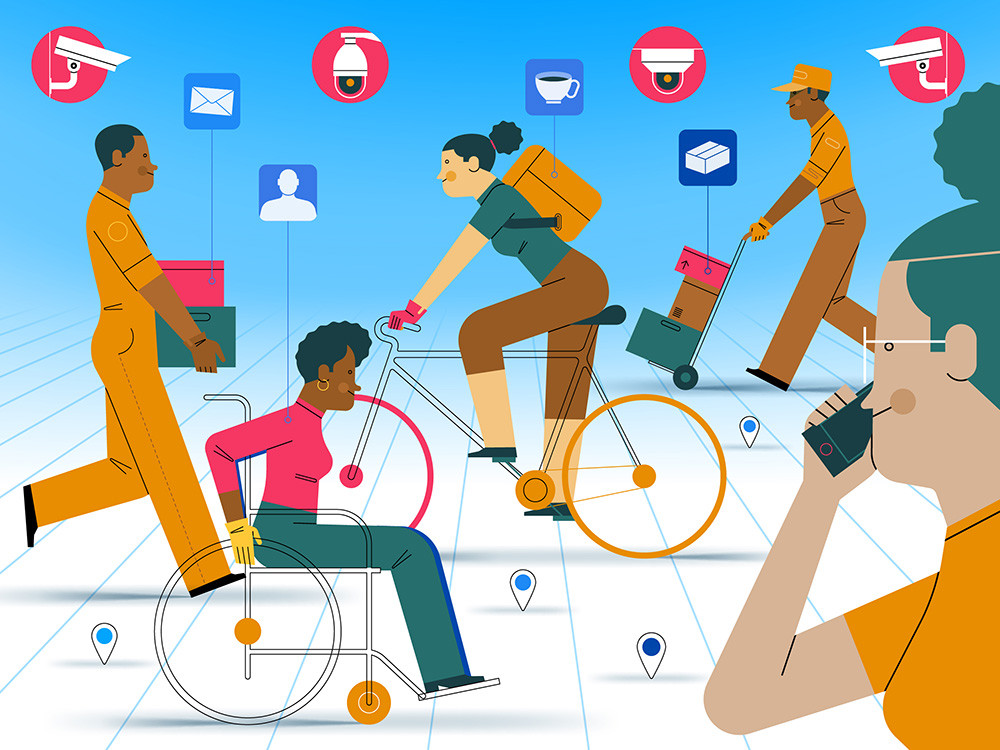

This sort of employer overreach started earlier than the pandemic, of course, and was particularly visible for workers in the gig economy: drivers for companies like Uber or Lyft, or contract cleaners for businesses like Handy.com, whose movements and customer interactions were digitized and tracked like never before (all while the corporations they labored for refused to classify these workers as actual employees). This is not simply an invasive business practice, but an operating principle to control workers and optimize for profits.

All of these risks are worse yet for the most vulnerable workers—workers of color, women and non-binary people, and immigrants—who are most likely to be engaged in low-wage work or the gig economy. And that makes sense, historically. Today’s high-tech surveillance technologies are exploiting the same loopholes in our labor laws that date back generations. If you look at the 1935 National Labor Relations Act, which guaranteed the right of private sector employees to unionize, the occupations excluded from the new protections then, such as farm and domestic workers, were overwhelmingly held by workers of color. Today it’s the same demographics being forced to work platform gig jobs, where they are similarly misclassified and thus exempted from workplace protections and subjected to pervasive surveillance.

Now, this level of surveillance—and the quantification of work it enables, along with never-ending calls for increased productivity—has broadened across the labor market. We’ve learned that it’s possibly to “Uberize” or “gig-ify” almost any job: breaking the work down into individual tasks, atomizing the people who perform them, and controlling those workers through systems that track their every movement while simultaneously shedding traditional employer responsibilities to offer a minimum wage, job stability, or any other benefits and rights the law requires.

The impact of surveillance on the ability to unionize is particularly worrisome, since the cornerstone of collective organizing—a right protected under federal law—is workers’ ability to talk to their peers and identify common concerns. In the past, the threat of firings, punishment for engaging in collective action, or corralling employees into a single location to make them listen to union-busting lectures were tried and true methods to thwart organizing. These days, workplace surveillance technologies have enabled bosses to spy on the places where worker conversations are taking place—from social media to online forums to private email listservs—and then to use mass emails and texts as a means of union-busting behavior. In one recent case, Amazon HR managers were caught infiltrating an employee listserv where unionization discussions were taking place.

Part of the problem is that the technology driving workplace surveillance is moving faster than policy and regulatory agencies can keep up. But many of the same things that make workplace surveillance such a daunting threat also reveal its vulnerabilities, and where workers and civil society might fight back.

Employers should be responsible for vetting the technology they bring into their workplaces, of course. However, the sheer number of “little tech” companies working in this sector makes self-regulation a mounting challenge. While regulatory agencies have been focused primarily on antitrust to address the rights of consumers, it’s clear these agencies have a critical role to play to monitor employers and enforce protections for workers. Given there are thousands of new companies dealing in AI, automation, gig-ification, and workplace surveillance, that conversation doesn’t fall neatly into the anti-monopoly policy discussions we have about “big tech,” but requires a multi-pronged solution. More broadly, we need a new framework for thinking about how to build the tech we want while centering workers’ rights, including effective protection of their right to privacy.

To some extent, the fact that historically marginalized workers are most likely to experience the most invasive and severe forms of surveillance at work means that there are specific avenues that regulatory agencies can use to offer protections, by assessing the impact of these technologies on federally protected classes of people, through the Americans with Disabilities Act and Civil Rights Act of 1964, strengthening these laws as needed to ensure that people are protected.

Unions and workers’ rights organizations also have a pivotal role to play here, and some are already stepping up and setting a precedent for governance. The Teamsters, which represent drivers for logistics companies like UPS, have fought to protect delivery workers from automated firings based solely on data gained through digital monitoring systems. UNITE-HERE has bargained to win data privacy protections for hospitality workers. The Workers Justice Project and Los Deliveristas have been fighting for a minimum wage for app-based food delivery workers in New York City. The Australian Rail, Tram and Bus Union has fought national proposals to mandate recording in all Australian public transport. And private sector UK unions have begun holding digital know-your-rights trainings for its rank-and-file members.

Philanthropies and the development sector have a role to play as well, from bolstering worker organizations, helping foster worker-tech collaborations, and working towards more equitable digital economies. As Ritse Erumi and Anita Gurumurthy write, the sort of tech we get will be the tech in which we invest.

The fact that surveillance technology is now affecting workers across industries and classes means that it’s both more imperative, but also more possible, to build multi-class solidarity between low-wage, immigrant and BIPOC workers on one hand and more privileged white-collar workers on the other. Cross-sector harms open the door to cross-sector collaboration. That’s exactly what’s needed to address these trends—in big and little tech, in startups, and across corporate America.

What does it feel like to work under constant surveillance? An Amazon warehouse worker joins the 2023 Data on Purpose conference to explain:

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Wilneida Negrón & Aiha Nguyen.