(Illustration by Hugo Herrera)

(Illustration by Hugo Herrera)

Hunger in the United States is more prevalent, more invisible, and more difficult to solve than many people would imagine. Nearly a quarter of Americans report experiencing regular food challenges, and more than 10 percent of US households are “food-insecure,” meaning they lack access to enough food to support an active, healthy life for all household members on a daily basis. As a result, 37 percent of adults received some type of food assistance from a nonprofit organization or a government service to help feed their household in the last year, according to a 2021 study by Impact Genome and The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research.

The problem persists because, despite spending billions on food programs each year, the root causes of hunger remain unaddressed. One key reason: Researchers rarely ask the hungry what they really need to maintain regular access to nutritious, quality food and so interventions aren’t accurately targeted to or measured against those needs. As a researcher in social impact, I’m focused on impact science—identifying interventions that create lasting impact across a range of social problems and measuring their cost per outcome, including food security. When it comes to stopping hunger, I want every penny to count.

At Impact Genome, we now have developed a tool to address the first part of the food security conundrum—identifying which specific outcomes are being achieved, by whom, where, and at what cost. It’s called the Impact Genome Registry, a repository for impact data on more than 2.2 million nonprofits and social programs in the US and Canada, including a portfolio of verified programs that address food insecurity. It’s how we can begin to use impact science to vet interventions, measure their cost, and create feedback systems to steer money to the most effective solutions.

Counting the Cost of Addressing Hunger

The idea behind an impact registry is to be able to catalog standardized data on outcomes, strategies, beneficiaries, context, cost, and evidence quality. With the Impact Genome Registry, we can quantify the annual impact—the number of specific outcomes and the total cost of producing them—of any social program. That helps people make informed decisions about where their charitable contributions can achieve maximum impact.

If we look at food security, there are a number of specific outcomes we’ve been able to standardize. This is important because each outcome represents a different aspect of food security, and the costs of the interventions needed to achieve them varies widely. For example, one standardized outcome, “As-Needed Access to Meals,” costs $5 to $10 to provide a single meal (this figure includes not just the cost of food but of all other expenses associated with the outcome, such as transportation, storage, and administration). But the cost to feed someone for a month (the standardized outcome “Regular Access to Food”) can range from $295 to $568. When we compare current spending to the reported need, we find a gap of at least $25 billion in government and nonprofit spending on what would be needed to provide every American regular access to healthy food.

So we aren’t spending enough. We’ve also learned we aren’t spending most of our dollars in the right place. By registry count, most of our tax and even our charitable dollars are essentially invested in giving a person a fish—access to food that is provided by local food banks or food pantries. Only a fraction of spending is focused on enabling people to fish—getting at root causes of hunger and thus achieving genuine, permanent food security.

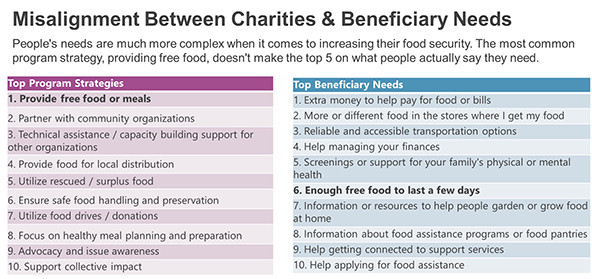

Gaining Insight From the Food Insecure

When our study with AP-NORC asked people who have experienced hunger what it took or would take to move to food security, we heard answers related to education and transportation: knowing enough to consistently buy healthy food and being able to get to places that sell healthy ingredients. Respondents asked for help in identifying nutritious food, or in learning how to prepare it. They requested affordable transportation to get to a quality grocery store and back to their homes. Some said they had no choice but to buy food at convenience or dollar stores, with a narrow range of fresh and healthy food choices. They said they needed more money to buy food and pay bills.

This is striking because it doesn’t match well with what nonprofits typically do to address food security. The most frequently used standardized strategies in the Impact Genome Registry are providing free food or meals, providing food for local distribution, and utilizing food drives or donations. This is a great example of how impact science can help us solve big problems. Because we were able to standardize the strategies used to solve food security, we were able to map the AP-NORC survey responses onto the strategies used by nonprofits and compare them. Now we have crucial information from people on the ground about what they need, structured in a way that can help funders find nonprofits that directly cater to those needs. This is the power of impact science—by using precise, standardized ways of describing what the problem is and how to solve it, we can make better, higher-impact decisions about how to allocate resources.

Example From the Registry

So what does a nonprofit program that uses needed strategies look like? An example from our Registry is The Food Trust in Philadelphia. This organization runs the Food Bucks Program, which provides high-need Philadelphia residents with access to 22 farmers markets located in low-income neighborhoods where access to healthy, fresh food is scarce. The trust’s Food Bucks are coupons that incentivize healthy purchases among Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) participants at farmers markets, increasing their purchasing power by 40 percent. For example, when a customer spends $5 at a participating farmers market using SNAP, they receive $2 in Food Bucks, redeemable for more fresh produce.

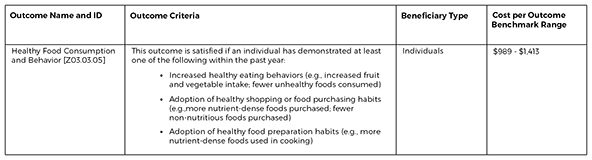

Here’s where impact science comes into play again. Because we have standardized the outcomes and strategies that programs in this space use, we can be very precise about both the problem that this program is trying to solve, and the strategies it’s using to do so. The Food Trust is not targeting the aforementioned, and common, standardized outcomes “As-Needed Access to Meals” or “Regular Access to Food,” nor is it targeting systems-level outcomes such as “Improved Food Distribution Network.” Instead, it’s targeting the standardized outcome “Healthy Food Consumption and Behavior” (more on that in the table below). This is important because it explains not just that the program is focused on food security, but which aspect of food security. This program is helping people learn to fish, using the earlier metaphor, rather than giving them a fish. Additionally, this program uses strategies needed according to our survey, by making it easier for people to get to a place that sells quality, healthy food, and by providing additional funds to buy food.

An example of a standardized food security outcome in the Impact Genome Registry, and the criteria required to meet the outcome.

Using Impact Science to Make a Difference

In short, impact science lets us determine whether we are spending enough money, and whether we are spending it well, in ways that can fix a problem. Clearly, getting to root-cause solutions requires identifying interventions that are effective at a cost that society can support. And they require listening to the voices of beneficiaries to make sure that the solutions provided are the same ones that are needed.

Key to solving hunger—or any big societal problem—is standardizing data about social impact programs in ways it can be acted on. The Impact Genome registry structures nonprofit impact data to this end. Starting with the specific outcomes nonprofit programs aim to achieve, funders can then see the cost per outcome and effectiveness rates, and also the strategies programs use to achieve the outcomes. Combining this with information on what people actually need to solve the problem paints the full picture of how funders can best support those solutions. It’s critical information like this that local governments, foundations, and private individuals are looking for to figure out how their funds can be used in the most effective way.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Heather King.