(Photo by iStock/Eoneren)

(Photo by iStock/Eoneren)

An enduring societal challenge the world over is a “perspective deficit” in collective decision-making. Whether within a single business, at the local community level, or the international level, some perspectives are not (adequately) heard and may not receive fair and inclusive representation during collective decision-making discussions and procedures. Most notably, future generations of humans and aspects of the natural environment may be deeply affected by present-day collective decisions. Yet, they are often “voiceless” as they cannot advocate for their interests.

Today, as we witness the rapid integration of artificial intelligence (AI) systems into the everyday fabric of our societies, we recognize the potential in some AI systems to surface and/or amplify the perspectives of these previously voiceless stakeholders. Some classes of AI systems, notably Generative AI (e.g., ChatGPT, Llama, Gemini), are capable of acting as the proxy of the previously unheard by generating multi-modal outputs (audio, video, and text).

We refer to these outputs collectively here as “AI Voice,” signifying that the previously unheard in decision-making scenarios gain opportunities to express their interests—in other words, voice—through the human-friendly outputs of these AI systems. AI Voice, however, cannot realize its promise without first challenging how voice is given and withheld in our collective decision-making processes and how the new technology may and does unsettle the status quo. There is also an important distinction between the “right to voice” and the “right to decide” when considering the roles AI Voice may assume—ranging from a passive facilitator to an active collaborator. This is one highly promising and feasible possibility for how to leverage AI to create a more equitable collective future, but to do so responsibly will require careful strategy and much further conversation.

The Promise of AI Voice

When it comes to decision-making, social innovation practitioners and scholars have highlighted AI’s potential to amplify efficiency and enhance creativity. At the same time, many have rightly raised concerns about fairness, biases, and decreased human control. In addition to these benefits and concerns, we contend that AI also offers a means to promote social good by giving a voice to unheard stakeholders in collective decision-making processes.

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR's full archive of content, when you subscribe.

Historically, collective decision-making has been valued for its ability to amalgamate diverse perspectives, fostering decisions that are often more nuanced and comprehensive than those formulated by individuals. This approach has been championed by entities like the United Nations, which promotes multi-stakeholder collective decision-making to develop more adaptable, viable, and extensive solutions within the framework of the Sustainable Development Goals.

However, traditional collective decision-making has limitations, often sidelining stakeholders for reasons of accessibility, discrimination, or convenience. Even when decision-making processes may be as inclusive as possible, they may still leave out important perspectives from those who cannot voice their perspectives, such as nature, animals, and future human generations. These later stakeholders play a critical role in (the future of) our society, and their exclusion from collective decision-making can result in solutions that lack depth and inclusivity. For example, within the climate debate, organizational and national decisions are often driven by short-term considerations, overlooking the long-term impacts on nature and future human generations.

Within this context, “AI Voice” emerges as an innovative solution, proposing a way to harness AI for positive social impact by collecting, processing, and presenting the perspectives of silent stakeholders. Initially coined as a term (in a paper co-authored by one of us and another colleague, Andrew Sarta) to describe AI-driven recommendations focusing on the concerns of oft-overlooked business stakeholders such as customers, “AI Voice” can be interpreted more expansively as the AI-generated human-friendly outputs, enabling AI systems to act as proxies for those unheard stakeholders. As such, this term does not denote a specific product or service but instead describes the output of certain AI systems, which can be utilized to give voice to unheard stakeholders.

For-profit organizations have already recognized the potential of using AI systems to enhance their decision-making processes, with several integrating this concept of AI Voice into their decision-making processes. As early as 2018, Einstein AI participated in Salesforce’s weekly meetings, offering executives visual sales and client insights based on customer relationship management data. Polish rum producer Dictador and Finnish IT firm Tieto have taken bold steps by designating AI entities in significant leadership capacities within their organizations. Similarly, several organizations are developing and deploying AI tools to facilitate group sense-making, deliberation, and ultimately decision-making.

Meanwhile, nonprofit organizations and consortia have been comparatively slow in adopting AI applications into their leadership and wider decision-making processes. One notable exception is the case of WWF’s recent initiative, “Future of Nature.” This London exhibition harnessed AI technology to project the possible futures of the UK's environment under various scenarios of human intervention. Here, AI Voice has been leveraged to articulate the perspectives and predicaments of nature. It acted as a narrator, vividly illustrating the grim potential future of the natural environment if the current pace of degradation continues. It also depicted the promising transformations that can occur if urgent, corrective actions are taken. This AI-generated output has also been used as a discussion tool, allowing stakeholders, including policymakers and activists, to explore and debate the potential consequences. In this capacity, AI has shifted from merely a forecasting tool to an active agent aiding in developing environmentally sustainable strategies. However, there is additional potential for further involvement of AI, such as a speech system that could directly contribute to these stakeholder discussions, giving a voice to the natural environment in the dialogue.

This innovative use of AI exemplifies the broader capabilities of generative AI, which stands at the forefront of addressing the perspective deficit in collective decision-making. Compared to traditional AI, which focuses on categorization and assessment, generative AI can generate seemingly new and creative outputs.

According to Demis Hassabis, co-founder and CEO of DeepMind Technologies, the output of generative AI can be categorized into three distinct types:

- Interpolated Output: Interpolated output refers to the generative AI's production of new data points or content that fits within the category of already observed data points of its training dataset. This output type is characterized by its similarity to the examples the AI was trained on. An example may be an AI trained to classify and generate new cat pictures based on a training corpus of cat photographs.

- Extrapolated Output: Extrapolated output, on the other hand, occurs when the AI steps beyond the direct boundaries of its training data to generate content. This output type involves inferences or predictions about data points outside the immediate training set. While still grounded in the underlying patterns learned during training, extrapolated outputs are more speculative, pushing the boundaries of the AI's learned context to create less predictable and potentially more creative content. An example may be AlphaGo, where, given all human knowledge about the board game Go, it plays millions of rounds against itself. Using the insight gained during that process, AlphaGo extrapolates new strategies never seen before in its training corpus (for example, Move 37 in Game 2 – AlphaGo vs. Lee Sedol in Seoul, 2016).

- Invented Output: Invented output is the generative AI's creation of entirely new content that is not directly derived from its training dataset. This output type showcases the AI's ability to innovate beyond learned patterns. An example may be an AI system trained in chess, creating the game Go.

Most commercial generative AI applications primarily produce outputs that align with the first two categories, interpolated and extrapolated. This is partly because there are limited mechanisms for effectively conveying the need for highly creative, 'invented' outputs to AI systems. Presently, AI struggles to process and act upon highly abstract instructions (e.g., designing a game that is easy to learn but offers complex mastery and can be completed in a reasonable timeframe). As a result, these systems often fail to generate outputs that reflect high levels of creativity. This limitation underscores the importance of domain experts, such as climate advocates or biologists, who can understand and engage with abstract concepts. Their role in providing context and interpreting AI Voice is crucial, bridging the gap between AI capabilities and the nuanced requirements of complex tasks.

The Multiple Roles of AI Voice

Not all AI outputs—and by extension, AI Voice—play the same role within a collective decision-making process. For instance, depending on the AI system’s level of integration within collective decision-making processes, an AI system may generate outputs that aid in organizing multi-stakeholder discussions or that offer previously unheard insights that contribute to complex deliberations.

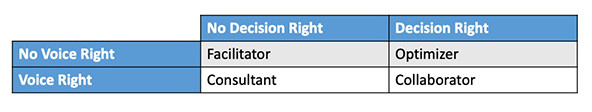

A useful way to classify these potential roles for AI Voice is to use a box matrix with the two kinds of rights—rights of voice (voice rights) and rights to decide (decision rights)—that humans may grant in the specific process. Voice rights grant AI the possibility to offer insights and analyses on operational and strategic matters. In contrast, decision rights empower AI to partake in the conclusive stages of decision-making, including casting a vote on initiatives. This differentiation leads to four specific roles that AI Voice can assume within collective decision-making processes: 1. Facilitator, 2. Consultant, 3. Optimizer and 4. Collaborator.

Facilitator Role: In the Facilitator role, AI systems operate without voice or decision rights. Their function is not to generate discussion content but to act as organizational tools. For example, an AI system in this role might compile inputs from various stakeholders before a meeting. Subsequently, as a proxy for stakeholders who are typically unheard, the AI Voice output might include an agenda that allocates specific time to address the concerns of these silent stakeholders. Additionally, AI Voice could be programmed to oversee the meeting, ensuring adherence to time limits and keeping discussions focused. This approach helps guarantee that the decision-making process remains inclusive and orderly.

Consultant: In the role of a Consultant, AI systems are granted voice rights but not decision rights. This means they analyze and interpret extensive data to advise decision-making processes but do not have the authority to make final decisions. For example, consider an AI system tasked with evaluating the impact of urban expansion on local ecosystems. This system would analyze environmental data and model various development scenarios, presenting findings and recommendations to minimize ecological damage. However, the final decision-making authority rests with human stakeholders. In this capacity, AI Voice provides stakeholders with in-depth, data-driven environmental analyses, thereby facilitating more informed decision-making.

Optimizer: In the role of an Optimizer, the AI system is equipped with decision rights but does not possess voice rights. While the AI does not suggest options or influence outcomes with voiced opinions, it is responsible for identifying the most effective actions based on goals and constraints. The AI objectively analyzes the information provided by stakeholders and employs a systematic approach to determine the optimal distribution of resources or the most effective solutions to problems, all within the framework of established efficiency metrics and criteria. For example, an environmental agency might deploy an AI system to allocate funding for conservation initiatives. The AI would assess each project against critical ecological performance metrics, such as potential improvements in species preservation or habitat quality. The AI Voice would then distribute funds in a way that optimizes environmental outcomes, ensuring decisions are made objectively and free from subjective bias.

Collaborator: As a Collaborator, AI systems are granted both voice and decision rights, allowing them to participate fully in the decision-making process akin to human members. In this scenario AI Voice contributes to discussions, proposes initiatives, and has voting rights on decisions. It actively engages in dialogues, introduces proposals, and votes on resolutions. For instance, AI Voice integrated into a wildlife conservation board might be tasked with analyzing and presenting data on at-risk species. This AI, representing the interests of wildlife, would propose strategies to protect these species based on its analyses. Furthermore, it would partake in the voting process, influencing the allocation of resources to ensure that the most effective strategies for wildlife protection are prioritized and given a vote.

While the Optimizer and Collaborator roles for AI Voice show promise, assigning decision-making rights to AI systems brings complex ethical considerations to the forefront. It is imperative to critically assess how and to what extent humans should delegate decision-making responsibilities to AI. This involves examining shifts in moral and legal responsibilities accompanying AI's use in decision-making capacities. Additionally, there is a need to develop robust frameworks that will effectively govern AI's conduct and ensure that its integration into decision-making respects ethical standards and legal requirements.

Strategies for a Responsible AI Voice

To ensure the responsible use of AI Voice and address its inherent challenges, we put forth three strategies: stakeholder and domain expert involvement, transparency, and AI literacy. However, these strategies should not be viewed as static recommendations but rather as encouragement for a continuous conversation about responsible AI for good.

First, stakeholder and domain expert participation is crucial in developing AI and utilizing any AI Voice output, acting as a critical line of defense against reinforcing existing biases. By incorporating a wide range of perspectives and feedback into the AI training process, the system is trained on a more comprehensive set of diverse experiences and viewpoints. Such inclusivity is a deliberate strategy to prevent skewed narratives and ensure perspective authenticity. For instance, without this breadth of input, AI-generated content may diverge from established ethical or societal standards, potentially resulting in confusion or harm. Additionally, while AI Voice may mimic speech patterns, it does not inherently grasp the complex human experiences it seeks to emulate. Therefore, domain experts are essential in scrutinizing AI Voice outputs, offering advice on system refinements, and helping to detect and rectify biases. Their expertise ensures that AI evolves in a way that aligns with broader social values and contributes positively to decision-making processes. These stakeholders and domain experts should also be entrusted with the critical task of determining the allocation of voice and decision rights to AI systems. This decision shapes the AI Voice’s level of influence and responsibility in collective decision-making scenarios.

Second, transparency in AI deployment is essential, especially regarding its use case and the sources of its training data. Open disclosure of where and how AI is used clarifies its influence and the potential reach of its decision-making. Similarly, clear documentation of the origins and composition of training data is fundamental to understanding the AI's potential biases and limitations. This level of transparency can pre-empt challenges related to trust and accountability by allowing stakeholders to anticipate and understand AI behavior. For instance, transparency can prevent the negligent use of AI in contexts for which it was not intended or in situations where its decisions could have unintended consequences. It also facilitates the identification of any gaps or overrepresentations in the training data, which, if left unaddressed, could lead to skewed AI outputs. Furthermore, transparency benefits AI systems by fostering user trust and facilitating more informed and consensual integration into decision-making processes. It creates an environment where AI tools can be more readily scrutinized, refined, and, if necessary, corrected by those with the relevant expertise.

Third, enhancing AI and data literacy among users is critical. It ensures that individuals and groups using AI for decision-making have the necessary understanding to engage with this technology effectively. Users with knowledge of AI's data processing can discern its strengths and recognize when its functionality might be compromised, such as when AI outputs appear inconsistent with expected norms. Being literate in AI enables users to question the validity of the AI's conclusions and to detect potential biases in its decision-making. This understanding is essential for ensuring that AI tools are used appropriately and that their decisions are integrated sensibly into overall strategies and operations. Furthermore, understanding the data that powers AI models allows users to advocate for data integrity and accuracy, contributing to the ongoing improvement of AI systems.

AI can act as a substantial force for good when implementing the necessary controls. Ensuring data transparency and improving user understanding of AI are critical steps toward responsible use. Engaging various stakeholders in the AI system design process is equally essential, particularly when allocating voice and decision rights to AI systems. By combining these technical and participatory strategies, we can leverage AI systems and AI Voice to address the “perspective deficit” in collective decision-making and create a more equitable collective future where future humans and nature can better thrive.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Konstantin Scheuermann & Angela Aristidou.