Advertisement for Cafritz homes in the Petworth neighborhood of Washington, DC. (The Washington Post, January 10, 1926)

Advertisement for Cafritz homes in the Petworth neighborhood of Washington, DC. (The Washington Post, January 10, 1926)

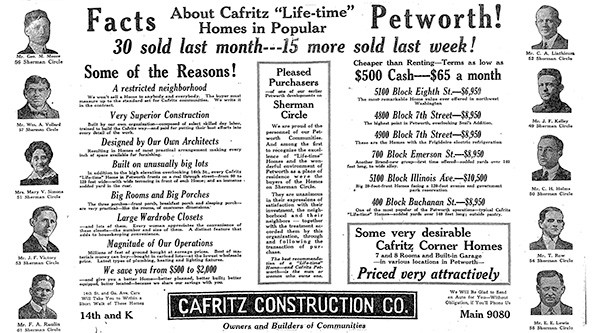

In early 1926, Cafritz Construction placed an advertisement in The Washington Post celebrating the speed with which their “Life-time Homes” were selling in the Petworth neighborhood of Washington, DC. Regular readers of the newspaper were likely already familiar with the development thanks to news articles that praised Morris Cafritz’s “vision and courage” and a constant stream of advertisements bringing his over 3,000 new units to market. Four years prior, Cafritz had purchased an over 38-block plot of land in a previously wooded part of town and promised to regrade the hilly landscape, pave roadways, and build houses at prices affordable to DC residents of moderate means.

This particular advertisement included a list of reasons why Cafritz homes were so popular. Perhaps potential buyers would be swayed by the “superior construction” or the “unusually big lots.” Maybe it was the “large wardrobe closets” or the promise that one would be “cheaper than renting.” Then again, maybe it was the signal that Cafritz’s Petworth homes were for white buyers only. If the images of 10 white “pleased purchasers” did not make that clear, then the promise of a “restricted neighborhood—We won’t sell a Home to anybody and everybody” certainly did.

Whether or not Cafritz held prejudiced views, he recognized the economic usefulness of restrictive covenants and benefited from a legal environment that encouraged discrimination and segregation in housing. By prohibiting any future sale of the property to Black or other non-white owners, restrictive covenants gave white buyers confidence that their homes and neighborhoods would remain white enclaves and therefore retain the “enduring value” that Cafritz promised for his “lifetime homes.” And it worked. By 1948 Cafritz had amassed such wealth from real estate development that he incorporated a foundation bearing his and his wife’s name.

Today, the Morris and Gwendolyn Cafritz Foundation focuses its grantmaking in the city and region where Morris built his wealth and where gentrification—in Petworth and elsewhere—continues to displace Black families at disproportionate rates. It is also one of several DC-area foundations profiled in a new report from the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy (NCRP) on “Philanthropy’s Role in Reparations for Black People.” The report (I served on the advisory committee that produced the report) makes the case—hardly unique to the Cafritz Foundation or to the DC area—that racialized harm is the source of capital behind contemporary giving and considers what is owed to people harmed in the creation of endowments. One takeaway: Traditional practices of grantmaking are insufficient.

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR's full archive of content, when you subscribe.

What does it mean to reckon—honestly and openly—with the source of philanthropic wealth? Doing so means considering the relationship between philanthropy and racial capitalism and acknowledging that categories of race are constituted and constitutive of capitalism and the creation of wealth. It also means engaging in historical research and accepting what historical evidence can and cannot reveal. Finally, it means linking racialized harms in the past with efforts at redress and repair in the present.

Philanthropy is starting to talk more about reparations. The conversations remain small and overdue, but recent momentum is notable with new organizations, publications, resources, and frameworks exploring how philanthropy can—and, in the eyes of many, should—engage the movement for reparations in the United States.

A subset of funders have started to shift resources into the hands of advocates calling upon the government to undergo a process of redress and repair. This move recognizes the federal government as, in the words of scholars William A. Darity and Kirsten Mullen, “the capable and culpable party” that set and enforced policies and laws to actively build the assets of white families and destroy the assets of Black families.

Another way to think about philanthropy and reparations—which is not mutually exclusive from the funding the advocacy for government reparations—is to consider whether foundations are also “capable and culpable.” In eras of both slavery and freedom, the accrual of wealth in the United States cannot be separated from legacies of extraction, violence, and denial of Black people and other minoritized groups. That remains true even if that wealth was donated to promote a public good.

Universities are starting to confront their legacies and ties to slavery. Georgetown University, for example, gained attention following the disclosure that the university owned and then sold 272 enslaved men, women, and children in 1838 to fund the university’s operations. Pressured, in particular, by student groups, Georgetown has created scholarship opportunities for descendants of the “GU272,” among other acts of reconciliation and repair. Now over 100 institutions of higher education have joined the Universities Studying Slavery Initiative with a commitment to researching and reflecting on their ties to human bondage and racism.

Foundations could follow this model. Admittedly, there are key distinctions between universities and foundations that make such a move unlikely and difficult. Philanthropic leaders are apt to highlight how few philanthropic endowments have such direct ties to enslavement since the legal infrastructure that creates and regulates foundations first emerged in the 20th century. They might also point to a lack of proof of harm as obvious as a bill of sale for human beings. Furthermore, without constituents like students to push for institutional acknowledgement or archivists and faculty to lead the research, foundations are more insulated from expectations of transparency and challenged to find and examine the historical record. Still, the uncomfortable work of researching, reflecting, and reckoning with the past remains necessary—and is possible. Sources do exist—often in the public domain—that support a case for philanthropic repair and redress.

Research into the origins of endowments means scouting, analyzing, and using evidence in ways that require both creativity—thinking expansively about where evidence might exist—and precision. The first, obvious place to look are in the archival records of foundations and the personal papers of their founding donors. Yet, the business practices that generated that wealth may or may not be included in such collections, which might be housed in a public archive or kept private. Local history centers, newspapers, oral history collections, and other repositories might hold records that detail “from below” how certain practices benefitted some and harmed others on the basis of race.

Consider again Morris Cafritz. Cafritz’s use of restrictive covenants is quite evident from a search of his advertisements in The Washington Post. Such language was sometimes thinly coded, with references to Petworth as a “refined and exclusive neighborhood,” with “precautions to keep out undesirables,” and “favorable restrictions for the protection of home owners.” Other advertisements touted a “restricted neighborhood” where “We write it in the contract.” One advertisement celebrated 23 Cafritz houses sold in 15 days “in the best restricted residential section” of the city. Both open and veiled discussion of covenants suggests they were seen as desirable to white consumers.

Historical research, no matter how fruitful, raises new questions while answering others. When that happens, the goal is to contextualize what direct evidence is available in increasingly broad concentric circles. To understand Morris Cafritz’s activities required reading on the history of Washington DC, on the history of real estate development, and on race and public policy. Critical questions include: What were the conditions that enabled the founding donor to amass such wealth? And, how did those conditions favor some over others? Of course, contextualizing the actions of wealthy individuals in the legal and economic landscape of their time does not absolve them of participating in systems of harm and denial.

An early Cafritz-built house in Washington, DC, c. 1916-1917. (Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, National Photo Company Collection)

An early Cafritz-built house in Washington, DC, c. 1916-1917. (Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, National Photo Company Collection)

Before 1948, restrictive covenants on property deeds typically prohibited the sale of the property to Black or other non-white buyers. Such clauses were challenged repeatedly in court but upheld on the grounds that the court had no authority over private transactions between individuals. (Coincidentally or not, Cafritz incorporated his foundation the same year that Shelley v. Kraemer struck down the enforcement of restrictive covenants.) Research in public records by local organizations such as Prologue DC further confirms the common use of these exclusionary mechanisms in Washington D.C.

This was not racism of the individual or interpersonal variety, though that certainly existed at the time and since. Rather, these practices reflected an assessment of housing values that believed the presence of Black people lowered the values of individual properties and neighborhoods. The connection between race and value was a core tenet of real estate even before the infamous Home Owners Loan Corporation maps graded and “redlined” individual neighborhoods. It was taught in economics textbooks and enshrined in 1924 in the code of ethics for the National Association of Real Estate Boards that prohibited agents from integrating neighborhoods by “introducing” members of a race or nationality not already present.

Research findings can also present surprises. Classified advertisements in The Washington Post reveal that Cafritz also rented and sold properties to Black families—he just did so within existing patterns of segregation, marketing units as “for colored” occupants. It was profitable to do so. As historian N.D.B. Connolly has written, “Racially dividing real estate generated wealth because it limited the mobility of consumers, thereby confining demand, manufacturing scarcity, and driving up prices on both sides of the color line.” That Morris could engage in such practices while also being charitable with his donations and serving in later years on the board of the United Negro College Fund is hardly a contradiction. As with any historical narrative, the reality was complicated and reflective of the workings of racial capitalism that removed personal animus or prejudice and instead structurally baked such preferences into the law, policy, and market.

Discrimination, racism, and segregation were key elements of Cafritz’s business strategy and resultant fortune that endowed his family’s foundation. There may not be a named plaintiff who was denied a home in Petworth and subsequently missed an opportunity to build wealth and equity in a “lifetime” home. But we know that such people existed whether or not we know their names, and we can consider how Cafritz’s use of covenants helped white families grow their assets (and his own), while denying the same opportunity to Black families. His boasting of covenants in the press, as well as his participation in professional and financial associations, also helped deepen and legitimize the association between race and real estate value in the D.C. region and beyond.

Whether the Morris and Gwendolyn Cafritz Foundation owes something today for actions in the past is not for me to say. I am neither an expert on reparations nor someone harmed by what Cafritz did and therefore should not necessarily have a role in designing what repair would look like or what shape redress should take. I am, however, a historian whose professional skills include the kinds of research necessary to inform how foundations go about acknowledging and understanding their past.

For a field like philanthropy that has been heavily influenced by economics and is eager to quantify and measure impact, the notion of handling fragmentary evidence may be unsettling. It is, however, a daily reality for historians whose professional skillsets include contextualizing what evidence does exist in larger patterns and processes. Even fragmentary historical evidence can reveal important, if painful, truths. What is needed in philanthropy, then, is a different—and more capacious—understanding of what “proof” of harm looks like and, perhaps, an acceptance of certainty and uncertainty co-existing.

If historical research is one part of my job as a university professor, teaching is another. When we discuss racism in my classes, my students consider a metaphor offered by psychologist and scholar Beverly Tatum. In her book Why Are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria? And Other Conversations about Race, she likens white supremacy and racism to “smog in the air….day in and day out, we are breathing it in.” She continues to say that we may or may not be at fault for creating the pollution, “but we need to take responsibility, along with others, for cleaning it up.” My students find this metaphor helps shift feelings of guilt, denial, shame, or resentment into action. I offer the same guidance to philanthropic leaders.

Current boards of trustees may not have created the racial wealth gap that is so pressing today. Nor, for that matter, were founding donors such as Morris Cafritz the only polluters. The point is not to shame or vilify; it is to recognize that we in the present hold a responsibility for the clean-up by interrupting cycles set in motion by others and which we may or may not be perpetuating. Foundations have the resources with which to do so.

As NCRP’s report on reckoning argues, “A reparations approach is a natural step for wealth-holding charitable organizations… [whose] mission is aimed at improving the well-being of people and communities.” That might entail rethinking how they operate, where they fund, what priorities they set, and who sits on the board. It might even mean conceiving of philanthropy differently: following models, perhaps, from the “land back” movement rather than models of charity or investment.

Foundations are unaccustomed to pushback given how the power hierarchies inherent in grantmaking replace criticism with gratitude and praise. Changing the norms of the field to discuss openly, transparently, and reflectively the source of the endowed wealth will not come easily nor comfortably and will take sustained support from both within foundations and without. Still, philanthropic entities have an opportunity—perhaps an obligation—to have an open conversation about racial capitalism in the United States and their relationship to it. That would be a true example of the leadership and social change that these entities so strive to achieve and a true fulfillment of their mandate to serve the public good.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Claire Dunning.