(Illustration by iStock/Kubkoo)

(Illustration by iStock/Kubkoo)

For as long as data have been collected in the United States, they have shown disparities in birth outcomes. In the US medical system, if a baby is Black, she is more than twice as likely to die as a white baby, regardless of her mother’s investment in education or prenatal care. For an Indigenous baby, the probability is only slightly lower.

Why is this? Funders have poured money into analyzing the age, education, prenatal care, genetics, behavior, and income of people having babies, but have not found meaningful answers. Indeed, a recent study of two million infants in the United States found that the babies of even the richest Black families are less likely to survive than babies born into the poorest white families. Despite significant financial investment and concerted national and local efforts to improve maternal health, disparities remain.

There is, however, a less-examined part of the picture, and it relates to social and intergenerational trauma. A growing research base indicates that social context across time can powerfully influence present-day health and well-being. If a baby’s mother’s-mother’s-mother generations ago had arrived on a slave ship from West Africa, statistics say she would be twice as likely to die as a white infant, and her mother would be three times as likely to die from pregnancy-related complications. Yet, if that mother had just arrived from West Africa to the United States, statistics show the baby would likely fare much better.

These data connect the social and generational experience of oppression (anti-Black and anti-Indigenous racism in the context of the United States) to birth outcomes. They widen the perspective from individuals’ physical bodies to systemic social experience, and from the present moment to experiences that occur over lifetimes and across generations. This, in turn, allows funders and innovators to move beyond solutions sourced from a single paradigm—one confined to the particular mother’s body and behavior—and to see a broader, and different, set of potential responses.

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR's full archive of content, when you subscribe.

Working From a Broader Perspective

Birth leader and midwife Jeanine Valrie Logan, founder of the Chicago South Side Birth Center, stewards a response to birth disparity that takes social and generational context into account. Her care for Black babies and their families is culturally centered, celebrating tradition and responding directly to anti-Black racism. It is holistic in terms of social context; it connects the person giving birth to resources, teaches them to understand their own body, and instills in them the knowledge that they are resourceful. It also includes babies’ families and communities in the face of generational experiences of harm; it recognizes where there are past traumas to heal, engages families during pregnancy, and equips them to be present and knowledgeable when babies arrive. Logan and her collaborators offer a model of birth care that World Health Organization data show reduces disparities and results in safe, full-term birth and healthy birthweight, care that sets a healthy trajectory for future generations. But beyond the impact of this approach, the challenge—and transformative possibility—is for funders to learn to recognize it.

Birth leader Jeanine Valrie Logan, founder of the Chicago South Side Birth Center. (Photo by Roger Morales)

Birth leader Jeanine Valrie Logan, founder of the Chicago South Side Birth Center. (Photo by Roger Morales)

At Chicago Beyond, we have learned that a more interconnected understanding of the social and environmental issues we seek to address increases the probability of successful outcomes. Our work with organizations like the Chicago South Side Birth Center reflects this. Chicago Beyond is a funder dedicated to supporting free and full lives, but first it is about humans who love humans. Liz Dozier founded the organization after many of the funny, bold, and precious Black youth she taught on the South Side of Chicago died in a cycle of violence that reflected systemic and generational trauma. This kind of violence still thrives in Chicago and far beyond. World Economic Forum analysis has shown that compounding inequalities related to things like property rights and wealth redistribution over generations drive violent victimization and sustain trauma globally.

Today, our work includes funding underrecognized, community-led work and systems change efforts. For example, we funded a partnership between justice leader Dr. Nneka Jones Tapia, the Chicago Children’s Museum, the Center for Childhood Resilience at the Lurie Children’s Hospital, and one of the largest single-site jails in the United States—an effort that has resulted in ongoing child-centered visits for the more than 70,000 children with parents who are detained at the Cook County Jail each year. The visitation model supports the mental health of the children, the reentry of parents into society once released, and improved morale among jail staff. Working from a broader perspective, the approach looks beyond the single paradigm of social services for children to address the generational interruption of parent-child bonds.

A Way Into Where We Need to Go

While these examples focus on children and families, understanding trauma and healing is an entryway into effective systems change across all issue areas. We define “trauma” as what happens when an experience overwhelms a person’s natural capacity to cope and recover. The focus is not on the external event, but on the wounding or pain people experience individually and collectively as a result of it. Trauma pervades every aspect of the social sector, including the people and institutions that comprise it. Those focused on education see evidence of trauma in data about student mental health and academic outcomes. Those working on environmental issues can trace trauma to human separation from the natural world.

As discussed above, this understanding motivates us as funders to leave behind familiar but limited, single-point perspectives and work from a more whole and systemic picture. It helps us recognize interconnections between individuals, families, communities, and systems; between past, present, and future; between physical, emotional, intellectual, spiritual, and ecosystem well-being; and between the work we do within ourselves and our own organizations and the issues we seek to change. It shifts what we fund, how we fund it, and the impact that funding has.

Yet the newly visible opportunities that emerge from this approach often do not align with traditional funding models, which can lead to frustration. Thus, an important aspect of integrating new understanding is to examine how existing processes constrain our thinking and ways of working. Here we outline five practical shifts funders can make to expand their perspectives, do less harm, and have a greater impact. They are based on seven years of learning and action alongside leaders working in their own communities, lessons from scholars from disciplines like systems thinking and ecology, and funders in both the Global South and North.

1. Widen the Funding Perspective

Targeting a single entity and framing individuals as the source of social problems creates blind spots and limits funders’ ability to support change. The solution to racialized birth disparity, as discussed above, does not reside in the mothers’ bodies, behaviors, educations, or incomes; it is rooted in an intergenerational system of oppression.

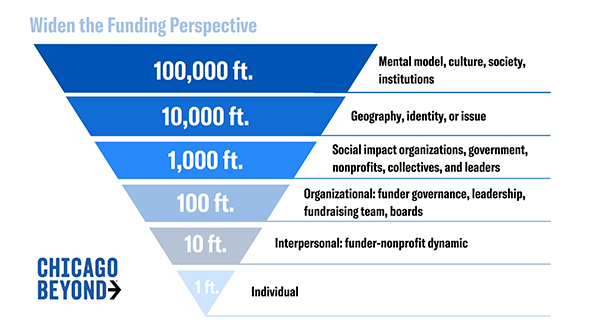

The first shift is therefore to actively engage a wider perspective. Widening perspective is more than appending new language to requests for proposals, and requires more from funders than a one-time listening tour or hiring someone with a particular identity. It is a practice that requires funders to work in new ways to recognize value in the unfamiliar. It embraces whole human beings within the broader social context, including individual and collective assets, strengths, and challenges; stops the search for a single solution; and provides a more accurate picture of problems and opportunities from which to strategically fund. Frameworks like the one below can help funders identify what levels of the system they need to learn more about, and audit where they have integrated multiple perspectives (firsthand and analytical, and present and historical) and where their viewpoint is unintentionally narrow.

This is one of many system models that funders can use; many traditional and Indigenous approaches recognize that the macro and micro are profoundly connected.

This is one of many system models that funders can use; many traditional and Indigenous approaches recognize that the macro and micro are profoundly connected.

Chicago Beyond has benefitted from actively examining what perspectives are built into or left out of any given guideline or process before applying it. Our practice also includes a cultural commitment to seeking out rather than reacting defensively to different vantage points, and funding and learning from unfamiliar community leaders. Inspired by the General Assembly of Boston Ujima Project—a member-run economic innovator that brings together neighbors, workers, and business owners—we created a People’s Assembly to help strategize and advise on our work. The group includes a dozen individuals who meet quarterly and participate not based on the power of their institution or title, but on the power of their community relationships.

2. Expand Institutional Knowledge and Metrics

The social sector is missing data, including data on how to foster individual and community well-being, and data from people heavily impacted by traumas. This is due in part to power dynamics between funders, researchers, community organizations, and communities, which can distort data access, validity, and value. Indeed, the ways the sector gathers and deploys data can generate harm. Overfocusing on what can be easily monitored from a distance often wastes money, time, and energy, and leads service providers to contort their strategies to fit. What is more, many funders believe that being a good steward of funds means funding “vetted solutions.” But often these solutions are effective only according to a chosen evaluation paradigm, the mindset and experiences of those doing the vetting, and the funder’s approach to risk (see shift number four below). If funders fund and evaluate initiatives based on a narrow range of institutional research, then the knowledge they work from will continue to be a closed loop.

Funders can, however, hold on to their intention to steward funds well and improve the fidelity of social sector data. To bring what is left out of the picture into view, boards and staff need to integrate the missing perspectives of people with firsthand experience of social problems into the knowledge they use to make decisions. Meaningful integration—unlike tokenism or using community engagement as a rubber stamp—builds the capacity of funders to recognize undervalued impact, enhance the agency of others, and work from a more whole picture in their day-to-day processes. Part of our strategy to expand institutional knowledge, for example, involves tapping into the power of networks to surface community-recognized leaders and work outside regularly funded nonprofits, expanding our awareness of approaches and strategies we did not know about, and enabling us to provide first-time institutional funding. The Roddenberry Foundation powerfully engages networks globally.

The same applies to metrics. By valuing organizations’ self-determination, participation in the collective, capacity to build relationships, and both context-specific approaches and quantifiable and scale-focused objectives, funders can better recognize the potential for systemic impact. This underscores the value of collective, generational, and multi-level approaches to metrics. Solely measuring individual outcomes can lead to treating humans like they are the social problem, thus, instead of focusing narrowly on whether the behavior of individuals improved, Chicago Beyond asks questions like: How does this investment impact the drivers of systemic harm? How does this organization leave others feeling empowered? How does this investment support what this community values, according to this community?

3. Fit Funding Processes and Terms to Purpose

Funding processes often require that communities seeking support document and recount trauma as a precondition to funding; the reward for telling the “best worst story” is resources. Historically, when reporting on the outcomes of social impact funding, funders have focused on individuals who succeeded despite overwhelming odds, emphasizing the role of the funder. This neglects to consider the kind of information—including systemic and generational traumas, and contributions and connections within the individual’s community that have fostered healing—that sets the stage for recognizing holistic solutions to the challenges a community faces. It also skews the frame by which funders measure success.

Funders must acknowledge the problems with practices like this and re-design their processes to encourage visioning and collaboration among community leaders, rather than performance of trauma and competition. Visioning can be difficult for adults, particularly for organizations and individuals used to documenting how their community’s traumas are worse than another’s to access philanthropic or government support. By demonstrating their intention and investing in facilitation and experience design, funders can help individuals and organizations develop trust, feel fully seen, and share their dreams and aspirations. Rather than asking people to spend time writing essays (a competency unrelated to the work they seek funding to do), for example, at Chicago Beyond, we work with groups seeking funding to understand who they are, their stories, and their numbers, and then write the funding proposals ourselves. Relationship-building is inherent to the process and creates mutual understanding as a starting point for funding. Shouldering this work honors potential partners’ experience and knowledge, and results in new clarity and useful documentation for the organization’s development and future funding.

The terms of funding are equally important. Flexible, long-term funding—an approach supported by practitioners, movements like Trust-Based Philanthropy, and data—allows change efforts to reach their potential sooner, and to broaden, deepen, and sustain the work and the people involved in it. Many people have observed this, and it is apparent in our work with organizations like Life After Justice. Life After Justice aims to eradicate wrongful convictions in the United States and is developing the first-of-its-kind direct service healing model for people who have been exonerated, all led by people who have experienced wrongful convictions. Receiving flexible funding to support adaptation over multiple years means that this transformative organization can invest in legal strategy and its healing model, and sustain its work and the people involved in it. It also means that it can build its foundation and pursue substantial new opportunities as they arise. Our partners have also valued add-on funding that explicitly supports the well-being of the people leading and doing the work.

4. Make Risk Analysis Whole

Unconscious patterns in human decision-making can lead funders to perceive greater risk in ideas, people, and organizational capabilities they are less familiar with. Often, funders also have the power to decide who bears risk and unconsciously shift risk away from themselves to their grantees—those with the least institutional power. This has the perverse result of increasing the stability of funding institutions while decreasing the stability of the people and organizations expected to deliver results.

Drawing on evidence-based processes that interrupt unconscious patterns in decision-making can help funders vet their rationales, decreasing the likelihood of devaluing high-potential leaders and efforts. In addition, if funders truly seek societal impact, they must consider not only the risks of grantees, but also risks to the broader community, and the risk of inadequate funding or stopping funding. By seeking out the perspectives of people who are proximate to social issues and inviting multiple vantage points, funders can identify and understand risks and mitigants they otherwise may not see and create a greater probability of success.

Analyzing our funding and developing tools to interrupt automatic thinking pushed us to shift from funding recognized nonprofits to intentionally funding underrecognized leaders, organizations, and ideas. In terms of risk, we have found that our hands-on development of funding proposals helps reveal risks and responses we might overlook. For example, after learning that delays in government funding posed problems for our partner Centro Sanar, a nonprofit providing high-quality, free mental health services to people on Chicago’s southwest side, we were able to provide a larger sum of initial funding that it could deploy as bridge funding when needed. This has helped Centro Sanar meet its payroll obligations to clinicians, who are absorbing significant secondary trauma in working with individuals and families to process complex grief.

5. Learn and Be Accountable

Funders tend to ask the questions and hold others accountable, which is why impact reports and metrics customarily focus on what nonprofits did or did not do. But as with other instances of limited institutional knowledge, this approach overlooks information funders need to assess and innovate. This includes ways funders inadvertently contribute to harm through internal processes and participation in an economic system that produces inequity and sustains trauma—the fact that funders are part of the social system that needs fixing.

The fifth shift is therefore for funders to use their institutional power and voice to acknowledge harm, and develop cultures of learning and mutual accountability within their own institutions. Camelback Ventures, for example, focuses on this. This means conducting regular self-inquiry: Did we do what we committed to do this year? Did we measurably improve our work as a funder? How does our culture, including the boardroom and workplace, reenact trauma or establish habits for healing? How do our actions contribute to systems change and healing? How do our processes contribute to harm, and how might we lessen this? How do we know?

Chicago Beyond strives to make regular, meaningful, feedback-driven improvements to our strategies, funding mechanisms, policies, and practices. Annual performance reviews for all staff at Chicago Beyond assess learning, and we make sure to translate regularly occurring reflection periods with our partners into action, including setting up on-the-ground services like food packaging and distribution to community networks during the COVID-19 pandemic, or supplementing funding to adjust for inflation. Sharing changes we make with our partners so that they can see their impact on us has propelled a virtuous cycle, helping us improve our work more significantly and faster.

From Unfamiliar to Possible

As funders seek to address social and environmental challenges systemically, it makes sense to begin by examining our role in them. Many traditional funding practices constrain our thinking and ways of working in a way that dramatically limits the potential for change.

Funders have many different strategies, institutional cultures, and attitudes toward power, participation, and trust. The five shifts described above can help funders increase our effectiveness at systems change and honor our commitment to being rigorous, accountable, and savvy about risk. By taking the funder out of the center and deepening engagement with individuals and organizations, we can widen our perspective of social challenges and solutions, ultimately so that funding can help humans and the natural world thrive long-term.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Shruti Jayaraman.