(Illustration by dane_mark)

(Illustration by dane_mark)

In 2015 the Supreme Court handed down a monumental ruling sanctioning marriage equality, allowing same-sex couples the same legal right to marry as opposite-sex couples. After the decision was handed down, journalist Ruth Marcus of The Washington Post penned an editorial, “Why there won’t be a gay marriage backlash,” arguing that “opposition to same-sex marriage is, literally, dying out.”

Six years after Marcus’ editorial, however, the accuracy of her prediction is questionable. According to a 2020 American Values Survey, 70 percent of Americans now support marriage equality, the highest ever and up from 61 percent in 2017. And yet the 2015 Supreme Court ruling triggered numerous laws targeting LGBTQ rights in the workplace, health care, housing, schools, and other public accommodation. For example, since 2016 several states have passed legislation allowing state-licensed child welfare agencies to cite religious beliefs for not placing children in LGBT homes. And at present, more than half of LGBTQ adults in the United States live in states without non-discrimination laws, meaning they can be fired because of their gender identity or sexual orientation.

Why has progress been accompanied by so many setbacks? The answer is that the manner in which things shake out is about more than just people: it’s about the system surrounding people, the context and conditions that prevent or support social change. In “The Water of Systems Change” we refer to six specific conditions within a social system: policies, practices, resource flows, relationships and connections, power dynamics and mental models. The coalition of proponents for marriage equality very explicitly focused on shifting each of these conditions in pursuit of their goals, and as evidenced by the 2015 Supreme Court decision, the coalition was tremendously successful for a period. Yet, like any system, the system surrounding marriage equality has been subject to what Canadian complexity theorist Brenda Zimmerman named “Snap Back.”1

According to Brenda, when trying to shift the patterns and behaviors in a system, it is important to acknowledge that systems naturally resist change. This is called system resilience, of which there are two kinds: engineering resilience and ecological resilience.

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR's full archive of content, when you subscribe.

A good example of engineering resilience is the way in which bridges are built: Since the builders want the bridge to have some “give” in a hurricane, they build the bridge to withstand shocks to the system, while also building in “give” so the bridge snaps back in place once the storm is past.

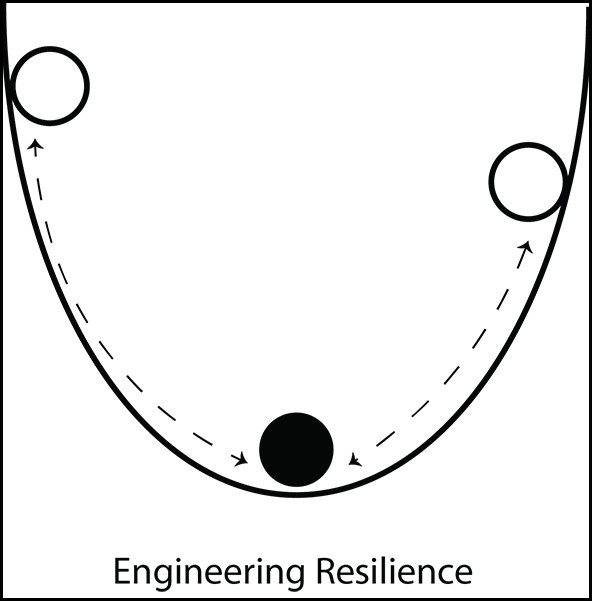

In engineering, maintaining the status quo is the point: If a bridge sways in high winds, it should be built so that it sways back when the winds pass. One way to illustrate the dynamic is to think about a marble in a bowl, as in the illustration below. The marble is in equilibrium when it is in the center of the bowl, but as the bowl tips one way or another the marble moves off equilibrium. As long as the side of the bowl is high enough, the marble will roll back into place. For an engineer, this is desirable.

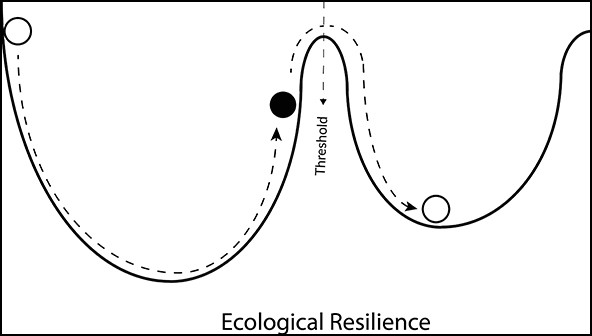

By contrast, ecological resilience models the way systems adjust to changing conditions, often by finding new equilibriums. Unlike bridges, natural ecosystems like ponds, oceans, forests do best when they are able to adapt and change, moving from an initial equilibrium to a new equilibrium as context demands.

For systems thinkers, finding a new (and more desirable) equilibrium is the goal. As with the first example, if the walls of the bowl—or the threshold for change—is high enough, the marble won’t make it over the threshold to a new state of equilibrium. It will snap back to its existing equilibrium. However, if you can find ways to lower the threshold (in this case, walls of the bowl), the marble can jump to a new equilibrium when rocked. With a new equilibrium, snap back to the initial equilibrium becomes less likely.

If, in your work, you have been strategic and effective enough to shift the equilibrium of a system—as LGBTQ rights activists did through achieving the 2015 Supreme Court decision—a key subsequent goal should then be preventing the phenomenon of snap back by stymieing a return to the previous equilibrium.

What are some principles to consider if you are trying to prevent snap back?

Snap back happens at multiple levels of a system: the individual level (an individual accepts, then rejects a new job definition), the organizational level (a nonprofit’s staff embraces then pushes back on new strategy), the initiative level (the power players in a city shift to more inclusive community engagement and, seeing its challenges, revert to more authoritative decision making), or the societal level (a global movement to adopt stricter carbon standards backtracks in implementation). But to keep snap back from occurring, at any level, focus on strengthening the resilience of the system’s new equilibrium while, as much as possible, weakening system resilience, or “muscle memory,” of the old equilibrium.

Here are a few strategies:

- Solidify new mental models (deeply embedded ways of thinking and doing that drive behavior) that you may have established. A key success factor in the marriage equality movement was shifting the popular frame regarding marriage equality from “same-sex couples should have equal rights” to “two people in love should have the right to get married.” The shorthand for this strategy became known as “love is love.” The shift in frame was to focus on empathy rather than anchoring people in their respective cultural values. What turned the tide of public opinion wasn’t a theoretical argument but an invitation for connection, speaking to the heart rather than to the head.

- Establish new relationships between people in the system who are not currently engaged with each other. Othering takes place when one group of people have minimal contact with another group and begin to see the other group as different, inferior to themselves, and “the cause of the problem.” Othering of queer people remains prevalent in the United States, even though the majority of Americans know someone in their family, at work, or through social activities, who identifies as queer. For example, othering was on display in the 2018 Supreme Court case introduced by a Colorado bakery owner who refused, for religious reasons, to bake a wedding cake for a gay couple; the restaurant owner won the case. There is a growing body of work on how to address othering.

- Support those who are marginalized in attaining positions of authority and power, in order to influence decision-making and the public narrative. As members of the LGBTQ population become more visible in positions of power, they help solidify the shaky equilibrium that exists today with regards to marriage equality and other LGBTQ rights, diminishing the odds of virulent snap back. Two exciting steps forward in this respect have been President Biden’s selection of Rachel Levine, a transgender doctor, for assistant secretary of health and human services, and of the 2020 presidential candidate Pete Buttigieg as secretary of transportation, marking the first instance of an openly gay cabinet secretary.

Our understanding of how best to prevent snap back remains a work in progress, and every systemic situation has its own dynamics. For example, one important perspective put forth by many in the LGTBQ community is that the strategy to pursue marriage equality was not sufficiently comprehensive or attentive to the needs of the larger LGBTQ community to mitigate snap back. This line of thinking suggests that the marriage equality movement diminished the ultimate goal for LGBTQ activism, which is to be fully accepted as different—“not like you”—versus being accepted as “more similar to you than you may think,” which was the “love is love” marriage equality strategy. As a result, many LGBTQ activists believe that, despite the positive marker of marriage equality becoming the law of the land, snap back was inevitable since the many underlying biases against queer people—particularly gender-nonconforming individuals, trans people, and queer people of color—were not sufficiently dealt with through “love is love.”

As you consider your systems change efforts, where should you be vigilant about preventing snap back? What strategies can you employ to increase the odds that snap back doesn’t occur in your situation? As you pursue system level strategies, how can you best consider the larger systemic context that could expose the underbelly of your assumptions?

1 Brenda, who coined the term, passed away too soon in 2016, while we were workshopping the concept of “Snap Back” with the intent to co-author an article on the topic. The past five years have compelled me to return to this concept in the hopes that it may be of use to systems change strategists in their work.

Correction: June 18, 2021 | This article has been changed to update an earlier statement that Pete Buttigieg was the first openly gay presidential candidate. Fred Karger was first, running in the 2012 GOP presidential primaries.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by John Kania.