The Prize: Who’s in Charge of America’s Schools

Dale Russakoff

246 pages, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2015

Newark, N.J., has long been home to one of the most expensive and least effective public school systems in the United States. The Newark school district spends more than $20,000 per student annually (nearly double the national average). For decades, the schools in Newark churned out substandard results, even as the district swelled to become the city’s largest employer. Graft and incompetence led the state to take over management of the district in 1994, but not much changed in the ensuing 15 years.

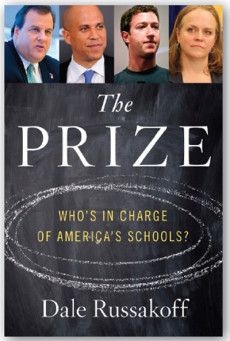

Against that challenging backdrop, three high-profile figures—Chris Christie, governor of New Jersey; Cory Booker, mayor of Newark; and Mark Zuckerberg, founder of Facebook—made a huge bet in 2009 on an education makeover project. Dale Russakoff, a former reporter for The Washington Post who has also written for The New Yorker, spent several years following the Newark school reform effort at close range. She chronicles the highs (which are few) and the lows (which are many) of that effort in The Prize.

The book opens as Christie and Booker join forces to change Newark’s schools. Their plan is to make a big bet on the charter sector by closing down under-performing and under-enrolled traditional schools and replacing them with what they hope will be higher performing charter schools. They enlist the support of Zuckerberg, a recently minted billionaire, and he makes a $100 million gift, which the three of them announce on The Oprah Winfrey Show. Then, using the long arm of the state’s power over the Newark district, Christie and Booker begin to make policy changes—often over the objection of locally elected officials. What could go wrong?

The Prize offers a cautionary tale of hubris, top-down autocracy, and poor execution. It offers an in-depth look at how education reform has played out, amid bare-knuckled political battles, in one American city. Early reviews of The Prize have treated it as part of a proxy fight in the education wars. That’s too bad. We should regard the book not as an excuse to confirm preexisting biases but as a vehicle for discussing what we can do to transform schools.

Indeed, Russakoff is at her best when she acts as an equal-opportunity critic. She skewers reformers for their worst instincts. But she also takes dead aim at the corruption and abject failure that characterize many public school systems.

I’ve spent more than 20 years in public education, most of them squarely in the education reform camp, and I found it painful to read as Russakoff lays bare the worst sins of the reform movement. She details Booker’s private jet trip to Sun Valley, Idaho, to woo wealthy patrons. She describes a reform proposal drafted by McKinsey & Co. consultants. (“It was titled ‘Creating a National Model of Educational Transformation.’ On the cover was a color photograph of Booker surrounded by African American children, all reaching skyward, as was the mayor,” she writes.) She recounts the chaotic early phases of the reform project. “I’m not sure who our client is,” one consultant says during this period.

Behind all of this ugliness lies a core truth that supporters of education reform need to acknowledge. Too often, reformers obsess about policies and overlook execution. They embrace technocratic fixes at the expense of on-the-ground training and organizing. And they are too readily seduced by the trappings of (say) an Aspen Institute retreat. All of this creates an inauthentic, above-it-all aura that people can sense a mile away.

At the same time, Newark’s traditional public schools are a longstanding disaster. Russakoff describes custodial contracts that siphon off so much money that schools can’t hire art and music teachers. Teachers’-union leaders demand extra back pay merely as the price for coming to the bargaining table—and wind up opposing reform anyway. Only half the money that the Newark system spends each year ever makes it to the schools; the rest of it bleeds out in layer after layer of bureaucracy.

Cami Anderson, the superintendent charged with implementing the Newark reform effort, arrives halfway through the book. By that point, miscues by state officials over the course of two decades have poisoned the environment for reform. Ultimately, local resentment drives her from office: The primal scream of opposition to state-imposed control drowns out news of the successes that occur during her tenure.

Although The Prize sometimes reads like an obituary for Newark school reform, the book sells short the accomplishments that people have made over the past five years. Newark has seen a significant increase in graduation rates, notable growth in the number of high-quality charter schools that serve poor kids, and critical upgrades in the training and autonomy given to principals. We may lament the politics, but it’s wrong to write off the results.

Russakoff makes a plea for more community engagement, but in doing so she glosses over some ugly realities. In many cities, there is a cottage industry that consists of people who turn community engagement into favor-trading and community meetings into Kabuki theater. Joe Nocera, a columnist for The New York Times, suggests that Zuckerberg has “learned his lesson” and will right the philanthropic ship by listening to communities. If only it were that easy!

It will be a shame if budding philanthropists read this book and decide that transforming public education is just too hard. It will be equally unfortunate if education reformers skip the book and avoid its critique of their movement.