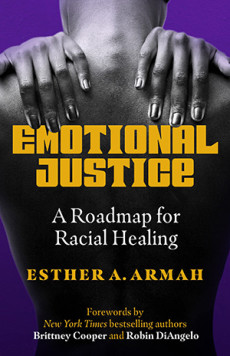

Emotional Justice: A Roadmap for Racial Healing

Esther A. Armah

192 pages, Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 2022

I have been reading about The Great Resignation—the term describing the exodus from the world of labor for thousands due to COVID-19. For Black women, what we need is “The Great Re-Definition.” We need to redefine Black women’s relationship to labor, and we urgently need to institutionalize wellness. In my new book, Emotional Justice: A Roadmap for Racial Healing, I call for an intimate revolution when it comes to labor for Black and Brown women.

Intimate Revolution is one of four Emotional Justice love languages designed to make racial healing a sustainable, systemic engagement, and not just a box-ticking exercise that disregards entrenched systemic inequity, and the emotional life that sustains that inequity. It’s got to be over for “grind.” We need to build a future where labor and work is not the sole determinant of worth—that’s why Emotional Justice matters. It gives language to the emotional world of our history, politics, racial justice, and what I call “the language of whiteness.”

COVID-19 upended our worlds in unrecognizable and unimaginable ways. Emotional Justice offers sectors and organizations crucial space to grapple with how history’s legacy of untreated trauma shapes work cultures and supports debilitating emotional labor by Black women. What that looks like is the ongoing labor roles assigned Black women—mammy, wench, welfare queen—such historical labels were nooses around Black women’s necks. In today’s world of labor, there is a contemporary manifestation, the “emotional mammy,” a workplace where Black women are expected to take care of the feelings of all white people, of all men, no matter the cost or consequence to them or their health. No more.

It is time for Intimate Revolution, it is time for EMOTIONAL JUSTICE.—Esther A. Armah

* * *

Intimate revolution means Black women globally unlearning the language of whiteness that teaches them that their sole value is labor. Unlearning whiteness for Black women globally means redefining their relationship to labor, normalizing and culturalizing rest and replenishment. It means unlearning emotional currency—having your value treated like a commodity.

The Breakdown

Intimate revolution is about the emotional work of changing Black, Brown, and Indigenous women’s relationship to labor. This emotional work for Black and Brown women is deeply complicated precisely because it is a relationship.

Labor in this case is not about a nine-to-five job that ends. It’s much more than work; it is about worth. It is about an emotional connection, a relationship at the intersection of history, gender, Blackness, value, violence, and worth.

Labor, Blackness, and women are a threesome, a relationship that lives and thrives from the plantation to the pandemic and beyond. This relationship means that a breakup comes with deep roots, a long history, and modern manifestations. The entangling among labor, value, and history is precisely what makes this an “intimate” revolution. And like all break-ups, it’s messy.

Black Women, Labor, and History

Labor. For Black women globally, this word carries weight, history, legacy. The language of whiteness made labor life, breath, and death in the systems of enslavement, colonialism, and apartheid that built—and continue to shape—our worlds. Your worth was measured in how much labor you could take on, how fast you could do it and with little to no rest. Do too little, and whiteness would kill you; do too much, and that labor under whiteness could kill you.

Historically, that labor was under the sun, the lash, the massa and the mistress. For you as an enslaved Black woman, a colonized one, or one navigating apartheid, labor was your calling. Whiteness worked you to death. Literally. And that work had multiple manifestations. Different women did different kinds of labor. Your body was capital, and then capitalized.

Labor as Connection to Value and Worth

What makes this history and its contemporary manifestations particularly enraging, confusing, and internalized is that there was always a parallel narrative of Black women as lazy. Back-breaking, soul-aching labor by Black women was rewritten as laziness, and the two stood cheek by jowl. This “lazy Black woman” narrative was part of the psychology of whiteness. What it did was nurture a connection between value and labor within Black women—part of the internalized racism. The narrative would develop an intersection with never wanting to be seen or considered as lazy, and taking on more labor to prove that you were not. You did more to prove you were worth more. Laziness historically was a death sentence. It came alive as emotional connection: your labor and your value were how you measured how you mattered.

That’s because how whiteness saw you, mattered.

This seeing by whiteness created a cycle of different kinds of violence: the economic intertwined with the emotional— the connection between the two. Understanding the combined toll of both must be part of this breakup, and requires scrutiny, identification, unraveling, and unlearning. This is how the language of whiteness thrives within Black women’s emotionality. This emotional connection to your value as historically defined by labor was about how much you do, how much more you can do, how much you have done, how much more you are willing to do, and how valuable you are because you do it. Enduring, exhausting, unending labor.

This connection then was about a conditioning that manifests not in the labor Black women do but in the relationship to that labor—one that took root in Black women’s minds and souls.

Black women’s labor globally was also in service of freedom, of holding agency over their own bodies and fighting tooth and nail for self-ownership and actualization. It matters that we honor and name that. Black women are the designated warriors—and worriers—about the state of the Black community. We are its caretakers, nurturers, service providers. We are its first responders. There is a beauty and a badassness to that role, one that we revel in and are rewarded by. There is power and progress because of that work. Black women are builders, believers. There is change because of that work. There is deep love in this too. When the arc of the world bends toward justice, it is because Black women are the arc.

But we are not bending. We are breaking.

Being the arc without sufficient support and without a strategy for rest and replenishment is part of the community labor landscape. That landscape must change for our individual health, communal health, and societal health, for a practice of liberation.

Historical Labor, Modern-Day Grind

Grind. That’s the contemporary manifestation of this historical relationship to labor birthed by the language of whiteness, and its legacy. Grind is not a word for Black women; it’s our Black mother tongue. It’s a culture, a generational inheritance passed down, passed around, and emerging from the bellies of Black women the world over. It is toil always, rest never, reward rarely. We grind for good, we grind for God, we grind for men. No healing lies there.

I call it push-through-o-nomics. Grind ignores every sign that your body, spirit, and mind cannot do any more, take any more, or move any more. It demands that you discard all those signs and push through—and find power and pleasure in pushing through, even after you have broken. Breaking is illegible, unacceptable, and makes you somehow less of a Black woman. It is familiar unrelenting exhaustion. Your heart aches, your soul is breaking, your health is failing; don’t stop . . . even if it’s killing you, if you’re burned out and burned up—but keep pushing, keep going, you must, you have to, keep going. Always, keep going.

Intimate revolution is not about prosecuting Black women’s agency, endurance, and sheer will and fight to survive. We are here because of that. But this is about Black women’s healing. So, it is not about toughness, it’s about toll. It is about the devastating toll on who we become as a result of the language of whiteness, the toll of unrelenting resistance, and this relationship with labor.

Unlearning is hard because this language of grind surrounds us—our mothers, grandmothers, our girls, our families, our communities, our men, the organizations for which and in which we work, in which we serve—but that do not always serve us—each and all of these communicate and demonstrate how grind is gangsta and glorious. It is expected and required.

To not battle through, to stop, to choose rest, and to privilege replenishment trigger deep feelings of guilt. Black women emotionally back-and-forth within themselves, questioning and then challenging our own feelings, talking ourselves out of them, guilting ourselves because of them. Often, perhaps eventually, we convince ourselves that we “deserve rest, dammit”; we even justify rest, but too often we’re unpersuaded by our own internal need and pushed by ancestral inheritance. We find ways to push through, and keep going.

This compartmentalization of Black women and their labor was about dehumanization. What we need now is to institutionalize wellness, rest, and replenishment for Black and Brown women.

This is about redefining Black women’s relationship to labor, and breaking up with the historical labor legacy that lingers, and threatens Black womens’ future.