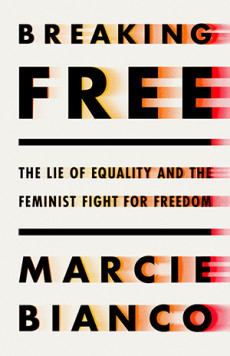

Breaking Free: The Lie of Equality and the Feminist Fight for Freedom

Marcie Bianco

336 page, PublicAffairs, 2023

Should equality be the strategy and endgame of the feminist movement? In Breaking Free, I argue that how equality is rendered in white supremacist cis-heteropatriarchal systems—how it takes shape and how we feel and experience equality—is anything but true equality. To free ourselves from equality, and from the equality mindset produced by the generations of social conditioning, I call for freedom to be the guiding ethic and politics of the feminist movement. A lifelong practice of self-creation based in accountability and care and that endeavors to build a freer and more just world, freedom is individually felt but collectively realized. Black feminists and freedom fighters like Audre Lorde have told us time and again: “I am not free while any woman is unfree, even when her shackles are very different from my own.” Or, as civil rights organizer Fannie Lou Hamer said in a 1971 speech, “You are not free whether you are white or Black, until I am free. Because no man is an island to himself.”

In short, the issues of our times and specifically the mounting and relentless attacks on our bodily autonomy, dignity, care, and justice are matters of freedom, not equality. In Breaking Free, I outline three freedom practices in direct response to the three primary forms of women’s oppression: of the mind, of the body, and of movement.

The following excerpt reflecting on Black Lives Matter as a social movement is drawn from the final chapter on the third practice on the freedom to move, both individually and collectively. In this chapter, I argue that liberation does not emerge from just any type of movement. It must be deliberate because our freedoms are interconnected and interdependent. As a freedom practice, movement must have intentionality. To live a considered life and to catalyze ethical social change, our movement—and movements—must be thoughtful actions or extensions of the self into the world.

The critical takeaway from this excerpt is that every individual has the choice to act, to take action; within the conditions specific to our lives, we have the choice not to be bystanders and to join movements. In the context of social sector work on movement building, we must understand that movement itself—even the “movement” entailed in intermediary work, or in the serving as a “connector” or “hub” at the heart of “cross-sector collaboration”—is the essential component to building movements.—Marcie Bianco

* * *

The freedom to move is about more than just individual mobility and access; it’s about the ability to create movements: deliberate, constructive actions that catalyze and generate new relationships, alliances, collaborations, and coalitions that can do the work of changing our institutions. The power of movements is based in the ideas that fuel them, that inspire people to come together and work toward the realization of a shared goal or values.

Even though freedom work begins with and within the self, we do not create the conditions for our freedom on our own. From collaborations to collectives, circles to communities, it is only by coming together and forming movements that our freedom work can achieve scale, transcending our individual efforts to effectively change our society and its institutions.

No one person can tear down the white supremacist cis-heteropatriarchy—because, if it were possible, a woman would’ve done it already. The fact is, we need each other. And we need to understand and learn from the past to break free from it. That means not only addressing the historic forms of oppression that have limited our accessibility and movement but also taking account of what has kept us—including ourselves, our own biases, and, within the feminist movement specifically, our racism, ableism, homophobia, and transphobia—from forming relationships and building a movement together.

Black Lives Matter

BLM illustrates the magnitude of a social movement’s transformative power to completely reframe and elevate nationwide conversations about racism, health inequities, disenfranchisement, and police violence, and how these issues are connected. The roots of the global movement are diverse and diffuse. The organizational name and brand were established in 2013 as an online platform by three seasoned organizers and activists—Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, and Opal Tometi.1 The activism at the heart of BLM, to be clear, extends beyond the formal organization and includes a global network foundation, nonprofit and for-profit organizations, an action fund, and a political action committee. The Black Lives Matter Global Network Foundation is just one of dozens of groups within the coalition of the Movement for Black Lives (M4BL), which first convened at a conference in 2015 at Cleveland State University to strategize and establish a policy platform. The scope of these multi-issue, multidirectional movements is what gives BLM and M4BL such potency in its unyielding commitment to the abolition of anti-Black and racist institutions, laws, policies, and social norms. This abolition effort, as the 2016 M4BL platform stated, is “to move towards a world in which the full humanity and dignity of all people is recognized.” The movement’s platform outlined six demands—including reparations, divestment in carceral institutions, and community control of laws and policies—for not just abolition but also the formation of Black political power and Black self-determination.

BLM ignited a profound and ongoing change in our society. It has changed the fabric of American culture and politics, changed the language we use to discuss police violence and systemic discrimination. It has transformed how we discuss American racism, and how we understand the foundations of this nation’s history as rooted in Indigenous genocide and African enslavement. It has forced even some of the most unwilling among us—those who have clung to “colorblindness” as a testament that they Are! Not! Racist!—to see racism, to bear witness to the horrors and terrorism inflicted upon Black people by the state and by its white citizens. BLM has become a force in our political landscape, and, through myriad grassroots and organizational efforts, has paved the way toward the abolition of the systems and institutions that perpetuate racism.

“Movements are the story of how we come together when we’ve come apart,” Garza wrote in The Purpose of Power. To be effective, she noted, movements require “sustained organizing” by “individuals, organizations, and institutions.” Organizations are the spaces where movements acquire their literal structure—where people come together to set an agenda and build relationships and communities—that sustains those movements over time.

Garza emphasized that “hashtags do not start movements—people do,” and, as a nod to the antiracist and feminist movements that have come before BLM, pointed out that “movements do not have official moments when they start and end, and there is never just one person who initiates them.”

Contrary to portrayals in popular entertainment, social movements are not made of one or five white guys but rather consist of a broad coalition of people. Organizational work is distinct from activism in structure, intention, and temporality; while types of the latter—from online petitions to street protests—are incorporated into the former. Despite the hero narratives depicted in movies and television, the actual work of social movements is done by dozens upon dozens, if not hundreds and thousands, of people, not just because their lives depend on it but because there exists a collective consciousness about the values of accountability, dignity, and care. Writer and activist Sarah Schulman uncovered what the quality of this consciousness was in her historical analysis, in Let the Record Show, of what inspired people to join ACT UP:

These were people who were unable to sit out a historic cataclysm. They were driven, by nature, by practice, or by some combination thereof, to defend people in trouble through standing with them. What ACT UPers had in common was that, regardless of demographic, they were a very specific type of person, necessary to historical paradigm shifts. In case of emergency, they were not bystanders.

To not be a bystander is to make a choice to act. Schulman’s observation underscores an important commonality threaded through all effective social movements: They include people who may not have personally experienced, say, homophobia or racism, but who know that for society to change they must speak up and do something. They must choose to intervene.

To not be a bystander is, in a sense, the definition of what it means to be a citizen: to choose to take part in the collective society, to hold oneself accountable to the public.

Movements are not singular occurrences. They cannot be narrowed down to one protest or letter-writing campaign or sit-in. They also are not random, temporary reactions to violence but deliberate, intentional, organized, and sustained efforts. The most transformative social movements, furthermore, are not those that fight for equality within the white supremacist patriarchy but those that seek to abolish oppressive systems, institutions, and traditions. These movements change us, change how we move, and change how we engage with and relate to each other in the world. These movements and their respective organizations, such as M4BL, ACT UP, and the Black Panthers, have been revolutionary because they sought to provide the care to their respective communities that society’s various systems—government, health care, and education—refused to provide them.

Movements vary in scope, shape, size, and mission. Yet, no matter the size or agenda, what singularly defines them is the fact that they begin with people, with collective mobilization. But they do not end there. Moms Demand Action, a nationwide grassroots movement of nearly ten million supporters whose mission is to change America’s gun culture and fight for federal gun legislation, began with Shannon Watts sharing her anger and frustration with government inaction in a post with her seventy-five Facebook friends after the Sandy Hook shooting in 2012.

“You should never underestimate a bunch of pissed-off moms,” Watts told Katie Couric in a March 2021 interview. The movement’s success has relied on its volunteers having conversations with their social networks online and offline, protesting gun violence in marches and public events, and even running for elected office—Lucy McBath and Marie Newman launched their political careers in the US Congress as Moms Demand members. In the 2022 US midterm elections, 140 Moms Demand volunteers supported by the movement’s newly formed political training program, “Demand a Seat,” were elected to office in states across America.