The Right Privatization: Why Private Firms in Public Initiatives Need Capable Governments

Sérgio G. Lazzarini

280 pages, Cambridge University Press, 2022

The public debate is rife with polarized views of how to deliver essential services such as education, health, and security. While some tout private innovation and operation as a way to supplant bad governments, others warn that private firms maximize profits at the expense of socially oriented service attributes. Many cross-sector collaborations, which arguably mix public and private objectives, have also been short-lived and insufficient to address pressing problems that require scalable solutions.

In reality, all forms of service delivery—public, private, and public-private collaborations—have merits and flaws. Private engagement can provide substantial benefits, but it is not a straightforward remedy to government failure and is not a way to get rid of bad governments. Rather, it requires the presence of capable governments units committing to well-defined policy objectives, mobilizing critical resources, and incentivizing effective and inclusive delivery.

In this excerpt from The Right Privatization: Why Private Firms in Public Initiatives Need Capable Governments, I build from case research to show how capable governments reject single solutions and experiment with plural paths of improvement, where public, private, and public-private forms of delivery coexist and learn from each other. Fostering government capabilities is thus a priority for policy makers and entrepreneurs seeking to increase the reach and impact of social innovations.—Sérgio G. Lazzarini

* * *

The acclaimed film director Francis Ford Coppola traveled to the city of Curitiba, Brazil, in 2003 to collect ideas for his movie project Megalopolis. He was interested in the string of urban innovations that Curitiba had implemented throughout the years and thought that those experiences could inform the plot of his planned movie, a futuristic tale about New York City reimagined as a utopian, citizen-centered urban collective.

Coppola was seen using public transport to visit multiple areas in the city, enjoying popular Brazilian dishes at local restaurants, interacting with people on the streets, and even helping a person wash a car.

A project that caught Coppola’s attention was Curitiba’s famed bus rapid transit (BRT). Launched in 1974, the initiative was a cheaper alternative to costly subway networks. The idea was to create dedicated street corridors for the transit of buses, with multiple stopping points built as tube-shaped stations and a system of prepaid tickets.

With this new system, passengers were able to reduce their travel time, while the BRT’s lower investment requirements—estimated as 20 to 50 times less expensive than other rapid transport options—allowed for a substantial expansion in coverage. The innovation was later adopted in several other countries and, in 2019, was selected as one of the top 50 worldwide projects of the past 50 years by the Project Management Institute.

During his visit, Coppola became friends with one of the leaders of the project, the architect Jaime Lerner, who served as mayor of Curitiba and then as governor of its state, Paraná. The private prisons mentioned in the Introduction to this book were another initiative implemented during his gubernatorial term. Coppola himself would appear in a documentary dedicated to Lerner, Uma história de sonhos (“A Story of Dreams”), which also recounts the creation of the BRT and the international recognition that followed.

The Curitiba BRT was one of the cases included in a comparative project that I undertook with Nobuiuki Ito and Leandro Pongeluppe to study the performance of public initiatives in Brazil, India, and South Africa. My research group collaborated with a global team of Accenture consultants (led by Armen Ovanessoff and Felippe Oliveira) to examine public service initiatives through a variety of measures of performance and organizational traits – including the mix of public and private actors involved in their design and execution.

We focused on four activities that have a large potential impact on the daily lives of citizens: education, transport, urban development, and bureaucratic services (such as units created to expedite the processing of documents or payments). For each country and activity, we then created matched pairs of projects with evidence of success and failure based on indicators of effectiveness.

Projects classified as successful had evidence of positive outcomes compared to what would be likely to have happened without the intervention (this is the counterfactual scenario discussed in the previous chapter). In contrast, cases of failure showed deficient execution and excessive costs; some of the projects were even aborted.

The Curitiba BRT, for instance, allowed for faster transit (a quality attribute) at lower cost. Unfortunately, we were unable to find detailed benefits—cost analyses for all projects, but we were able to identify multiple sources of information to help classify the cases. Although we focused on effectiveness, all successful cases tended to promote inclusions—such as cheap transportation, high-quality public education, or urban development in poor areas.

Using interviews with specialists involved in or familiar with each project, we then measured a host of variables that could explain the distinct outcomes we observed. We gauged the project’s degree of external engagement using a 1–5 scale, with the highest scores assigned to situations where for-profit and/or nonprofit organizations worked alongside personnel from the government unit in charge of the project and collaborated on various tasks such as project design, operation, and ancillary services.

In the case of the Curitiba BRT, manufacturers such as the Swedish multinational Volvo helped create new designs for buses with higher passenger capacity and improved stations. The operation of the lines subsequently involved private bus companies under concession contracts. Educational institutes provided additional technical support and training.

Yet Jaime Lerner and his team also marshaled valuable resources within the public bureaucracy. A central actor was the IPPUC (Institute of Urban Research and Planning of Curitiba), a municipal unit with a technical, multifunctional group of engineers, social scientists, and urban planners in charge of optimizing the transportation network. Project leaders had a clear vision of generating a faster and cheaper transport option, supported by competent processes of planning, communication, and monitoring.

All these factors suggest the presence of strong government capabilities, which we coded in the same way we did external engagement, based on interviews, to reflect the extent of mobilization to pursue well-defined goals, adoption of professional management practices, and use of accountability procedures to avoid corruption.

These capabilities, to be sure, were not uniform over time. In Curitiba, more recent administrations failed to continue optimizing the BRT system on a par with the increased level of traffic. The high-performance cases should be understood as projects that, at least for some time, were competently planned and executed, avoiding the wasting of public money and energy.

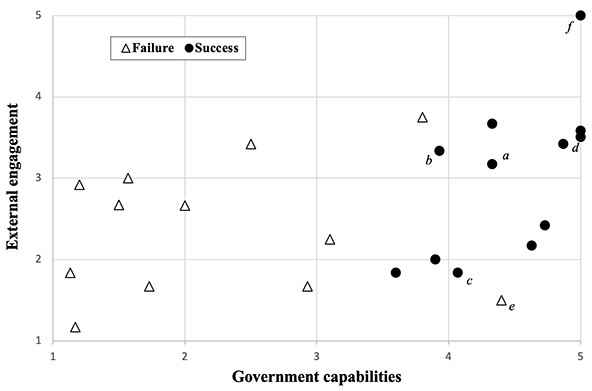

Figure 1 shows how the projects varied in terms of external engagement and government capabilities and how these factors are associated with their observed success or failure (high or low perceived effectiveness). Simple associations, it is worth remembering, do not reflect causation; throughout this chapter will present more robust evidence on the role of government capabilities. With this caveat in mind, we see that virtually all the successful projects we studied had above-average levels of government capabilities. As these capabilities increase towards the right side of the graph, we observe more successful cases with higher private engagement (the upper-right area), but we also see good projects that do not substantially rely on external actors (the lower-right area).

Figure 1: External engagement and government capabilities influencing the outcomes of public projects in Brazil, India, and South Africa

Note: Projects were classified as cases of success when there was evidence of positive outcomes to the target population and cases of failure when there was poor implementation and excessive costs. Thus, the classification reflects perceived project effectiveness. Government capabilities and external engagement were measured based on interviews using 1-5 scales. In particular, external engagement indicates whether for-profit or nonprofit firms deployed relevant resources to the design and implementation of the project. For more details on the sample and measures, see Lazzarini, Ito, Pongeluppe, Medeiros and Ovanessoff (“Public Capacity, Plural Forms of Collaboration, and the Performance of Public Initiatives: A Configurational Approach.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 2020). The letters indicate projects that are discussed in the text. a: Curitiba BRT system (transportation, Brazil); b: Hyderabad e-Seva (bureaucratic services, India); c: Hyderabad Metro Water Supply and Sewerage Board (urban development, India), d: Cape Town MyCiTi BRT System (transportation, South Africa); e: Program to improve learning and healthcare indicators for children (education, India); f: KwaZulu-Natal - Siyakha Nentsha (education, South Africa).

This pattern suggests that government capabilities were associated with not only project success but also higher private engagement. Yet an increase in government capabilities seemed to generate two paths to higher project effectiveness: either substantial public (in-house) execution or higher external engagement of for-profit or nonprofit actors.

Thus we see that capable governments not only tailor delivery forms to contextual conditions and implement adequate governance remedies (as discussed in the previous chapter), but also explore multiple—and sometimes concurrent—routes of improvement. For capable governments, “many roads lead to Rome.”