Despite unprecedented progress in poverty reduction over the last few decades, the scale of the challenges we face today is still daunting. Nearly one billion people lack electricity, over three billion lack clean water, and 750 million lack basic literacy skills. At the same time, many innovations to address these issues have already been invented: Technological innovation, such as microclimate predictors for farmers, and mobile money, now allow us to reach the last mile like never before, and there is a rich landscape of social enterprises solving the problems of poverty at local levels around the world.

Because very few of these solutions reach the necessary scale, we need to explicitly confront the obstacles hindering successful pilot projects and scale these innovations to tackle the full magnitude of the problem.

Scaling Up Development Impact draws from a decade of experience working with grassroots organizations. It recognizes that scaling up is a dynamic process of transformation, where best practices do not necessarily apply. It emphasizes that scaling requires putting the people closest to the problem at the center, understanding that they have the utmost knowledge of their problems and thus are invaluable in co-creating long-lasting, scalable solutions. It examines scaling up from the lens of navigating complex systems and highlights the role of continuous learning, iteration, and adaptation. The book offers a truly comprehensive understanding of scaling up in its various dimensions, delving into scaling through for-profit enterprises, governments, and social enterprises, including the crucial role of funders.

In Chapter 5, “Scaling through Government,” we discuss the promise and pitfalls of scaling via the government. The excerpt below showcases two of three cases of scaling innovations through government featured in the chapter: the scaling of women self-help groups in India and the scaling of an education model in Brazil.—Isabel Guerrero, Siddhant Gokhale & Jossie Fahsbender

* * *

Scaling projects, programs, and policies through government offers the greatest potential for development impact. Governments typically have a vast distribution network to reach the poor, unparalleled in size and reach, even relative to the largest private corporations. Moreover, governments command substantial budgets for social and economic services, making it a powerful player at scale with the capacity to replicate proven innovations. For all these compelling reasons, most social enterprises and other organizations looking for impact seek to work with the government to influence change at scale.

Unfortunately, scaling through governments is particularly challenging. Their slow-moving bureaucratic structures limit the efficient distribution of innovations to the last mile. Capability constraints, such as corruption, insufficient skills, and lack of personnel, hamper the effective implementation of services. Complex principal-agent problems also arise from the multiple goals of politicians, bureaucrats, and frontline service delivery agents; and the hurdles of implementation arise within a hierarchical state system. Another roadblock to scaling innovations through governments results from the lack of coordination between different government departments resulting in inertia and delays. Moreover, government structures of command and control, designed to avoid failures, make it difficult to innovate through an iterative process of trial and error. Finally, political cycles prioritize short-term wins to appeal to voters, potentially compromising the long-term investment in innovations needed to solve development problems.

One solution to resolving these tensions lies in adapting best practices from for-profit enterprises to allow for innovation within the government system. As we saw in the previous chapter, lessons from for-profits include: searching for a Minimum Viable Intervention that is simple, cost-effective, and easy to implement across different contexts; designing programs with the user at the center; tapping into the knowledge of the government employee at the last mile who is often overlooked despite being closest to the source of the problem; iterating to find a solution before scaling; and using agile methods for implementation. Learning from for-profit enterprises also includes emphasis on accountability, quality of service, efficiency, speed, and a less hierarchical structure than traditional bureaucratic systems.

In this chapter, we discuss how scaling up programs or projects within governments offer different challenges, especially relative to the private sector. We then offer examples of two different pathways to scale, one taking innovations developed in the private sector or social enterprises to the government for scale, and the other innovating within the government itself. Governments also play a crucial role in policymaking and influencing the regulatory environment. We reserve the discussion of the government’s role in managing the regulatory environments, especially for social enterprises, for Chapter 9.

Two Pathways to Scale Through Government

There are two pathways to scale through government. The first pathway involves the government leveraging its scale and distribution to replicate innovations initially developed by civil society or in the private sector. This is a useful pathway given the difficulty of creating spaces for innovation in government, especially when failure is politically costly. To illustrate this, we focus on women’s self-help groups in India, which began as an innovation to improve empowerment, developed by civil society organizations, and eventually became part of India’s most important poverty alleviation program today.

The second pathway is to innovate within the government; to illustrate this pathway we will discuss two examples. The first is a successful education reform in Sobral, Brazil, which shows the power of experimentation, iteration, and learning to achieve better learning outcomes. Sobral’s education model is currently being tested at the federal level in Brazil and has inspired education reforms in Pakistan and Kenya. The second example is Progresa/Oportunidades, a conditional cash transfer program in Mexico, which shows a more traditional approach to government innovation, with large-scale pilots, rigorous impact evaluations, and a gradual process of building political support and fiscal space. Oportunidades scaled to 5 million families in Mexico and survived four six-year presidential terms. It inspired conditional cash transfers all over Latin America and the developing world.

Taking Outside Innovations to Government

The National Rural Livelihood Mission (NRLM) in India: A 40-year Story

NRLM is a flagship poverty reduction program of the Ministry of Rural Development (MoRD) in India. The program organizes poor women into federations of self-help groups (SHGs) to increase their income and enhance economic empowerment. The roots of NRLM can be traced back to innovations that grassroots and civil society organizations developed over many decades that were eventually adapted and replicated by the government to reach over 80 million women.

The seeds of NRLM emerged from a wave of social mobilizations in the late 1960s and early 1970s, that started women’s community-based organizations with the formation of the Mysore Resettlement and Development Agency (MYRADA) and the Self-Employed Women’s Association (SEWA). By the 1980s, PRADAN, along with MYRADA, was working and experimenting with the first self-help groups that were remarkably similar in formation to the self-help groups today.1,2 These efforts were first supported by the government through a pilot program that linked these groups to banks through the National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD), thereby providing the early scaffolding and foundation for scale.

In the late 1990s, several initiatives to explore scaling this innovation emerged. One of them was a UNDP 3-year pilot for SHGs in South Asia.3 The project focused on BRAC in Bangladesh, Aga Khan Rural Support Program (AKRSP) in Pakistan, and Amul (a dairy cooperative) in India. The Pakistan component was designed for village development in remote areas where the state had never reached. In Bangladesh and in India the projects looked at the learnings from programs that had scaled. The pilots in India targeted small groups and provided substantial financing.

Also, in the later 1990s the rising prominence of SHGs caught the attention of the Ministry of Rural Development (MoRD) which had launched the Swarnajayanthi Gram Swarozgar Yojana (SGSY) that was aimed at enhancing self-employment and skill-development. By the early 2000s, the SHG linkage with banks, layered with skill development and training, expanded in state governments. This expansion was in part due to the proof of concept demonstrated by the UNDP pilot that paved the path for other states.

In the decade that followed, there was extensive experimentation with different models and adaptation to different realities as SHGs became central to state rural development programs. Andhra Pradesh was an early success. Several states followed the Andhra Pradesh model and, at this stage, the World Bank4 played an important role in promoting SHGs at the state level, assisting in financing and operationalizing the innovation. The Kerala state livelihood mission, built from within their civil society and village government movement, embraced SHGs in a different approach. Bihar, a state that was considered incapable and vulnerable with widespread poverty and rampant corruption, transformed the model to respond to their needs. This new model started with the government retiring high-cost debt and developing non-farm livelihoods; it has become a hugely successful program building on contextualized knowledge across the state.

Based on the success of several state livelihood programs, NRLM was established in June 2010 in a radical departure from previous rural development programs. NRLM was designed to become one of the key pillars of rural poverty reduction efforts in India, mobilizing all rural, poor households into SHGs and SHG federations providing access to credit and other technical and marketing services. With World Bank support, MoRD created a professional service delivery architecture based on the results of state-level rural livelihood projects. The national approach was also designed through a process of experimentation and adaptation, starting with ten high-poverty states to create a model for NRLM for future expansion.

Today, although much work remains to truly attain recognition, dignity, and independence for rural women, the National Rural Livelihoods Mission reaches approximately 83 million women. It is the largest livelihood program in the world, and it started from grassroots innovations that established the ‘proof of concept’ over a period of thirty years before the government was ready to scale it up at the state level first and then at the national level.

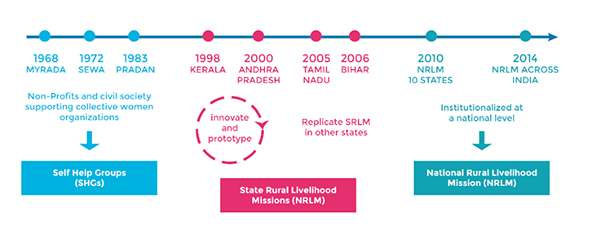

This first pathway to scale, whereby innovation is first developed outside the government, takes considerable experimentation and adaptation before it is ready to go to a national level. As we can see in Figure 5.1, women’s collectives and SHGs were tested for two decades before there was proof of concept that organizing women helped change behaviors and activate agency. The main manifestation of this change was in the ability of SHGs to save, tap into finance, and feel represented by village organizations and federations that could connect them to government programs.

Figure 5.1: The Phases of Scaling Up Self-Help Groups through Government

It is also clear from this illustration that the intermediation role is an important prerequisite for success in scaling through government. Several organizations, such as UNDP, played that role for SHGs in the transition to scale through states. Once the UNDP project showed proof of concept, it was necessary to have a few champions at the state level with the freedom to experiment and adapt to their own realities. Given the size and diversity of India, it is not surprising that the route to scale at a national level could only be feasible after many states had become champions of SHGs. Given India’s size and diversity, building trust and ownership state by state is the only way for programs to scale while maintaining sustainability.

Innovating and Scaling Through Government

The Strategic Triangle

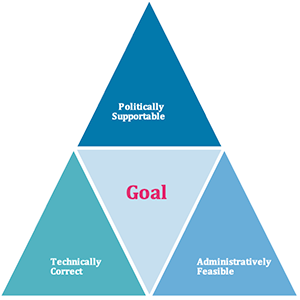

Working within the government introduces new layers of complexity that are not present in for-profit enterprises. A scalable policy, program, or intervention in a government context must meet the three criteria which are summarized in Figure 5.2: technical correctness (effectiveness), administrative feasibility (implementability), and political supportability (necessary buy-in). Many government projects, programs, and policies fail because they are lacking in one or more aspects of this trinity.

Technical correctness assesses whether an intervention works effectively in various challenging conditions, such as low-capacity settings, remote areas, and diverse regions within the country. It is often measured by impact evaluations. Administrative feasibility evaluates whether the intervention can be implemented by the state bureaucracy, considering the budget/cost constraints, capacity limitations (including assets, skills, and personnel), and existing regulations. Finally, political supportability ensures the necessary buy-in among key political actors and ensures the sustainability of the intervention for long-term impact. Too often, we see interventions that work and are even implementable but do not last because of changes in the political environment.

Figure 5.2: The Strategic Triangle of Effective Policy Design

Navigating the authorizing environment, especially within the government, can be challenging due to their fragmented and hierarchical natures, with multiple agents acting under various incentives. As we saw in Chapter 3 on systems, within a complex multi-stakeholder system we will find many breakage or leverage points. Engaging relevant stakeholders from the design phase helps identify interventions that are viable, legitimate, and relevant for the specific context.

The strategic triangle offers a useful framework to assess the scalability of interventions in government but also describes the unique challenges of working with governments. We now turn to the pathways to create scalable interventions within government with all three elements of the strategic triangle.

The Case of Sobral

The education reform in Sobral (Brazil) is an example of innovation within the government that has led to successful long-term results.5,6,7 Despite being in Ceará, one of the poorest states in the country, Sobral now has the best primary and lower secondary education in Brazil. Between 2005 to 2017, Sobral went from ranking 1,366 to being the best performer in the national index of quality of education. This change was possible thanks to a sustained education reform incorporating continuous learning and iteration while maintaining political support.

The impressive shift in learning outcomes is the result of a process that has required more than 20 years of effort. A diagnostic assessment in 2000 showed that only 62% of second-grade children could read.8 Municipal leaders realized that all the efforts to increase student enrollment were not leading to better learning outcomes and decided to set a clear goal for all students to be literate by the end of second grade. The literacy problem had several root causes: the school network was fragmented with too many small schools; children started literacy education too late; there was a lack of support for teachers and pedagogical materials were not effective; there were no incentives for teachers and directors to improve; and school management needed to be strengthened.9

Municipal leaders started by focusing on two short-term actions. To tackle the late start to literacy education, they passed a law to start primary education at age six instead of seven. This change was politically supportable and administratively feasible because it could be addressed through a municipal law. Parents and teachers were open to the change and the municipality had the economic and human resources to implement it. To solve the problem of having too many small rural schools, the next step was to consolidate the number of municipal schools from 96 small schools to 38 larger schools with better conditions. This change had political support from the government that had recognized the problem of multi-grade classrooms. However, parents did not welcome the change because of transportation challenges. The municipality created enough support to begin the reform by providing transportation for students and meeting with the community to obtain parents’ support.

Between 2001 and 2004, the municipality implemented reforms on four strategic levels: secretariat-level management, school management, pedagogy, and professional incentives. At the first level, they introduced external assessments and regular visits from the superintendent team, with indicators to monitor each school. On school management, they introduced technical selection criteria for the principals, gave more financial autonomy to the schools, and installed pedagogical coordinators in the schools. In pedagogy, they developed detailed literacy teaching materials, provided monthly training to teachers, and set monthly and weekly learning goals. Finally, they introduced the “Escola Alfabetizadora Prize” that gave monetary incentives to teachers, coordinators, and principals based on learning goals.

The use of data and regular feedback mechanisms were key to assess the technical correctness of the proposed interventions and to maintain political support from all stakeholders. The regular feedback mechanisms allowed them to reflect on the specific actions involving all local actors through weekly meetings between principals and pedagogical coordinators, periodic visits from the coordinators, weekly meetings between school principals, and bi-monthly visits from the school superintendent. During these meetings, they discussed challenges and lessons learned from implementing these new policies in the classroom. This was complemented by external assessments of students’ performance relative to the targets. Through this process, the municipality was able to provide timely data to sustain support from parents and schools and keep expanding support inside the government.

Sobral is a successful example of how to innovate within the government. It shows the level of complexity and the length of time required when scaling through government. Other states and countries have been inspired to replicate the success of Sobral. The program “Educar pra Valer”10 is taking the experience from Sobral to other municipalities in Brazil, starting from 5 in 2018 and expanding to 23 municipalities in 2019, across 12 states. Moreover, the current Minister of Education is scaling up Sobral’s reform to the Federal Level through the “Criança Alfabetizada” program.