(Illustration by Justin Renteria)

(Illustration by Justin Renteria)

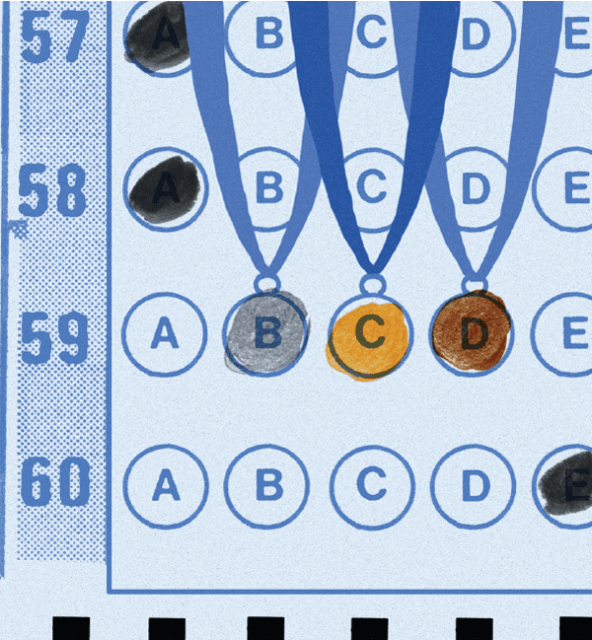

In 2009, the US Department of Education unveiled Race to the Top, a competition-based initiative that leveraged funding that Congress had appropriated as part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA). The goal of Race to the Top was to identify and invest in states that not only had outstanding ideas for improving educational outcomes but were also in a strong position to implement those ideas. The competition required each applicant to submit a comprehensive statewide plan for education reform. Underlying the initiative was a simple theory: By empowering states to lead the way, the federal government would elicit broadly applicable lessons on how to scale up effective policies and practices. As a result, more public schools would be able to provide an education that would prepare students for college and career success.

Race to the Top offers lessons in high-impact grantmaking that are applicable not only in education but also in other fields. The Department of Education runs about 150 competitions every year. But among those programs, Race to the Top stands out. It had more than $4 billion to allocate to competition winners, and it attracted the participation of nearly every state in the union. It arguably drove more change in education at the state, district, and school levels than any federal competition had previously been able to achieve. Partly in response to the initiative, 43 states have adopted more rigorous standards and replaced weak, fill-in-the-bubble tests with assessment tools that measure critical thinking, writing, and problem solving; 38 states have implemented teacher effectiveness policies; 35 states have strengthened laws that govern charter schools. In addition, new curriculum materials funded through Race to the Top and released in 2014 are already in use in 20 percent of classrooms nationwide.

Working with US Secretary of Education Arne Duncan, I led Race to the Top from its inception through 2010. At that point, we had awarded all of the grant money that was available under the program. I then served as chief of staff to the secretary through mid-2013, and during that period I remained involved in the program’s implementation. Today, six years after the launch of the initiative, we can start to place its achievements—and, in some cases, its missteps—in perspective.

Here are eight design principles, all drawn from our experience with Race to the Top, that are likely to apply to other high-impact policy initiatives.

Create a Real Competition

At the outset, we did not know whether the Race to the Top initiative would be compelling to state officials. The competition took place during a time of profound budgetary challenge for state governments, so the large pot of funding that we had to offer was a significant inducement for states to compete. But the appropriation for ARRA included nearly $100 billion for another program that benefited the education sector, the State Fiscal Stabilization Fund (SFSF). That sum dwarfed the allocation for Race to the Top. What’s more, every state automatically received SFSF funding on a pro-rata basis, whereas our program required states to write and submit detailed applications. When we began designing Race to the Top, we hoped that at least a dozen states would submit applications and expected that as many as 25 states would ultimately do so.

In the end, 46 states as well as the District of Columbia applied for Race to the Top support. A big factor in driving that high participation rate, I believe, was our decision to leverage the spirit of competition. We maximized the competitive nature of the program in three ways.

First, we decided that winners would have to clear a very high bar, that they would be few in number, and that they would receive large grants. (In most cases, the grants were for hundreds of millions of dollars.) In a more typical federal competition program, a large number of states would each win a share of the available funding. The government, in other words, would spread that money around in a politically astute way. But because our goal was to enable meaningful educational improvement, we adopted an approach that channeled substantial funding to the worthiest applicants.

Second, we kept politics out of the selection process. The secretary received numerous calls and letters from politicians who requested some form of special consideration for their states. In each case, the message from the secretary’s office was the same: “We’ll see what the expert reviewers say. The best plans will win.” In keeping with that commitment, we set up a peer-review process that relied on a panel of independent education experts. After the panel had scored each state’s application, we arranged all of the submitted plans by score in a state-blind way. We then funded the highest-scoring states.

Third, we placed governors at the center of the application process. In doing so, we empowered a group of stakeholders who have a highly competitive spirit and invited them to use their political capital to drive change. We drew governors to the competition by offering them a well-funded vehicle for altering the life trajectories of children in their states.

Some commentators criticized Race to the Top for promoting competition in a sector that, in their view, should be collaborative. But that is a false dichotomy. Collaboration is critical to designing strong solutions and implementing them well, and we provided incentives for collaboration in several ways. But we also capitalized on the power of competition to spark innovation and to spur applicants to stretch for goals that seem just out of reach.

Pursue Clear Goals (in a Flexible Way)

A central challenge in designing Race to the Top was to provide incentives for states to pursue a comprehensive reform plan while allowing them flexibility in how they approached that goal.

The competition required applicants to address four key areas: standards and assessments, teachers and leaders, data, and turning around low-performing schools. Previous reform efforts had often focused on a single “silver bullet” solution—only to fail when problems in related areas of the education system proved to be overwhelming. Race to the Top, by contrast, pushed each state to develop a coherent systemwide strategy for moving beyond the status quo. We also asked states to specify how their plan would target three groups that are especially in need of support: students from low-income families, students who needed to learn English as a second language, and students with disabilities.

Even as we were clear about the outcomes that Race to the Top sought to promote, we also encouraged states to devise plans that drew on their particular strengths and dealt with their particular challenges. In our scoring, for example, we aimed to provide enough clarity to ensure that applicants and reviewers would have a shared understanding of competition criteria. But we also encouraged reviewers to value, instead of penalizing, efforts by states to tailor their plans and timelines to match their particular capabilities and needs.

Our commitment to being systemic in scope and clear about expectations, yet also respectful of differences between states, was a key strength of the initiative. But it exposed points of vulnerability as well. In our push to be comprehensive, for instance, we ended up including more elements in the competition than most state agencies were able to address well. Although the outline of the competition was easy to explain, its final specifications were far from simple: States had to address 19 criteria, many of which included subcriteria. High-stakes policymaking is rife with pressures that bloat regulations. In hindsight, we know that we could have done a better job of formulating leaner, more focused rules.

On the whole, though, our approach led to positive results. In applying for Race to the Top, participating states developed a statewide blueprint for improving education—something that many of them had previously lacked. For many stakeholders, moreover, the process of participating in the creation of their state’s reform plan deepened their commitment to that plan. In fact, even many states that did not win the competition proceeded with the reform efforts that they had laid out in their application.

Drive Alignment Throughout the System

The overall goal of the competition was to promote approaches to education reform that would be coherent, systemic, and statewide. Pursuing that goal required officials at the state level to play a lead role in creating and implementing their state’s education agenda. And it required educators at the school and district levels to participate in that process, to support their state’s agenda, and then to implement that agenda faithfully.

In applying for Race to the Top, states developed a statewide blueprint for improving education—something that many of them had previously lacked

States control many of the main levers in education: They set educational content standards, commission standardized assessments, establish accountability systems, oversee teacher licensing, and provide substantial funding to schools. Historically, however, most state education agencies have focused less on playing a leadership role than on passing funds through to districts and monitoring regulatory compliance. Districts typically function as independent actors that report to their school board and interact very little with their state agency. With Race to the Top, we aimed to encourage states and districts to achieve alignment around a shared set of education policies and goals.

To meet that challenge, we required each participating district to execute a binding memorandum of understanding (MOU) with its state. This MOU codified the commitments that the district and the state made to each other. Reviewers judged each district’s depth of commitment by the specific terms and conditions in its MOU and by the number of signatories on that document. (Ideally, the superintendent, the school board president, and the leader of the union or teachers’ association in each district would all sign the MOU.)

The purpose of the MOU process was to generate serious conversations among state and local education officials about their state’s Race to the Top plan. The success of the process varied by state, but over time these MOUs—combined, in some cases, with states’ threats to withhold funding from districts—led to difficult but often productive engagement between state education agencies and local districts.

Encourage Broad Stakeholder Buy-In

To succeed, Race to the Top had to provide incentives for states to develop reform agendas that were not only bold enough to merit significant investment but also capable of gaining broad acceptance. Achieving that dual objective required the use of mechanisms that gave voice to many stakeholders while recognizing the central importance of a few. Our underlying goal was to enable each state to achieve an appropriate blend of executive leadership, union support, and community engagement.

Some critics claimed that Race to the Top gave unions veto power over state plans and that placing a premium on multi-stakeholder collaboration watered down reform efforts. Others argued that teachers had little or no voice in the program. These conflicting criticisms marked the line that we needed to navigate in designing the competition. To help each state bring all parties to the reform table, we deployed four tools.

First, we forced alignment among the top three education leaders in each participating state—the governor, the chief state school officer, and the president of the state board of education—by requiring each of them to sign their state’s Race to the Top application. In doing so, they attested that their office fully supported the state’s reform proposal.

Second, we requested (but did not require) the inclusion of signatures by three district officials—the superintendent, the school board president, and the leader of the relevant teachers’ union or teachers’ association—on each district-level MOU. This approach, among other benefits, gave unions standing in the application process without giving them veto power over it.

Third, we created tangible incentives for states to gain a wide base of community support for their plans. Securing buy-in from multiple stakeholders—business groups, parents’ groups, community organizations, and foundations, for example—earned points for a state’s application. Having the support of a state’s teachers’ union earned additional points.

Fourth, as part of the judging process, we required officials from each state that reached the finalist stage to meet in-person with reviewers to present their proposals and answer reviewers’ questions. At this meeting, a team that often included the state’s governor—as well as union leaders, district officials, and the state’s education chief—made its case to reviewers. We imposed this requirement largely to verify that those in charge of implementing their state’s plan were knowledgeable about the plan and fully committed to it. (This was particularly critical in cases where states had used consultants to help draft their application.)

Promote Change from the Start

One of the most surprising achievements of Race to the Top was its ability to drive significant change before the department awarded a single dollar to applicants. States changed laws related to education policy. They adopted new education standards. They joined national assessment consortia. Three design features spurred this kind of upfront change.

First, we imposed an eligibility requirement. A state could not enter the competition if it had laws on the books that prohibited linking the evaluation of teachers and principals to the performance of their students. Several states changed their laws in order to earn the right to compete.

Second, we decided to award points for accomplishments that occurred before a state had submitted its application. In designing the competition, we created two types of criteria for states to address. State Reform Conditions criteria applied to actions that a state had completed before filing its application. Reform Plan criteria, by contrast, pertained to steps that a state would take if it won the competition.

The State Reform Conditions criteria accounted for about half of all points that the competition would award. Our goal was to encourage each state to review its legal infrastructure for education and to rationalize that structure in a way that supported its new education agenda. Some states handled this task well; others simply added patches to their existing laws. To our surprise, meanwhile, many states also changed laws to help meet criteria related to their reform plan. To strengthen their credibility with reviewers, for example, some states updated their statutes regarding teacher and principal evaluation.

Third, we divided the competition into two phases. States that were unsuccessful in Phase One had an opportunity to strengthen their applications by making legal or policy changes in advance of applying for Phase Two. In the first phase, only 2 states made it over the high bar that we had set. In the second phase, 10 other states cleared the bar. The latter group of states had the benefit of learning both from reviewers’ comments and from the proposals of successful Phase One applicants.

Enable Transparency

From its earliest days, Race to the Top received a high degree of scrutiny and faced pressure to be above reproach. We decided that the best way to handle this pressure was to allow the public to see what we were doing. We followed a simple rule: If a document would be subject to public release under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), then we would make it publicly available even before we received a FOIA request. In that spirit, we placed every significant document on the Department of Education website at the earliest possible moment. Such documents included regulations related to the competition, guidance materials provided to reviewers, support materials provided to applicants, answers to applicants’ questions, each state’s application, video recordings of each finalist state’s in-person presentation, and reviewers’ score sheets and comments about each application.

The task of reviewing all of this material (and redacting personally identifiable information from it) placed a high burden on the department. Yet our commitment to transparency brought several beneficial consequences that we had not foreseen.

First, the quality of everyone’s work product was high because all parties knew that their work would be subject to public scrutiny. The department’s support materials were easy to follow; state applications were thorough and well written; reviewers’ comments were helpful and clear.

Second, participants developed a common vocabulary for talking about education reform and a shared understanding of what “high-quality” reform efforts look like.

Third, the Race to the Top website became a marketplace for sharing ideas. At the conclusion of Phase One, for example, participants began poring over one another’s applications to find out how other states had dealt with specific problems. As a result, ideas traveled quickly around the country.

Fourth, a “crowdsourced” approach to handling Race to the Top information emerged. We couldn’t keep up with the enormous load of data that the competition generated—and we learned that we didn’t have to. The public did it for us. State and local watchdogs kept their leaders honest by reviewing and publicly critiquing applications. Education experts provided analyses of competition data. And researchers will be mining this trove of information for years to come.

Build a Climate of Support

Providing support to states as they developed their application was crucial to the success of Race to the Top. Most states had been acculturated through previous Department of Education interactions to respond to departmental programs in compliance-oriented ways. The following question, asked in various ways by officials at applicant support sessions, exemplified the prevailing mindset: “If I do X, will I get full points? Or should I do Y instead?” Over and over, we replied, “There is no ‘right answer.’ You have to do what’s best for your state and then explain why it’s best.”

Three factors helped applicants meet the challenge of entering the competition.

First, stakeholders across the country mobilized to provide support to states. Experts developed roadmaps for applicants to follow. Foundations offered both human and financial capital. Business leaders helped guide strategic planning processes for many states.

Second, we designed the application process in the form of a step-by-step guide that anticipated the problems that states might encounter in formulating their reform initiatives. In particular, we organized the application around a series of questions regarding a state’s theory of action, its track record and its current capacity, its goals for reform, and its detailed plans for attaining those goals.

Third, we engaged in extensive outreach to applicants. We hosted webinars and held all-day in-person sessions in which we walked state officials through each item on the application. We also created a rapid-response system for answering questions that came in from states. Cross-functional teams—teams that included policymakers, lawyers, budget analysts, and program officers, among others—logged and tracked—inquiries and worked to answer them quickly, accurately, and in plain English.

Ensure Accountability

The investment that the department made in supporting applicants, coupled with the investments that states made in developing applications, reflected a sense of urgency that contributed to the success of Race to the Top. Yet the competitive nature of the program inspired some applicants to over-promise and underdeliver. To mitigate over-commitment, we adopted three strategies.

First, we asked applicants to set targets that were “ambitious yet achievable.” The mandate to combine those two qualities, we hoped, would result in a productive tension and lead applicants to strike the right balance.

Second, we asked applicants to submit evidence to support their claims. For some criteria, we required very specific forms of evidence. In other cases, the provision of evidence was optional.

Third, we required each state’s attorney general to sign a statement that attested to the accuracy of any information in his or her state’s application that pertained to state law. Race to the Top reviewers were in no position to interpret state law, so it was critical to have this check on the accuracy of applicants’ claims.

None of these approaches was sufficient to rein in the inclination of applicants to over-promise. Changes to certain federal rules would help solve this problem. Agencies should be able to set aside adequate funding to conduct peer-review processes, and they should receive broad leeway in managing those processes. That way, agencies would have the resources that they need to retain strong reviewers and to undertake thorough reviews of applicants’ implementation capacity. In addition, agencies should have the ability—without going through a years-long appeals process—to withhold or withdraw funds from grantees that fail to implement their plans. As long as the threat of losing funds remains weak, applicants will have an incentive to exaggerate first and beg for forgiveness later.

Competitions are an imperfect way to drive change. Yet as our experience with Race to the Top shows, they can serve as a crucible of reform for forward-thinking leaders. A well-designed competition can spur innovation, create a marketplace for new ideas, engage multiple stakeholders in a broad-based reform effort, and create conditions in which rapid change is possible—even in a traditionally change-resistant field. We will not know the full impact of Race to the Top for several more years. Already, though, it has provided important lessons for policymakers.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Joanne Weiss.