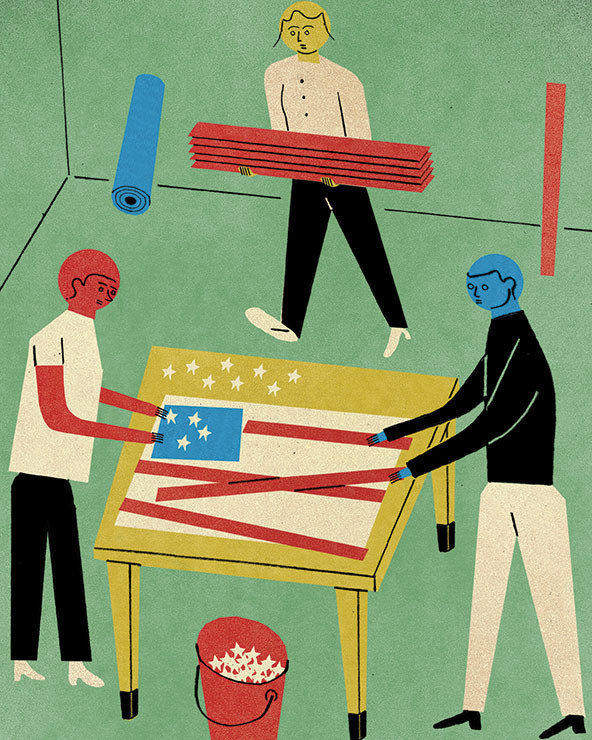

(Illustration by David Plunkert)

(Illustration by David Plunkert)

As a Black girl growing up in a segregated St. Louis, Missouri, in the 1950s and early ’60s, I adopted the prevailing story about our country. Nobody ever sat me down and laid it out. Rather, it was conveyed in school, on television, and in the movies. It was in the air. Neither did my family, teachers, or friends refute the story. It was the tale of a nation carved by ruggedness, exploration, and aspiration. A nation full of potential that could be tapped through individual grit and courageous efforts pushing society toward equality and justice.

For centuries, this story fueled aspirations for a better future, catalyzing the imaginations of Americans who fought epic political battles, from slavery abolition to women’s suffrage, to civil rights, disability rights, and LGBTQ rights. But, by the time I finished Howard University and became active in the Black Power movement in the late 1960s, I had recognized the story of America was largely a myth—one that relied on burying histories of Native American genocide and stolen land, the brutality of enslavement, racial violence, and discrimination against people of color.

Ultimately, the myth shattered under the weight of skyrocketing inequality, stalled economic mobility, institutional dysfunction, and greater public awareness of the nation’s fraught racial history and systemic racism. The story’s central promise and premise—opportunity for all—not only remains unfulfilled for people of color but also has become bitterly elusive for a large swath of the white population. Many white people, furthermore, do not believe the nation can provide good jobs, high-quality education, and economic security to everyone without taking away the advantages that they believe to be their birthright. And many people of color question whether the United States will ever enable all people to participate fully, prosper, and reach their full potential in society.

In some ways, it is encouraging that this whitewashed tale is no longer accepted as truth. Despite this sea change, a sizable minority of Americans has defended the myth, ushering forth a story of white grievance and nostalgia in an attempt to recuperate the past—to, as some say, “Make America Great Again.” They are willing to sacrifice democracy on the altar of racial superiority, as dramatically evinced by the violent insurrection at the US Capitol to overturn the 2020 presidential election. We also see this effort in laws and policies aimed at preventing Black, Indigenous, and racially marginalized people from voting and challenging the legitimacy of their ballots. And we see it in the well-orchestrated campaign to outlaw teaching schoolchildren anything about the nation’s racial history—because what is more threatening to authoritarian leaders than an educated, informed citizenry?

These are attacks not only on American democracy but more pointedly on the movement to build a thriving multiracial democracy. The timing of this backlash is no coincidence. People of color will be the nation’s majority by 2045, and, according to a 2019 Pew Research Center survey, a majority of Black, Hispanic, and white Americans agree that racial and ethnic diversity is “very good” for the United States. People of all races, ages, and backgrounds flooded the streets to demand racial justice after the murder of George Floyd in May 2020. This helped to secure groundbreaking commitments from the White House and corporations to advance racial equity. Voters have flocked to the polls in historic numbers to beat back antidemocratic candidates in 2020 and 2022. Countless activists, grassroots leaders, and public officials have redoubled their efforts to protect civil rights, strengthen communities, and remake the systems and institutions that have harmed and failed so many. Collectively, these efforts reflect a broader movement that is fighting against racist rhetoric and policies that trample civil rights.

To meet this inflection point, America needs a new story to energize the movement to build a sustainable, thriving multiracial democracy. In what follows, I describe the essential elements of that story, the most crucial of which is establishing the framework around race and racism without which we can neither decipher the root causes of the enduring and systemic challenges nor develop effective, equitable solutions. Right-wing politicians and media have thoroughly demonized discussions of race to prevent repair work and social change. And many white “allies” worry that focusing on race threatens their big-tent strategy. But this silencing tactic can no longer hide the fact that the systems and institutions designed to oppress Black people—an unfairly stacked economy, severe underinvestment in public schools, inadequate health care, and hollow support services—are now hurting all but the most affluent of Americans.

This new story also must dispel the canard that equity is a zero-sum game, and, above all, it must provide models of multiracial democratic action. Activists, organizers, leaders, and diverse coalitions and movements are demonstrating the power of solidarity and exposing the lie that talking honestly about race divides us. Talking about race is in fact the only way democracy can succeed in a multiracial society. And if activists and organizations are successful, building and sustaining a vibrant multiracial democracy will be the next great US innovation.

The Black-White Paradigm

The framework for understanding the nation’s racial history is what I call the Black-White paradigm: the composite of the economic, legal, institutional, social, and psychological structures forged from slavery that have systemized and codified oppression in the United States. As a lens through which to understand the nation’s history, this paradigm does not ignore or minimize the suffering and exclusion of others. Rather, it illuminates the interconnectedness of all people who have experienced racial violence, bigotry, and limited opportunity, and it exposes the biases and beliefs at the root of oppression. In the United States, the mechanisms that have shaped and perpetuated anti-Black racism have informed the oppressions of all marginalized groups.

The Black-White paradigm is predicated on understanding that history is alive, functional, and present in every aspect of our lives. History “does not refer merely, or even principally, to the past,” James Baldwin observed. “On the contrary the great force of history comes from the fact that we carry it within us, are unconsciously controlled by it in many ways, and history is literally present in all we do.”

In the United States, the history we carry begins with the genocide of Indigenous peoples—the theft of land, forced removals, and ongoing cultural erasure. These actions created the contours of racial violence and theft—of land, labor, family bonds, sacred traditions, agency, self-determination, and freedom. The vicious treatment of Indigenous peoples were the first expressions of the nation’s unwritten yet preeminent foundational belief that nonwhite people have less human worth and that they can be killed, shackled, exploited, and/or discarded to enrich those deemed to matter more. Anti-Indigenous violence was central to the creation of the structures of white supremacy, and anti-Black racism created the protocols of oppression now used to exploit and dehumanize all people.

The belief in a hierarchy of human value that placed white people—specifically wealthy white men—on top, gave justification to two and a half centuries of chattel slavery. An accurate history of the United States, therefore, must include the unimaginable brutality of that system, the economic contributions of the estimated 10 million Africans and African Americans held in bondage, and the stories of their indomitable resilience and resounding innovation. It also must include the brief promise of Reconstruction, when the United States first enacted policies to achieve a multiracial democracy. And it must include the Compromise of 1877, the deal that resolved a disputed presidential election in part by ending Reconstruction, which opened the door to Jim Crow racial segregation, sharecropping, chain gangs, and white racial terrorism.

The consequences of this compromise pushed Black people back into servitude and drove the Black exodus from the rural South to the urban North. With the Black-White paradigm as our framework, our new story must take account of the neglect, divestment, and wealth-stripping of Black people and communities through policies such as redlining—which prevented Black people from buying homes because they couldn’t obtain government-backed loans—and urban renewal programs that razed Black urban neighborhoods, displacing and impoverishing countless residents and businesses. Policies like these cemented vast racial gaps in income and wealth. So too did the destruction of families and communities of color through welfare, education, and health policies, including President Richard Nixon’s “war on drugs” and President Bill Clinton’s 1994 crime bill, which intensified the school-to-prison pipeline for Black and Brown youth. All these policies were predicated on false images and stereotypes of Black people and reinforced the marginalization of Black communities. Over time, these actions defined the terms of economic control, exploitation, geographic-based inequality, and ineffective social policy that have collectively enforced the protocols of oppression.

These protocols reverberate far beyond the Black community. For example, if the United States had addressed the crack cocaine devastation of Black communities in the 1990s as a public-health problem and invested in social supports—rather than criminalizing addiction, building more prisons, and incarcerating Black people en masse—the country would have been better prepared to respond to the opioid crisis that has ravaged many lower-income communities, including white ones. Similarly, if once ample investments in urban public schools hadn’t evaporated amid increased Black student enrollment, public education systems would not serve students as poorly as they do today. Also, cities would not have vast areas of neglect if white flight had not been the predominant response to legal requirements, ushered forth by Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, to racially integrate public schools.

The protocols of anti-Black oppression bred the racialization of immigrants and set the outlines of xenophobia that have shaped the US immigration system. They were founded in the legalized exclusion and subordination of migrant workers from Asia and Latin America that happened in the 19th and 20th centuries. They currently materialize in the ongoing terrorism, separation, and expulsion of Latinx workers and families who live in the United States, contribute to the economy, and pay taxes but remain undocumented and are denied a path to citizenship. They also appear in the recent violence and humiliation of Latin American families attempting entry at the Southern border.

The protocols of oppression, furthermore, play out in the criminalization and use of pseudoscience directed at transgender, nonbinary, and gender-nonconforming people; the hate and discrimination aimed at Muslims; and the violence and scapegoating of Asian Americans during the COVID-19 pandemic. In fact, COVID-19 would not have been as devastating as it was if the United States had not systemically neglected the health of Black Americans for centuries. This neglect translated into the disarray of public-health systems, rendering them unable to provide services the public needed and making Black, Latinx, and Native American communities more vulnerable to greater rates of sickness and death. Finally, the protocols of oppression take effect when marginalized people comply with and even endorse oppressive frameworks to gain access to power and privilege. This impulse to accommodate and be proximate to power is evident today—take, for example, the Black police officer who pinned down George Floyd and the Asian American police officer who prevented bystanders from intervening as a white officer knelt on Floyd’s neck for more than nine minutes.

Systemic racism was also realized in the extraordinary investments in white communities through large-scale government policies and programs. The 1956 Federal-Aid Highway Act gave emerging, predominantly white suburbs easy access to jobs and amenities in cities, increasing the appeal and financial value of suburban homes and communities, while breaking apart and displacing with highways urban neighborhoods of color. Too many white people remember the prosperity and opportunity of the mid-20th century without recognizing the outsize, discriminatory role played by the government.

This historical amnesia serves the interests of the people most intent on holding on to power and the structures built upon white supremacy. It is not surprising that these people have mounted an attack against educating children about the nation’s history. Suppressing racial history allows right-wing politicians and their sympathizers to insist that persistent inequalities are the result of the failings of Black, Indigenous, and racially marginalized people—not the consequence of past and present racial discrimination and the selective generosity of government-based investments that uplifted white people for generations. This amnesia obscures the essential role of massive government investments to create the large-scale opportunity that is needed now for the emerging majority.

Withholding racial history also erases the story of Black struggle and the role that Black Americans have played as democracy’s defenders. It obscures the ways in which people joined across race, ethnicity, and class and through collective action and achieved once unthinkable changes that made the country more just and inclusive—from universal suffrage to the end of legal segregation. Movement toward a multiracial democracy has always included millions of white Americans aligning themselves with communities of color and pushing for equity and inclusion. Again, it’s no wonder that an antidemocratic movement wants Americans to forget, or never learn, that cross-racial solidarity has been an essential part of democratic advancement and a source of power for marginalized groups.

People of color have the same demands and desires as the waves of immigrants from Europe through the centuries and white working-class people today: safe neighborhoods, wages that can support a family, high-quality education, and decent, affordable housing. Only by learning about and accepting the complexity of US racial history can we create a society that serves the needs of everyone.

Equity for All

There is an ingrained societal suspicion that supporting one group hurts another. Rooted in false notions of scarcity, this zero-sum thinking is embedded in our economic system, but it’s also been socially conditioned into us. In fact, when the nation targets support where it is needed most—when our policies and investments create the circumstances that allow those who have been left behind to participate and contribute fully—all of society benefits.

I first wrote about this idea in “The Curb-Cut Effect,” which showed how laws and programs designed to benefit vulnerable groups—like the sloped cutaways in curbs to assist people in wheelchairs—often benefit everyone. The example makes clear the broad social benefits that flow when policies and investments expand beyond zero-sum thinking and use equity to drive social- and political-change efforts.

Equity is no longer just a small idea or sidebar pilot program but has been adopted by public, private, civic, social, and corporate institutions. Acknowledging the fundamental importance of equity to the nation’s future, President Joe Biden’s first executive order in office announced an ambitious agenda that made racial equity the responsibility of the entire federal government.

The private sector also has shown an increased commitment to equity. While B Corporations remain a small portion of the private sector, they provide new models for corporate economic structures that serve beyond narrow profit-driven shareholder interests. For example, frozen-food manufacturer Rhino Foods developed an income-advance program that provides same-day emergency loans that transition into savings accounts for employees. Tile manufacturer Fireclay Tile created an employee-ownership model to democratize ownership and distribute wealth more equitably within the company.

Global corporations, too, are catching on to equity—not simply as performative social statements or philanthropic efforts but as necessary investments in their financial future. Big banks have a long history of racial exclusion and exploitation, from the use of redlined maps created by the federal Home Owners’ Loan Corporation in the 1930s to recent allegations that Wells Fargo used racist algorithms derived from past lending practices to reject more than half of the mortgage refinancing applications submitted by Black borrowers in 2020. However, some big banks have started to understand how shifting demographics will impact their economic future. After all, it is people of color who will fuel momentum to buy homes, start businesses, and send children to college. For example, to help advance economic growth, JPMorgan Chase has committed to invest $30 billion in Black and Latinx communities by the end of 2025, and Bank of America has committed $1.25 billion. Citibank not only has committed $1 billion but also was the first Wall Street bank to agree to a racial audit of its investment practices. Big corporations are slowly realizing that they will have no financial future if they don’t begin to provide equitable financial opportunities to those they have systematically discriminated against in the past.

Equity guides politics and policies back to what really matters—people. The too common refrain that maligns government as the problem overlooks how often big government actions are the solution to large-scale social challenges. When the COVID-19 pandemic forced millions of Americans out of work and threatened a near collapse of our economy, the federal government stepped up and, for the first time in generations, invested big and targeted the people who were hurting most: the 140 million Americans who are poor or low-income, and who include more than half of all children under 18, 42 percent of the elderly, 59 percent of Native peoples, 60 percent of Black people, 64 percent of Latinx people, and a third of all white people.

The six COVID-19 relief bills passed in 2020 and 2021 provided an estimated $5.1 trillion in relief funding to everyday Americans, which helped shore up consumer demand and dropped the unemployment rate by nearly 12 percentage points from its peak of 14.8 percent in 2020, ensuring the pandemic-related recession was the shortest on record. The expanded child tax credit that was part of the 2021 American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) closed a loophole that had prevented a majority of Black and Latinx children from benefiting from the tax credit and cut childhood poverty by 30 percent in the first six months of its implementation. The Center on Poverty and Social Policy at Columbia University projected that had the package of expansions in ARPA remained in effect for all of 2021, they would have cut childhood poverty by more than half, slashing poverty rates for Black children by 55 percent and for Latinx children by 53 percent.

Decades of research have demonstrated that people, families, and communities grow stronger when they have basic economic security. More recent research has shown that when programs put cash directly into the hands of people living in poverty, they spend it in ways that boost the economy. The Center for Guaranteed Income Research study on the Stockton Economic Empowerment Demonstration (SEED) guaranteed-income program found that most participant purchases were for basic necessities. The top three spending categories were food (37 percent), home goods (23 percent), and utilities (11 percent). Researchers also found the monthly stipend helped contribute to full-time employment and that SEED recipients showed enhanced well-being, as well as less anxiety and depression.

Despite the mainstreaming of equity, we are living in one of the most inequitable eras of the US economy. The inequity in our economic structures has created massive concentrations of private wealth, which threaten the nation’s long-term economic security. A new story must make clear that a multiracial democracy cannot flourish without a just economy. As people of color gain more political and economic clout, we should expect to see more public and private movement toward economic equity. This, too, will prove beneficial to society broadly.

A More Perfect Union

Ultimately, the galvanizing force of a new national story will lie in its vision of the future. It is the easiest part of the story to tell, because we need only to look at dynamic equity-driven movements and their leaders for a vision of a true multiracial democracy. They recognize that our fundamental liberties become stronger when our institutions are responsive to everyone—that when all people are served by our democratic institutions, all have a stake in protecting them. Collectively, these movements have the potential to show that a government of the people, by the people, and for the people can produce extraordinary, equitable results, but only if all the people really have a voice. Multiracial coalitions are working to remove barriers that block millions of people from opportunity and participation. They practice transformative solidarity—embracing one another’s issues and campaigns as essential for realizing a just society. Equity-focused leaders are the heirs to the best of America’s ideals. They have the radical imagination to conceive a nation united not by race, religion, ethnicity, or ancestral homeland, but by shared ideals of liberty, equality, and the pursuit of happiness for all.

These champions for a just and equitable future are translating the epic possibilities and dangers of this moment into political power, policy innovation, economic transformation, and cultural change. They know the framers of American democracy never intended to include people like them in representative governance. Yet the framers articulated the big ideas of our American democracy, which, if applied faithfully to all people, create the possibility of amazing change. In that way, the framers punched above their moral weight. Now, racially diverse leaders are breathing life and justice into principles that have been mere words until this point. The generosity of their vision is pushing the nation to deliver on the ideals that are enshrined in its foundational documents but have yet to be realized.

Today’s leadership carries the legacy of earlier generations who struggled to move the country closer to fulfilling its ideals. The civil rights movement demonstrated the catalytic, moral power of mass protest. It created a model for multiracial, multifaith organizing and alliances. Civil rights leaders such as Fannie Lou Hamer and Bayard Rustin underscored the need to make full use of the strengths of everyone. White people committed to racial justice joined the movement, at times sacrificing their lives. Crucially, the civil rights movement highlighted the central role of Black leadership in an authentic, broad-based struggle for justice, inclusion, liberty, and self-determination. As Harvard political theorist Danielle Allen has observed, there is a deep vein of thought in African American tradition and political philosophy about the meaning and value of freedom. Those who have been deprived of freedom understand its essence and import with crystal clarity.

Where civil rights leadership courageously demanded that the white-majority nation let Black people into its systems and institutions, today’s equity-focused leaders claim the nation and its future as their own. Rather than concentrate exclusively on greater legal rights and protections—which often do not fundamentally alter existing power structures—and rather than seek inclusion in and fairer treatment by institutions that were built on racial oppression, today’s leaders are claiming ownership over the construction of the next iteration of the nation. Many have moved beyond protest alone—important as it is—to build power and exercise ownership over all realms of public life. They are translating the energy of movements into organizations, which can represent the durability and power of the work and sustain long-term action to build a robust multiracial democracy.

A clear example is Gen Z’s extraordinary collective action and political engagement. After the mass shooting at Parkland High School, Gen Z activists created March for Our Lives, which fights for gun legislation. Its organizing director, Maxwell Frost, just became the first member of Gen Z elected to Congress. Gen Z also created the Sunrise Movement, a national political-action organization directly engaged in policy advocacy for climate justice. Recognizing the large number of organizations spreading dangerous disinformation to young people, Santiago Mayer, a Gen Z Mexican immigrant, created the pro-democracy organization Voters of Tomorrow, which helps young people become civically engaged. Gen Z’er and Diné activist Allie Young founded Protect the Sacred, which organizes the next generation of Indigenous leaders and helped President Biden secure victory in 2020 in Arizona, where the increase in Native American turnout was greater than the number of votes Biden won the state by.

Another example comes from the movement work to increase political engagement and voter turnout among Black communities and other historically marginalized communities across the South. For example, New Georgia Project and its former chief executive officer, Nsé Ufot, know it has never been more urgent to engage voters with a positive vision of a multiracial future, and to convince voters of color, Black voters especially, that their ballots make a difference. So the group is organizing Georgia’s growing communities of color to build a new electoral majority in the state, one that serves all its residents. In a region that has made it exceptionally difficult to vote, Ufot and her colleagues have leveraged technology to overcome suffrage barriers, trained homegrown organizers who have registered hundreds of thousands of voters, and built a multiracial coalition that achieved historic, decisive voter turnouts in 2020, 2021, and 2022.

A vibrant multiracial democracy depends on an equitable economy. Groups like Fight for $15, One Fair Wage, and the National Domestic Workers Alliance are organizing workers, mobilizing voters, and demanding policy changes to improve the employment conditions and the economic security of millions of low-wage service and care workers. Fight for $15 intentionally built a cross-racial movement and has won minimum-wage increases for more than 26 million people, fighting to reverse the nearly 50-year trend of stagnant wages for the lowest-paid workers, regardless of race. In 2022, One Fair Wage launched a national campaign to move state and federal legislation to raise wages and end subminimum wages in 25 states by 2026. The National Domestic Workers Alliance has amassed a data set with more than 200,000 Spanish-speaking care workers, providing a comprehensive picture of how many vulnerable care workers continue to struggle even as the pandemic recedes.

The equitable economy work of movement organizations is bolstered by strong research and academic support. Roosevelt Institute CEO Felicia Wong has analyzed the failures of neoliberalism, challenging “free-market” progressives. She has pointed out the contradictions inherent in an ideology that professes to value justice, inclusion, and the common good yet sanctifies unbridled capitalism, which has funneled massive wealth to the top while hollowing the middle class and consigning a third of the US population to live in poverty. Wong’s work provides an important intellectual critique of contemporary neoliberal policies and lays the foundation for building an economy that serves all.

Darrick Hamilton, a professor of economics and urban policy and the founding director of the New School’s Institute on Race, Power and Political Economy, has done tremendous research to support the implementation of Baby Bonds, an innovative policy tool that creates publicly funded investment accounts for children. He is also striving to reframe industrial policy, which typically focuses on the interests of businesses, to center workers—recognizing that when all workers share in economic prosperity, the overall economy is stronger and more stable.

These leaders, among countless others, are creating models for collective action. Nick Tilsen, NDN Collective president and CEO and citizen of the Oglala Lakota nation, is demonstrating how to build collective power and scale place-based solutions that advance climate resilience and sustainable housing—problems bedeviling low-income, Indigenous, and tribal communities—throughout the nation.

Monica Simpson and the SisterSong Women of Color Reproductive Justice Collective have pioneered the reproductive justice movement, expanding reproductive rights beyond abortion to encompass the social and economic conditions that affect people’s reproductive health-care access and choices, including the ability to raise a child in safe and stable environments.

For Freedoms Executive Director Claudia Peña shows us that artists have a critical role to play in securing our democratic future as truth-tellers, healers, and creative forces that open hearts and imaginations to what’s possible.

Rev. Dr. Liz Theoharis, working alongside Rev. Dr. William J. Barber II as co-chair of the Poor People’s Campaign, demonstrates what solidarity looks like and reminds the nation that the struggle to create a thriving multiracial democracy is not about one group or another or one political party. It’s about right and wrong.

Finally, equity-focused leaders are pushing the government to live up to the nation’s founding ideals, aligning the apparatus of government with the goals of a multiracial democracy to ensure that the gains made now do not have to be fought for again. As PolicyLink president and CEO Michael McAfee has said, it takes more than grant dollars and diversity appointments to make government responsive and accountable to all, particularly those who have been oppressed and marginalized. It takes a governing agenda expressly committed to racial equity, with clear goals, measurable benchmarks, and transparent results. McAfee, in partnership with Glenn Harris, president of Race Forward, led the creation of the nation’s first comprehensive racial-equity blueprint for federal agencies, with resources and tools that are helping agency leaders implement President Biden’s executive order on racial equity. McAfee is also working with corporate leaders to embed equity principles, with accountability mechanisms, in their companies.

These leaders, among so many more, are rewriting the American story.

The United States has yet to witness a robust, just, vibrant democracy that equitably functions amid profound difference. But the aspiration is not new. In 1869, Frederick Douglass outlined his vision for the new multiracial democracy that seemed to be emerging after the Civil War. “Our existing composite population conspires to one grand end,” he said, “and that is to make us [the United States of America] the most perfect national illustration of the dignity of the human family that the world has ever seen.”

Once again, that opportunity is upon us.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Angela Glover Blackwell.