Malkia Klabu (“Queen Club”) is a loyalty program designed with and for young women (like this one from Shinyanga, who is on our Youth Advisory Board) to address multiple structural and psychological barriers to accessing sensitive health products. (Photo by Lauren Hunter)

Malkia Klabu (“Queen Club”) is a loyalty program designed with and for young women (like this one from Shinyanga, who is on our Youth Advisory Board) to address multiple structural and psychological barriers to accessing sensitive health products. (Photo by Lauren Hunter)

As the school term ends in Tanzania, 18-year old Neema is looking forward to spending time with her boyfriend back home, though she worries he has been unfaithful while apart. She feels anxious whenever her mother gossips about the “bad” girls who were expelled from school for getting pregnant and who shamed their families. The stakes are high. She’d like to reconnect with her boyfriend in hopes of being together long-term, but also avoid pregnancy and protect herself from HIV. To feel safe and confident about her boyfriend’s intentions, she wants him to get tested for HIV. Neema feels the stirrings of independence and wants to take charge by seeking health services on her own, but she must tread carefully to avoid suspicion amongst her family and community.

At first glance, Neema should be able to easily get what she needs. She regularly visits drug shops that sell condoms and oral contraception while running errands. Yet she can’t get her hands on these products, learn about them, or trust that they’ll allow her to better control her future. Why? She’s surrounded by adults in her life who closely monitor and police her behavior—adults who, despite their best intentions, enforce social norms that censure contraceptive use through fear and misinformation. Whether feeling ashamed to ask for something behind the counter, getting quizzed about why she needs sensitive products, or being denied outright because she’s wearing a school uniform, the shops aren’t designed with Neema’s explicit and subtler needs in mind. This represents a missed opportunity to sell a product that could prevent yet another teenage pregnancy, school dropout, and descent into cyclical poverty.

This isn’t unusual. Many public health innovations lack pathways to reach vulnerable customer bases, even with significant last-mile efforts. Polio vaccine teams, for example, often can’t reach the most physically and politically isolated communities harboring polio transmission. Business-as-usual is unlikely to solve such market failures. Even efforts to innovate for the “base of the pyramid” typically focus on lower-cost alternatives or improving distribution; they rarely address the larger contextual forces that keep products out of reach for customers like Neema. Previously, we’ve written about how patient-centered approaches can help overcome behavioral gaps in the last mile, but the challenge facing Neema exceeds what innovators can optimize with a patient focus alone. She has the desire, intention, and access (at face value) to get what she needs, but the distribution system, as designed, doesn’t allow her to act.

So how can social innovators account for these challenges when rolling out health products like HIV self-test kits or self-administered injectable contraception? We recommend building on our previous model of combining design thinking and behavioral science to not only design services for the core user, but also identify and creatively address broader barriers and cultural norms that would otherwise block uptake among vulnerable groups.

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR's full archive of content, when you subscribe.

Design Thinking for Localized, Low-Stakes Learning

Typical product diffusion starts with early adopters, slowly shifts to the broader population, and finally lands with more-vulnerable customers, as marketers learn more about them over time. For goods that drive significant social impact, we have a moral imperative to accelerate this process, and design thinking offers a practical way forward. Design thinking is a creative, empathetic innovation process that draws on ethnographic methods, and relies on rapid prototyping and real-world testing of potential solutions. The approach can help unpack ambiguous opportunity areas, revealing unmet needs among vulnerable customers that innovators might otherwise overlook.

A drug shop owner receives self-test kits from researcher Moza Albert Chitela, co-packaged with specialized referral information to youth-friendly health facilities. Feedback from shop owners and employees informed low-fidelity program prototypes before investment in the final solution. (Photo by Lauren Hunter)

A drug shop owner receives self-test kits from researcher Moza Albert Chitela, co-packaged with specialized referral information to youth-friendly health facilities. Feedback from shop owners and employees informed low-fidelity program prototypes before investment in the final solution. (Photo by Lauren Hunter)

In our own work to design “girl-friendly” drug shops, where young women can get sexual and reproductive health products and counsel, we interviewed and shadowed girls in their homes, communities, and during shopping trips to learn about their hopes, aspirations, and what’s holding them back—barriers they often won’t express with traditional research methods. At the same time, through story-based interviews and observations with drug shop owners and employees, we learned about their motivations and business practices, and how they serve different customers. By empathizing with both groups’ lived experiences—the foundation of design thinking—we quickly identified which aspects of community health services should be adapted to fit within each population’s unique needs, and solicited their feedback on low-fidelity prototypes before investing in the final solution.

We found that young women often visit drug shops, usually at the behest of their parents. Although contraception (and at some point soon, HIV self-test kits) are ubiquitous in these corner shops, young women with enough nerve to ask for a sensitive product are often hassled by shopkeepers who are willing to forego a sale, despite pressures to maintain profits, to reinforce social norms. From these insights, we conceived of a home delivery program for young women to discreetly get contraception and HIV self-tests at their doorstep. While this idea solved the “gatekeeping” problem, it failed to excite young women when prototyped and did nothing to help the most vulnerable girls—those without phones. Further, because we observed that shopping is often a quick, purpose-driven chore that leaves little room to explore new products, a delivery service would lack marketing touchpoints to grow demand. This low-stakes learning allowed us to quickly change course.

Feedback from girls and shopkeepers led us to home in on a loyalty program designed to address multiple structural and psychological barriers: sparking delight in otherwise mundane shopping by awarding prizes from mystery boxes stocked with desirable items, and printing coded symbols for sensitive products on the back of cards to which girls can point instead of having to ask aloud. Shopkeepers were excited about the program because it fit into their workflows, gave them implicit permission to provide sensitive products to young women through the buy-in of their professional association and coalition of participating shops, and could ultimately increase their bottom line.

Rather than accepting the status quo or campaigning for widespread cultural change, design thinking allowed us to create an immediate, actionable solution to circumvent harmful norms in ways that fold into girls’ and shopkeepers’ organic behavior. While we still support efforts to shift harmful mindsets, using design thinking can create more immediate market change and allow girls to access health products that improve their lives right away.

Researchers Agatha Mnyippembe and Kassim Hassan combine design thinking with behavioral science to design for the core user and creatively address barriers to the uptake of HIV self-testing and contraceptives among young women. (Photo by Lauren Hunter)

Researchers Agatha Mnyippembe and Kassim Hassan combine design thinking with behavioral science to design for the core user and creatively address barriers to the uptake of HIV self-testing and contraceptives among young women. (Photo by Lauren Hunter)

Behavioral Science for More Precision and Better Bets

While design thinking unlocks creative ideas and allows teams to progressively narrow in on a solution set, many aspects of product or service design are still based on well-informed guesswork. Design teams don’t typically pull in rigorously validated, external evidence (rather viewing themselves as charting new territory), and instead draw on real-world feedback from prototyping to help de-risk solutions. Yet it’s often impossible to prototype every aspect of a solution, and this creates risk. The stakes are especially high when the focus is on vulnerable customers like young women, who have less power or agency than a typical customer. Mitigating these risks is necessary if the ultimate go-to-market strategy is intended to account for the needs of all customers and those who influence their choices.

Combining insights from design thinking and behavioral science

Combining insights from design thinking and behavioral science

Incorporating the evidence-based tools and principles of behavioral science into insights and solutions generated through the design thinking process minimizes these risks by increasing the likelihood that the end-to-end experience will succeed, ultimately bolstering impact. Behavioral science is rooted in well-established theories of human behavior, characterized by behavioral biases and heuristics (like valuing the present more than the future). It’s best known for identifying the impact “nudges” have on improving the uptake, efficacy, or acceptability of an existing product or service. Many are familiar with the classic examples of how opt-out policies can increase organ donations or how automating enrollment into 401(k) plans can increase retirement savings.

On its own, however, behavioral science offers little structure to identify and clarify ambiguous barriers and opportunities, or to create solutions that address them. In our work with drug shops, behavioral science helped us shape and evaluate elements of different options, such as the default choices and incentives embedded within them. But it did not provide practical guidance on choosing between them, such as investing more in the home delivery concept or the loyalty card program. Rather, we used our design thinking insights to find our way to the most promising solution space. When coupled with design thinking, behavioral science becomes a tool to de-risk an innovative concept for maximum possible impact.

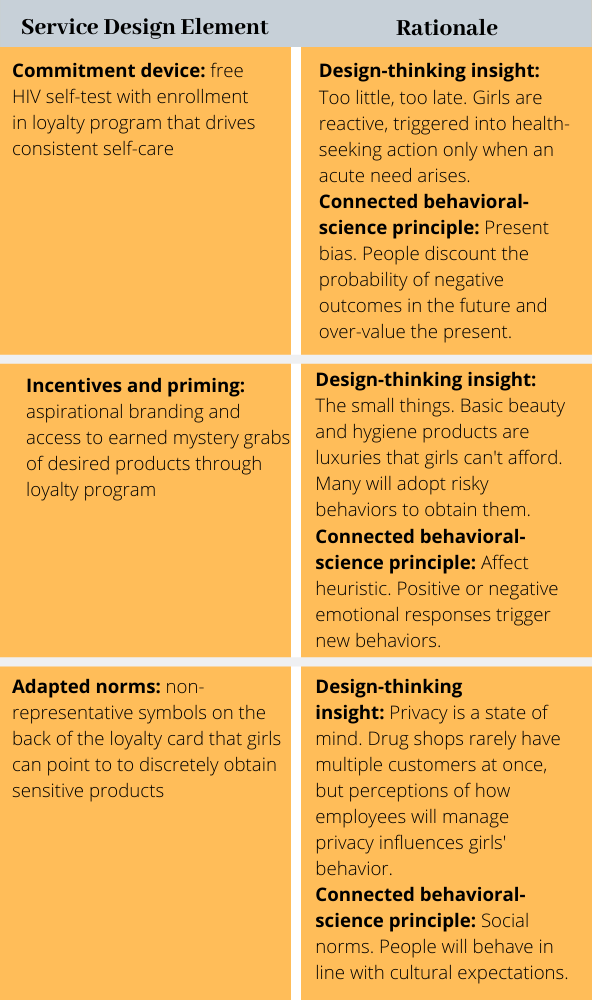

Mapping design-thinking insights to evidence-based behavioral principles can reveal strengths and weaknesses in service design. This worked well in our past work to drive HIV treatment adherence using patient-centered approaches, and we’ve continued to employ this approach to broader, market-blocking norms. In Tanzania, we mapped our insights against common biases from behavioral science and the corresponding nudges to address them (see chart). This revealed that the loyalty program worked within girls’ reality, but added emotional appeal and fun to their routine trips drug shops. It also leveraged multiple strategies from behavioral science, including commitments (planning to complete an action), incentives (rewards for being a repeat customer), and social ties (a feeling of belonging as a program member). By using nudges to mitigate risk on the smaller aspects of behavior change—for example, encouraging repeat visits to the shop with positive reinforcement, and reducing the gap between intentions and actions via commitment devices—we could focus on the bigger, structural bets of introducing the product experience to the drug shop channel, such as breaking down gatekeeper norms and building trust between shop owners and young women. During a soft launch of our loyalty program, we found that more young women bought and reported using contraceptive and HIV testing products. We have since implemented a randomized experiment in four wards in Tanzania to more precisely measure its impact.

When we use design thinking and behavioral science in tandem, our products and services can have much broader reach and faster adoption among groups who can benefit the most. In this way, girls like Neema can take control of their futures and thrive within communities, markets, and systems designed with them in mind.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Lauren Hunter, Aarthi Rao, Sandi McCoy & Jenny Liu.