(Illustration by Carolyn Ridsdale)

(Illustration by Carolyn Ridsdale)

Small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) create and sustain a substantial portion of jobs in emerging economies, contribute to innovation, and drive social impact. Entrepreneur support organizations such as incubators, accelerators, and fellowship programs play an important role for SMEs in emerging economies by closing entrepreneurs’ gaps in knowledge, capital, and networks; providing guidance to reach targets; and fostering entrepreneurship ecosystems. Research has shown the positive effects of entrepreneurial support on revenue growth, employment, and financing. However, upon completion of these programs, entrepreneurs are often back on their own, unless they participate in another support program. While entrepreneurs in industrialized economies have access to a broad range of professional services—industry trade associations, peer networking organizations, and consultants—that can help them navigate their growth over time, the fact that such services are less accessible in emerging economies results in a services gap.

In reviewing the field of entrepreneur support organizations across Africa and India, we identified more than 90 of the most visible accelerators, incubators, and fellowships. Typically, these organizations provide structured learning experiences, peer-to-peer interaction, mentoring, and access to investor networks over a discrete time period. Sixty organizations publicly shared details about their programs online. We found that 46 provide short-term, episodic services to entrepreneurs that last from a few days to six months, followed at times by a loosely organized alumni network. Recent data from the Global Accelerator Learning Initiative, a partnership between the Aspen Network of Development Entrepreneurs and Emory University, further undergird our findings on the gap in continued support for emerging-market entrepreneurs, showing that long-term services often don’t exist to support their growth but are direly needed.

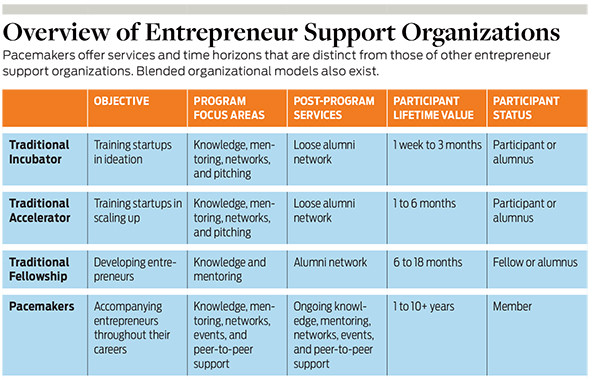

Our research has uncovered a novel type of entrepreneurial support organization that we call a pacemaker organization, or pacer, which offers an alternative for emerging-market entrepreneurs. Pacers serve entrepreneurs for the long run, from one year to a lifetime. Like pacers who help world-class marathon runners win races, pacemaker organizations help entrepreneurs achieve their goals in the marathon of scaling up an enterprise. Over the past two decades, some organizations have evolved their models to become pacers that help fill the gap in the entrepreneurial support landscape in emerging markets. Pacers adapt their programs and respond to entrepreneurs’ changing needs as they navigate how to scale up, maneuver crises, or pivot into new business domains.

The pacer model extends services over a longer time horizon than traditional support models, enabling SMEs to attain more social and economic progress. Pacers typically focus on post-revenue founders and their ventures, providing networking; continuous-learning opportunities; mentorship; long-term, trust-based peer engagement; and needs-based programming for founders and CEOs, which can range from preparing for a funding round to implementing a new performance management system to dealing with a cash flow crisis. Rather than drawing a distinct line between participants and alumni, pacers integrate entrepreneurs into their programming as members who can benefit in an open-ended fashion from pacers’ services. Some pacers work with their members over a long period even if they don’t take an investment stake in the firm, while others make small-risk capital investments, further strengthening their commitment and long-term interest in the growth trajectories of their members.

While entrepreneurial support organizations understand many of the challenges and opportunities of growing a business in an emerging economy, individual entrepreneurs don’t necessarily know when they will arise or how best to address them. Consider the case of Frank Omondi, CEO of Ten Senses, a macadamia- and cashew-nut processor and exporter based in Kenya. In 2017, Omondi participated in a one-year training program offered by the Stanford Institute for Innovation in Developing Economies, known as Stanford Seed. Yet, immediately after the program concluded, Omondi faced challenges in growing his enterprise. That’s when he tapped into Seed’s network of mentors and found Nancy Glaser, a seasoned Stanford Graduate School of Business alumna, who volunteered as a coach for several months by helping him address cash flow issues and get Ten Senses ready to find investors. Two years later, Omondi secured capital to further grow his business. In 2019, he needed expertise to develop a new, blockchain-based software to certify his fair-trade and organic nuts. He again tapped into Seed’s services, this time utilizing its internship program, working with a Stanford undergraduate to develop the new system.

LISTEN: Hear more from these authors on Spring Impact's Mission to Scale podcast.

In this article, we offer a blueprint of pacemaker organizations by drawing on the experiences of half a dozen such organizations. We interviewed representatives of pacers, including Endeavor, Unreasonable Group, African Management Institute, Harambe Entrepreneur Alliance, Entrepreneurs’ Organization, Y Combinator, Stanford Seed, and others. We explain the type of long-term—even lifetime—value pacers deliver to entrepreneurs, outlining their organizational structures, providing options for how other entrepreneur support organizations may wish to put the blueprint into practice, and showcasing some of the challenges that pacers currently face.

Our enthusiasm about pacemakers derives in part from our respective roles as organizational leaders of Stanford Seed and academic researchers. The pacer model has not yet been formalized and has evolved largely in a self-directed and organic way. But information now exists to begin formalizing the model and launching an industry-wide conversation, creating a stronger alignment across pacers and encouraging other entrepreneur support organizations to embrace pacer practices and address the service gap.

What Entrepreneurs Gain

Pacers tend first to offer intensive, short-term programs, like many other entrepreneur support organizations, and then graduate entrepreneurs into a long-term, post-program support infrastructure. Entrepreneurs, in turn, receive four principal benefits by working with pacers: access to continuous learning, extended business networks, meaningful peer connections, and needs-based services.

Continuous Learning | Pacers offer entrepreneurs long-term learning opportunities that help them anticipate and manage entrepreneurial challenges. Importantly, the need for learning doesn’t end after an entrepreneur completes a support program.

For example, Entrepreneurs’ Organization (EO) works with entrepreneurs who run businesses of more than $1 million in yearly revenue and holds executive education events both locally and globally through 211 chapters in 60 countries. Through partnerships with the Wharton School, Harvard Business School, and London Business School, EO runs the EO Entrepreneurial Masters Program, a three-year continuous-learning program for interested members. EO focuses programming prominently on its core value of “thirst for learning,” which encourages long-term professional and personal self-development. Shorter-term courses are also available anytime on topics ranging from strategy to finance. Marc Stöckli, global board of directors member and chairman elect of EO’s board of directors, says the program is not just about short-term business issues that arise. Rather, he says, “it’s [about] the full life cycle on the business side, but it’s also the full cycle for the whole [entrepreneurial] self.”

African Management Institute (AMI), headquartered in Nairobi, Kenya, delivers practical, blended learning to leaders of African micro- and small businesses, as well as training for middle managers of large companies throughout the continent. AMI operates programs using an advanced digital-learning platform with online courses and business tools for its members. Before 2020, the organization didn’t have a structured way of engaging with participants post-program. However, AMI cofounder and CEO Rebecca Harrison and her team realized that the same practices remained important for entrepreneurs upon completing a program. For this reason, in a new pilot, post-program entrepreneurs receive ongoing access to the digital platform to continue their learning as their needs evolve over time. In addition to these tools, members also have access to events every two months built around learning themes. Harrison believes AMI’s impact comes from implementation; hence, its post-programming is designed to support leaders in building new habits over time. In contrast with highly immersive and dedicated experiences in incubator and accelerator programs, AMI post-program participants access content as their entrepreneurial journey progresses, the AMI team observes.

Stanford Seed is active in 29 countries throughout Africa and South Asia and has trained more than 4,000 entrepreneurs and managers since it began offering programs in 2013. Participants engage in an intensive one-year, part-time management training to assess their company and build a long-term growth plan that aligns managers and employees as they incorporate changes. “Implementing a growth strategy is not a one-time deal. It’s a process that involves setting a course, measuring performance, and iterating” says Karen Bysiewicz, who designs the program’s curriculum. “Providing resources to help leaders implement their strategy is the next logical step in achieving growth.” Entrepreneurs can use their growth plan to decide which trainings and content to access. They can take part in webinars and events years after having completed the core programming and can access a resource library of leadership and business videos, as well as other content.

Extended Business Networks | Pacers give their members continuous access to broad networks of entrepreneurs, investors, universities, government representatives, and other stakeholders. These networks set the stage for growing a business and provide emotional support. Unreasonable Group has worked with almost 300 entrepreneurs and their growth ventures across 48 countries and has cultivated a global network of investors. The group’s senior director of global portfolio, Will Butler, and his team make introductions between entrepreneurs and investors on a regular basis. In addition, regional relationship managers are available to help facilitate connections with executive coaches, design talent, and other services. Stanford Seed cultivates connections with investors through a searchable network directory and by building partnerships with finance institutions to facilitate better capital options for members.

Pacers’ expansive geographical coverage is another important asset for members. EO believes that connection—particularly across geographies, experiences, and perspectives—fuels exponential growth. Small regional and global peer-to-peer experience-sharing groups help entrepreneurs connect locally and beyond borders. EO also enables members to structure groups by industry, as well as by shared interest—including a cigar-aficionado group.

The business networks that pacers forge continue to grow, thanks to the long-term nature of their relationship with members. For example, at EO, members begin as mentees and then evolve into mentors, thereby continuously growing their mentor pool. Members are also encouraged to take on leadership roles and receive training to equip them for roles in the chapter and beyond. Endeavor, which operates in more than 40 emerging and underserved markets globally, offers intensive support in securing capital, accessing markets, and forging connections with innovators who have faced similar challenges. Instead of paying a membership fee or giving out equity, Endeavor entrepreneurs commit to mentoring and investing in the next generation of what Endeavor calls high-impact entrepreneurs. “High-impact entrepreneurs are founders who dream big, scale up, and pay it forward,” says Endeavor South Africa managing director Alison Collier. She adds that 100 percent of Endeavor’s members give back by supporting other members and upcoming entrepreneurs.

Meaningful Peer Connections | Entrepreneurship can be a lonely profession. In response, pacers often focus on building supportive communities. A study by the Argidius Foundation of peer-to-peer networks Enablis Senegal and CEED Moldova found that they are effective in matching resources to the changing needs of individuals and their businesses.

According to Butler, Unreasonable Group offers members a deep level of connection through carefully crafted workshops and activities that build trust. During their 10-to-12-day initiatives, entrepreneurs participate in dinnertime conversations with members of Unreasonable’s investor community, including mentors and other entrepreneurs. “People’s armor comes off” after a couple of days, Butler observes. He believes the opportunity to break from day-to-day responsibilities for an extended time and engage in meaningful conversations with peers helps to create strong bonds. “Market conditions can shift,” he says, but “knowing you have a support system around you that understands the level of anxiety you shoulder … and who can help you navigate daily challenges is something special. A peer-to-peer support community can be a true competitive advantage.”

The Harambe Entrepreneur Alliance, founded in 2008 as a student club through Southern New Hampshire University, is another successful pacer, with 327 members, called Harambeans, and counting. Forging deep networks between old and new members is at the core of the organization’s work. The alliance hosts a conference to induct new members into the Harambean way of connecting and honoring relationships. “What we are doing is helping our members build trust, learn from each other, and invest in each other,” founder Okendo Lewis-Gayle explains.

Similarly, EO’s initiation of new members gives them an opportunity to build meaningful relationships through sessions focused on values. “After three hours into our values training, people really open up, even on Zoom,” Stöckli says. Because EO gives members access to global networks that are connected via groups on WhatsApp, WeChat, and other platforms, they can find each other in multiple ways. This ability to connect through the EO network facilitates what Stöckli calls “scaling trust”—the ability to forge deep, meaningful, and trusting relationships. EO strengthens these relationships by enrolling everyone in peer-to-peer experience-sharing groups of around eight people who meet once a month for three to four hours, following a structured agenda. In these meetings, entrepreneurs share unresolved business issues they have encountered, as a form of accountability toward meeting self-determined goals. Emotional issues involving self-development, business, and family are also integral parts of the discussions. Stöckli says that the ability to show honesty and vulnerability deepens these respectful, trusting peer connections.

In 2020, by leveraging the Seed network, 39 percent of members were able to conduct business with a peer, and 46 percent reported benefiting from peer guidance or mentorship. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Seed formed industry-based groups, enabling, for example, tourism-industry operators across countries to meet online and discuss ways to address declining business during shutdowns.

Demand-Driven Support | Entrepreneurs cannot anticipate all the ups and downs of growing a business venture, let alone predict changes in the global economy. For this reason, we find that pacers evolve over time by expanding their portfolio of content based on demand for additional services.

Having helped launch more than 3,000 companies around the world, Y Combinator (YC) is a well-known technology startup accelerator that provides seed funding. Over time, YC has extended its offerings for members preparing for Series A funding, post-Series A funding, and subsequent funding stages. YC also offers a service called office hours, in which members can receive targeted advice for current concerns and circumstances. EO has a program for early-stage startups with less than $1 million turnover that comes at a lower fee than a full EO membership.

After developing its training program, Stanford Seed created several forms of support for entrepreneurs who have finished their main training, including coaching, assistance from Stanford student interns, and pro bono consulting. For example, three years after completing the initial Seed Transformation Program, Jameelah Sharrieff-Ayedun, CEO of CreditRegistry Nigeria, turned to Seed consultant Claudia Salvischiani to build a strategic human resources system for talent management. As a result of this added support, Sharrieff-Ayedun says, “we have seen measurable improvements in our recruitment, our performance management, and our talent development processes.”

Unreasonable Group responded to its entrepreneurs’ needs for greater access to financing by developing a new group called Unreasonable Collective, an invite-only club for international investors that pools capital for them to co-invest in select impact-driven companies in their network.

Stanford Seed responded to the pandemic by designing new, Stanford faculty-led webinars aimed at supporting members in proactively navigating complex or unusual circumstances, covering topics such as cash flow management in uncertain times and human resources management during crisis. In the summer of 2020, 83 percent of Seed members reported participating in at least one pandemic-related program, either via a faculty-led webinar or a regional alumni event or directly, by accessing new resources on Seed’s social networking platform.

Pacers’ Effects

Pacers exist to offer open-ended support, believing that it will enhance ventures’ chances of survival in times of crisis, as well as their likelihood of scaling up. Offering services throughout enterprises’ full life cycle ensures continuity and improves their potential for success.

Pacers’ immediate effects are visible in members’ knowledge and behavioral changes after they go through a program, as well as in an expansion of meaningful networks. Extended support can lead to organizational transformation that drives growth. While more research on the topic is needed, pacers have contributed to long-term effects such as job creation, revenue growth, capital generation, and positive impact on lives through the sale of products and services. For example, Harambe members have generated more than 3,000 jobs and raised more than $1 billion in capital. Stanford Seed has contributed to its members’ creating more than 21,000 jobs, generating $183 million in additional revenues, and raising $421 million in capital. Furthermore, its members’ average job- and revenue-growth rates and rates of securing lending outpace local benchmark rates. Endeavor’s Catalyst fund is among the world’s top early-stage funders of startups that have become $1 billion-plus companies outside the United States and China. Unreasonable Group ventures have raised more than $7 billion in financing.

Pacers can also have unintended effects on their members and the larger entrepreneurial ecosystem. For example, in their selection processes, pacers can run the risk of favoring already successful entrepreneurs over those who are either marginalized or struggling. Such decisions can be affected by implicit biases. Stanford Seed, for example, runs a high-touch program focused on companies beyond the startup phase and runs into challenges in some regions when it tries to recruit female entrepreneurs who have sufficiently scaled their ventures to qualify for the program and benefit from its services. Female entrepreneurs in general may face barriers to growth, such as strict social constraints and other forms of gender bias, that selection panels do not understand well.

Building Long-Term Value

In reviewing pacers and interviewing representatives of their organizations, we identified four central building blocks that represent how they deliver long-term benefits to their members: robust volunteering networks, digital platforms, a distinctive funding mix, and a collectivist organizational culture.

Volunteers | Dedicated and skilled volunteers play a prominent role in a pacer’s organizational structure, helping to cost-efficiently deliver programs, enable scale, and engage with members in several capacities.

Typically, the volunteer pool consists of members and nonmembers. Members of pacemakers have a bond with their organization that cements their commitment to supporting the pacer’s mission, while nonmembers are often external experts, such as highly seasoned entrepreneurs and executives, who are looking for meaningful ways to contribute their skills.

Pacers often engage members to serve as mentors, coaches, and teachers. At YC, members who have graduated from the program are deployed as speakers, because entrepreneurs tend to identify more strongly with peers who have gone through the same experience.

Becoming an organizational leader is one of the most common roles for a member volunteer. EO has designed a comprehensive leadership structure, without which it would not exist. All leadership roles in the organization are occupied by volunteer members who are supported by professional staff, training, and a leadership conference.

Lewis-Gayle notes that Harambeans are an integral part of the organization’s growth. “Harambeans are involved in the nomination of candidates; they also interview the candidates, and then they vote,” he explains. In 2021, Harambeans selected 30 new members from 3,500 applications.

At Stanford Seed, all-volunteer network chapters are run by elected leaders and are essential in facilitating member interaction, curating regional and cross-regional networking, and organizing learning events. Davis Albohm, Seed director of global partnerships, says “chapters engage members who have a deep affinity for Seed, are solid organizers, and are well liked by their cohort members.” This approach results in localized programming driven by members, while staff guide strategy and operations.

Nonmembers also serve important capacities as pacers. At Endeavor, a global network of more than 5,000 external mentors—fellow founders, investors, and industry experts who donate their time—serve on advisory boards and offer one-on-one, on-demand mentorship on strategy and execution throughout the entrepreneurs’ journey. Typically, Endeavor entrepreneurs are in the network for 5 to 10-plus years, after which they sign up to mentor the next generation of members. Collier says that the advantage of receiving advice from a global network of volunteer mentors, versus investors, lies in the lack of conflict-of-interest issues and the depth and breadth of expertise available in the mentor pool.

Digital Platforms | Pacers use external-facing digital technologies like online searchable member directories, social media platforms, and online resource libraries to deliver content on growing a business, facilitate investor connections, and foster peer-to-peer support. AMI, for example, runs structured, blended programs employing online learning and networking platforms that it has now extended into post-program offerings. Unreasonable Group developed a proprietary platform called Unreasonable.app, which connects members, mentors, investors, and partners. The platform offers training guides and insights and facilitates authentic connections across the community.

YC developed a proprietary online alumni directory called Bookface where members can get advice. The platform’s technology enables users to identify specific members among its 7,000-alumni database with whom to connect and has resulted in higher sales and investments for entrepreneurs. Stanford Seed uses several platforms to connect members with investors and with one another, enabling efficient program and post-program services. Pivoting to virtual programs in the pandemic generated the additional, unexpected benefit of greater connectivity among members through Seed’s social networking platform.

In our research, we found that pacers are challenged by the need to power their models through digital platforms while preserving good client service. They sometimes opt for simple web-based solutions, such as member directories. Importantly, pacers do not see digital platforms as stand-alone solutions to create extended benefits and support. Instead, they use operational staff to curate member experiences and drive interaction.

At Unreasonable Group, 80 percent of entrepreneurs complete at least one check-in with a relationship manager each year to access investors, mentors, and other resources. If they are fundraising, they may even meet weekly. Similarly, Stanford Seed has three network managers across Africa and South Asia who help maintain personal relationships with members.

Hybridized Funding | To fund their services, pacers can collect philanthropic capital, donor grants, equity capital, and/or membership fees. We found great variation in the funding and observed that long-range programmatic efforts tend not to be financed solely by membership fees. We observed that some pacers’ funding is dominated by membership and program fees, while others subsidize costs through donor funding.

EO is funded fully by membership fees that vary according to the types of programming and legacy in the organization. Stanford Seed employs a philanthropic cost-share model in which philanthropic capital subsidizes member fees. Endeavor’s Catalyst fund is a rules-based co-investment fund established to invest in its entrepreneurs. The fund follows the price and terms set by the lead investor, whom the founder chooses. AMI’s 65-plus online courses and 2,000 practical tools are financed through working with multinational corporations, donors, and fees. And the Harambe Entrepreneur Alliance is financed through program fees, donations, membership fees from corporations and investors, and revenues from investments in Harambean-founded companies.

Funding a pacer primarily through membership fees establishes a strong link between providers and recipients. Revenues and program delivery costs are in sync, giving the pacer immediate member feedback on the pacer’s worth. A recent report by Argidius Foundation emphasizes the importance of charging some level of fees to optimize the participation of motivated entrepreneurs. By supplementing fees with philanthropic funding, however, pacers can better plan for the long term and build stable, high-value programs.

As we described earlier, most pacers invite in-kind contributions from volunteers who can offer teaching, mentorship, advising, and other services. This is a critical element of a pacer’s model, because if members had to pay for this quality of service, it could be prohibitive. Stanford Seed, for example, engages more than 250 volunteer consultants and coaches an active peer network to provide services at a fraction of the cost required to purchase them. The expansive networks are what help pacers provide services beyond a typical support program.

Collectivist Spirit | Pacers stand apart from other entrepreneur support organizations because of the collectivist spirit they establish among members. Pacers craft this culture through rituals, routines, norms, and symbolism intended to remind members of their shared values. Such culture-building establishes around pacers’ missions a sense of collective identity that goes beyond any one individual, emphasizing mutuality and interconnectedness.

Harambeans deliberately engineered their culture to center on a set of common values—“servant leadership, deliberate audacity, and enduring optimism”—as part of their alliance’s mission to transform Africa through members’ actions. The Harambean Declaration, a commitment that each member must sign as part of their initiation, is a ritual that symbolizes the members’ unity in their pursuit toward a goal greater than they are. “We publish and declare our intention to work together as one to unleash the potential of Africa’s people; pursue the social, political, and economic development of our continent; and fulfill the dream of our generation,” the declaration states. New members sign the contract in the Gold Room at Bretton Woods—the very place where the Bretton Woods Agreement and System, signed by delegates from 44 countries to establish a financial foreign-exchange system to promote financial growth, was ratified in 1944.

Stanford Seed cultivates collectivism by promoting values about building companies whose success can make a positive impact on society. The mission itself embodies a collectivist spirit: “to partner with emerging-market entrepreneurs to build thriving enterprises that transform lives.” Through job creation, improving customers’ lives, and other social-change efforts, these enterprises contribute to Stanford Seed’s ultimate vision of ending global poverty.

Pacers’ peer-to-peer support systems rely on collectivist values that emphasize mutuality, respect, vulnerability, and confidentiality. EO, Unreasonable Group, and Stanford Seed emphasize creating safe spaces for peer-to-peer support to flourish. At EO, guided by the core values of trust and respect, members learn the deep-listening practices of deferring judgement when others speak and offering feedback only when asked. Unreasonable Group and Stanford Seed curate bonding experiences that help members build meaningful connections. These occasions range from sharing strategic and operational challenges in groups organized by industry to communicating leadership challenges in peer groups where members engage in problem-solving. Such experiences, particularly early on, form the basis for members’ sustained involvement in pacemaker organizations.

Frontiers of Innovation

As pacers continue to evolve, they are exploring new frontiers of innovation. Specifically, we have identified five areas that pacers are actively cultivating to enhance their programmatic efforts.

Catalyzing Member Engagement | As pacers scale and their networks’ size increases, they risk losing the personal connections that create meaningful interactions. Since members self-select into a pacer, how they engage after a program is largely self-directed, so the model depends on their active commitment. Stanford Seed has observed that interaction on its digital platforms tends to decrease over time and that cultivating meaningful connections becomes harder as the network grows. Centrally coordinated conferences and regional network chapter convenings help with this challenge, as does the Reciprocity Circle on its social networking platform, where entrepreneurs can ask for and/or offer help. Similarly,

Unreasonable’s Butler notes that “it’s easy to engage those that are asking for help, but not everybody needs help all the time. Our fellowship is a lifetime fellowship, and levels of engagement will naturally ebb and flow.” At present, the pacer model is contingent on proactive members. As Stöckli explains, “EO is a gym and not a spa. You receive value only by engagement.”

Our interviews indicated that activating some members can be difficult and that creating network vibrancy requires continuous efforts. Four distinct member types seem to exist: passive members, who end engagement upon completing a program; occasional members, who dip in and out of programming as needed; active members, who engage on a regular basis and continuously access pacers’ services, as well as give back to the organization through volunteering; and network leaders, who continually engage, give back, and take on significant roles driving initiatives in the member network. Figuring out how to increase service utilization for the overall membership by activating and engaging dormant members who could benefit from services remains a challenge. Finding solutions to this challenge will become even more difficult as the membership bases of pacers grow. Pacers are innovating by making intentional efforts to stay abreast of the emerging needs of their members, measuring and showcasing their impact, and employing staff who are dedicated to community management.

Improving Diversity | Pacers have grown more aware of supporting a broad variety of entrepreneurs from different backgrounds, identities, geographies, and industries. At Stanford Seed, the pandemic drove the development of virtual programs that can be delivered to new regions at a lower cost, thereby improving geographic diversity. Thirty-two percent of new Seed members come from female-led enterprises; some regions are outpacing local rates of female business ownership, while others are falling behind. Similarly, EO is instituting organizational changes to increase female representation in peer-to-peer advisory groups. Ensuring that services are accessible to all demands that pacers reflect upon the current demographic composition of their members and companies to observe and address any biases in the membership process.

Capitalizing on Synergies | Pacers have a base of globally distributed members whose enterprises operate at different growth stages. Meeting diverse needs without increasing overhead costs demands creative solutions. Helping entrepreneurs overcome barriers to affordable and appropriate financing, particularly in emerging markets, continues to sit at the top of the agenda for pacers.

As in the case of EO’s collaborations with universities to provide executive education, several pacers have explored synergies in content delivery by working with academic institutions, while others have added investment vehicles by partnering with funders to address members’ resource needs. Stanford Seed has embarked on a new collaboration with the US International Development Finance Corporation that offers access to affordable loans and grants.

New opportunities to build synergies emerge as the membership size of pacers grows over time and they in turn become more attractive candidates for partnerships with outside institutions. Enhancing the quality of services must come not from pacers alone but also from like-minded collaborators.

Deriving Value from Measuring Impact | Pacers are seeking new ways to evaluate their impact and share insights. Most pacers publish data on the overall performance of their members’ ventures. But, given the long-term and multifaceted nature of pacemaker support, attributing the impact of various post-programmatic efforts to member outcomes, such as employment creation, external capital raised, and revenue growth, is an impact evaluation challenge. We observed that some pacers are beginning to embrace experimental and quasi-experimental methods to measure the impact of their programs.

Stanford Seed has tried to improve its data collection over the past decade. Instead of collecting voluntary surveys annually from members, it now makes them mandatory if members want to access post-program services. The organization’s annual survey response rate has increased from 58 percent in 2018 to 80 percent in 2021. Stanford Seed shares the data in annual impact reports, including detailed benchmark data for entrepreneurs. In this way, members can now benefit not only from post-program activities but also from insights developed by its growing database.

AMI also requires members to complete post-program surveys for two years if they seek to benefit from additional post-program services. Generating impact data that are beneficial to pacers and their stakeholders is an active frontier of innovation and also contributes to building a spirit of collectivism.

Delivering Hybrid Programs | The pandemic created massive disruptions in pacers’ program delivery models, causing them to switch from face-to-face interactions to digital services. This step has challenged the very sense of community, peer engagement, and trust that is fundamental to what pacers offer members. Since the pandemic is not over, it is still too early to determine whether participants who joined during the pandemic and attended virtual programming will become and remain active contributors to the community.

Pacers are now figuring out how to adapt their model to hybrid forms of interaction. For example, because YC found remote work productive for founders and investors during the pandemic, the organization considered having face-to-face interactions at the beginning and end of a program while conducting other activities remotely. Finding the right balance between tech-enabled programming and face-to-face interactions is a top priority of pacers.

How to Adopt Pacer Practices

Any entrepreneur support organization, even if it provides short-term programming, can consider embracing pacer practices for some or all participants. The decision to expand the types and time horizon of support should be informed by market demand, the organization’s impact to date, and whether its impact could be extended through a pacer model. Many of the needs that members will have can be anticipated, while only some—such as enduring a business shutdown during a global pandemic—are unexpected. Shifting toward a pacer model requires thinking about maximizing members’ lifetime benefits. Embracing pacer practices thus means transitioning away from a conventional alumni network and toward an integrated, multifaceted member network.

First, let’s consider some practices that are relatively straightforward to implement and don’t require major investment. One of the most valuable resources of any entrepreneur support organization is its alumni. Alumni members’ knowledge and wisdom are existing but often underutilized assets. One quick, high-impact win is to re-engage and activate particularly successful alumni by inviting them to give talks to current members. Organizations can take short surveys to identify knowledge demands in the alumni population, as well as identify alumni speakers who can help fill those gaps. Such endeavors can start informally and become more formal over time. In a similar vein, entrepreneur support organizations can engage well-respected alumni in strategy sessions, charting out a new vision of how the organization can benefit their alumni. They can then be called upon to cultivate an alumni network. Engaging alumni in such ways can contribute to the collectivist spirit at the heart of pacers.

Pacers must consider the spectrum of needs that businesses have, the spectrum of services they can offer, and the appropriate time horizon for delivering such services.

Second, think about what can be changed and experimented upon within a support organization. For example, start by reviewing the organizational culture to begin to build a collectivist spirit. Updating the organization’s mission, values, and revising (re)initiation rituals at member events can also contribute to the creation of a stronger culture. Designing better immersive experiences can create longer-lasting bonds between members and the organization. Such efforts should be driven by leadership and supported by the rest of the organization.

Third, consider making more long-term investments, such as building a digital platform that connects members and gives them lifelong access to content, volunteers, and the network. An increasing number of choices for such platforms are available, and costs are falling. In addition, try establishing regular events to reconnect alumni with the organization and build meaningful connections between member cohorts. Such activities can cost an organization money in the short run, so scouting new types of capital to finance the operation should accompany a more comprehensive organizational change.

The risk of shifting toward a pacer model is not insignificant. By embracing only a few elements of pacers, an organization may risk creating an unsustainable model. For example, creating a digital platform without a collectivist spirit as a solid foundation could prompt alumni to use the platform once and never return, because of a lack of meaningful connection. Transitioning to a vibrant infrastructure that supports entrepreneurs over the long term requires a conscious commitment that must align with an organization’s mission and capacity.

Reflections

Long-term support infrastructures such as those provided by the growing cadre of pacers are important ingredients to cultivate sustainable entrepreneurship ecosystems in emerging markets. We applaud existing and new efforts in making pacers more widespread.

As pacers grow in number, some questions emerge for them to consider regarding the ideal utilization of their services. For example, how much support is too much support? Should a pacer continue to support a struggling business that may be beyond the point of salvaging? Or, on the flip side, is there a point at which a successful member should pay for market-rate consulting, instead of turning to its pacer? When, if at all, should entrepreneurs “graduate” from post-program support?

Pacers must consider the spectrum of needs that successful and struggling businesses have, the spectrum of services they can offer, and the appropriate time horizon for delivering such services. Right-sizing services can ensure that entrepreneurs are not prematurely abandoned to make do on their own, and that entrepreneurial support organizations in emerging markets can maximize their impact in the long run.

Want to hear more from the authors of this article? Listen to their interview on Spring Impact's Mission to Scale podcast, part of a special series with the authors of SSIR's Summer 2022 issue.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Sonali V. Rammohan, Tim Weiss, Darius Teter & Jesper B. Sørensen.