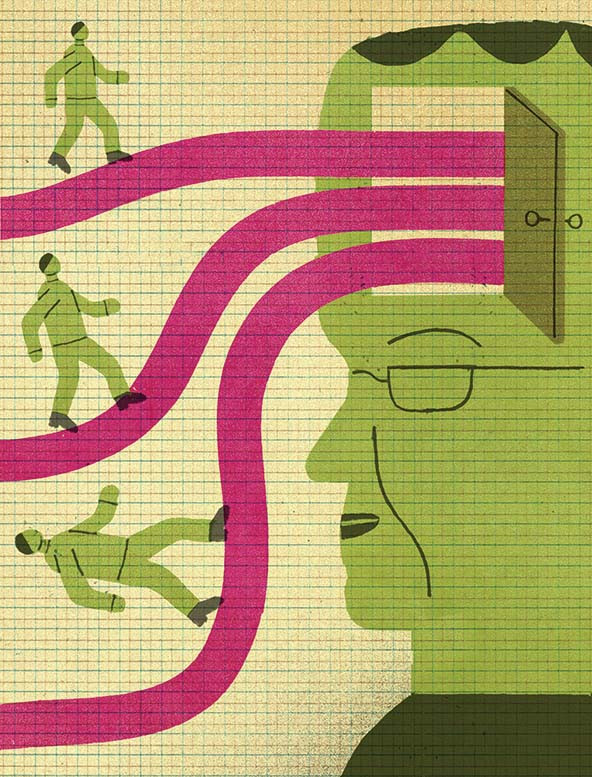

(Illustration by David Plunkert)

(Illustration by David Plunkert)

During the first weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic, Los Angeles County officials faced an urgent crisis. They knew that hundreds of thousands of the county’s 10 million residents might go hungry because of job losses and the breakdown in the community food supply, but they didn’t know who was affected and didn’t have a ready means to find out.

Money wasn’t the problem. The county had federal emergency funding to provide food assistance. But it lacked information to reach the right people, some of whom had never been food insecure before. The way food insecurity is measured in the United States does not capture granular, real-time changes on the ground. The data that county leaders had to rely on in April 2020 had last been updated in 2018. Complicating matters, public-health orders to stay at home meant that the food-assistance landscape had to be drastically reimagined. The county needed help, but its Emergency Food Security Branch did not have a research arm to analyze the rapidly changing circumstances.

Too often, when faced with crises such as this one, policy makers must rely on a combination of obsolete data, guesswork, and luck to help the public. In this case, however, a new approach was possible. Public Exchange was conceived and built at the University of Southern California’s Dornsife College, where I serve as dean, to deploy academic expertise at scale to address societal problems and to reinvigorate public trust in research as serving the public good.

A Lack of Infrastructure

In spring 2020, Public Exchange quickly assembled a team of USC food systems and public-health experts, behavioral scientists, and spatial scientists to help the county tackle the problem. Surveys by the team quickly revealed that nearly 40 percent of low-income households in LA County experienced food insecurity in April and May 2020. But leaders also needed data on food outlets and private food-assistance programs. So Public Exchange brokered innovative partnerships with organizations including Yelp and findhelp.org. Integrating these partners took a concerted effort, but their novel datasets proved to be vital, offering a more complete perspective on the complex and unpredictable changes happening to the food system. Ultimately, the team’s insights helped drive campaigns to expand and scale socially distanced food distributions, increase enrollment in government food programs, and redirect targeted assistance to those with the most acute need. As a result, LA County delivered 10 million pounds of food to the households that were most affected.

Stories like this one—where urgency meets ingenuity to address a crucial need—defined society’s response to the pandemic. But a research university is not likely to be the first place you think of to spearhead urgent social-impact collaborations involving leaders across the public, private, and nonprofit sectors.

To be sure, researchers at universities routinely produce work that improves lives and communities. Faculty publish academic papers, journal articles, white papers, and books that provide transformative insights and new ways of thinking. But in many cases, the specific problems that a policy maker, community leader, or CEO seeks to solve are not on a researcher’s agenda. This gap needs to be filled.

Academic researchers are not just experts in a narrow field—they are highly trained and creative problem-solvers capable of both leading through inquiry-driven research and applying academic knowledge and methods toward more immediate and direct impact. But they too often lack the opportunity to contribute in ways that have immediate societal benefit—not because of lack of interest or inability, but rather because of the absence of critical infrastructure to make research expertise more accessible beyond the academy.

Public Exchange invites social-impact leaders outside the university to bring in challenging problems that they are trying to solve.

This lack of infrastructure is costly both for academia and for society. Polling indicates that the public’s opinion of scientific expertise and trust in academic research has declined over the past three years. At a time when we urgently need innovation, this finding is very disturbing. Remember that discoveries from our research universities have underpinned almost every gadget you’ve ever touched and most modern medical breakthroughs. Yet, the prevailing public debate about the value of universities focuses almost solely on our role as educators with little acknowledgment of our vital research mission.

This dynamic may explain why, in the five years that I served as Columbia University’s inaugural dean of science, overseeing nine world-class science departments, I never once fielded a call from a civic or business leader looking for an expert’s help. And as we built the foundation for Public Exchange at USC, we heard repeatedly that though potential partners did not doubt that university researchers possessed valuable expertise, they frequently expressed skepticism about whether they could activate and access it in responsive ways.

Readers of this Stanford University-based publication, in particular, may be familiar with the “tech transfer” model that led to the creation of Stanford’s Office of Technology Licensing (OTL) in the early 1970s. The OTL enabled Stanford to accelerate the process for licensing intellectual property built on breakthroughs in computer science, engineering, and biomedicine for use in commercial applications. Today nearly every leading research university has adopted this model, and it has spawned some of the world’s most influential companies and innovations.

The United States will continue to rely on tech-transfer partnerships to accelerate commercialization of materials that enable the transition to clean energy, machine-learning innovations, and novel disease treatments. But this model taps only a small fraction of the expertise that lives inside our research universities—institutions that are home to the world’s most celebrated economists, political scientists, psychologists, spatial scientists, ethicists, and countless other scholars. They, too, could be engaged in a more proactive and efficient way to help leaders overcome issues—especially those that cannot be solved by technology alone.

To understand the missing infrastructure, it is important to note that the well-established pathways for publication and technology transfer all begin with questions generated by researchers. This investigative autonomy is by design and continues to result in foundational discoveries that are critical to human progress. But no clear and efficient pathway has been available for a civic or business leader with a specific goal in mind to seek relevant expertise from academic researchers.

This is where Public Exchange comes in. While researchers continue to run their own research programs, Public Exchange invites social-impact leaders outside the university to bring in challenging problems that they are trying to solve. It then assembles teams—often interdisciplinary—from the thousands of researchers at USC and affiliated universities to deliver the specific expertise and insights needed. It streamlines matchmaking, contract negotiation, and project management—processes that frequently complicate or derail partnerships between academic researchers and outside organizations.

Building a Network

Public Exchange employs full-time professional staff who come from government, industry, and nonprofit backgrounds, with experience solving the types of problems that their research teams address. The team manages projects from start to finish, ensuring that civic or business partners receive the insights they need on time and in the right format. Faculty experts are compensated for their research, and administrative bottlenecks are reduced, so researchers have an incentive to contribute without compromising their own scholarly agenda. Many Public Exchange projects have also resulted in new publications for our participating faculty.

As Public Exchange has evolved and refined its model, we have seen how this approach is driving progress in our communities. For example, Public Exchange’s USC Urban Trees Initiative—a collaboration with the City of Los Angeles—has so far guided the strategic planting of 700 trees in areas of the city with limited shade and poor air quality. It also brings attention to university research in new ways. This project was featured on Los Angeles NBC4 News, as well as in The Guardian, Outside magazine, and several other outlets. This coverage is important. In today’s highly polarized political landscape, if the public cannot see and feel the positive impact that research universities can have on our lives, the resources and support required to sustain these national treasures will continue to decline.

Public Exchange has been made possible with modest philanthropic seed support, and our team expects it to be self-sustaining through project funding in the coming years. We are also beginning to explore the potential of this model to expand into a Public Exchange network involving research universities across the country. Other such networks exist that take different approaches with distinct but related goals (e.g., the Anchor Institutions Task Force, a research and movement-building organization that seeks to improve the economic, social, and civic health of communities through local anchor institutions such as universities and hospitals), and they too have the potential for scalable impact.

As a community, research universities need to do a better job of foregrounding the value of our research mission. Pushing out our research findings and products will always be important, but we can do more. We must also better position ourselves as more accessible partners to address immediate and pressing issues. Not only will more robust engagement help restore public trust in academic expertise, but also it will ensure that society can rely on its most creative problem solvers to help address the most pressing issues of our time.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Amber D. Miller.