Creating Strategic Value: Applying Value Investing Principles to Corporate Management

Joseph Calandro Jr.

240 pages, Columbia Business School Publishing, 2020

The principles of value investing have resonated with savvy practitioners in the world of finance for a long time. Creating Strategic Value explores how the core ideas and methods of value investing can be profitably applied to corporate strategy and management. The book builds from an analysis of traditional value investing concepts to their strategic applications. It surveys value investing’s past, present, and future, drawing on influential texts, from Graham and Dodd’s time-tested works to more recent studies, to reveal potent managerial lessons. It explains the theoretical aspects of value investing-consistent approaches to corporate strategy and management and details how they can be successfully employed through practical case studies that demonstrate value realization in action. Creating Strategic Value analyzes the applicability of key ideas such as the margin-of-safety principle to corporate strategy in a wide range of areas beyond stocks and bonds. It highlights the importance of an “information advantage”—knowing something that a firm’s competitors either do not know or choose to ignore—and explains how corporate managers can apply this key value investing differentiator. Offering numerous insights into the use of time-tested value investing principles in new fields, Creating Strategic Value was written for corporate strategy and management practitioners at all levels as well as for students and researchers.—Joseph Calandro Jr.

+++

Introduction*

"Investment is most intelligent when it is most businesslike. I should add that it is most successful when it is most businesslike."—Benjamin Graham1

Business students need only three well taught courses: How to Value a Business, How to Think About Market Prices, and How to Manage a Business.—Inspired by Warren E. Buffett2

A great deal has been written about value investing but, until fairly recently, there was no formal attempt to categorize the development of this influential school of thought over time, as far as I am aware.3 This is important because it is difficult to forecast where a school of thought is going without first understanding where it has been. Therefore, to kick things off, I will profile my thoughts on value investing’s past and present, and then offer suggestions on what its future may hold.

Founding Era: 1934 to 1973

The “official” founding of value investing can be dated to the year 1934 with the publication of Benjamin Graham and David Dodd’s seminal book, Security Analysis. The strategic concept upon which value investing was founded is as insightful as it is simple; namely, that assets purchased for less than their liquidation value (estimated as current assets less total liabilities or “net-net value”) are a relatively low-risk form of investment due to the “margin of safety” afforded by the discount from liquidation value. Risk in this context is defined as the possibility and amount of loss.

As the discipline evolved over time, some investors started estimating margins of safety off earnings power and even growth value in addition to liquidation and net asset values. In fact, value investing scholars classify three different methods of “value investing” given the different methodologies that can be used: “classic” value investing as practiced by professionals such as, for example, the late Max Heine and Seth Klarman; “mixed” value investing as practiced by professionals such as Mario Gabelli and the late Marty Whitman, and “contemporary” value investing as practiced by professionals such as Warren Buffett and Glen Greenberg.4 Regardless of approach, however, the cornerstone of professional value investing has always been, and will always remain, grounded in the margin of safety.

The Founding Era effectively ends with the publication of the 1973 edition of Benjamin Graham’s immensely popular book, The Intelligent Investor 4th Revised Ed., which distills lessons from Security Analysis to a non-professional audience. Shortly after the book’s publication, in 1976, Mr. Graham passed away at the age of 82.

Post-Graham Era: 1973 to 1991

The start of the Post-Graham Era coincided with the great 1973-74 bear market that, amongst other things, presented numerous investment opportunities akin to those seen at the beginning of the Founding Era. Therefore, it is no coincidence that such a market environment saw the ascendancy of a number of highly successful value investors such as Gary Brinson, Jeremy Grantham, John Neff,5 and others. Nevertheless, it was during this period that modern financial economic theories began to take hold. In the book, Capital Ideas, Peter Bernstein profiled these theories, all of which find disfavor with professional value investors:

- Economists believe that market prices are “efficient,” while value investors know that, at times, market prices can behave extremely inefficiently resulting in margin of safety-rich opportunities for the patient, liquid and informed investor;

- Economists believe that capital structure is “irrelevant,” while value investors know that capital structure is always relevant;

- Economists believe that investments should be guided by modern portfolio theory (MPT) while value investors understand, and carefully exploit, the fact that the volatility and correlation statistics of MPT are not representative of a portfolio’s risk and return profile (where risk is once again defined as the possibility and amount of loss); and

- Economists’ option pricing models do not consider underlying value; conversely, to a professional value investor, value is a component of option pricing just like it is a pricing component of every other economic good.

Despite the success of professional value investors during this era, the challenge for Graham and Dodd’s successors was to determine how the basic insights of value investing could be reinterpreted for modern investors, and to demonstrate the significance of that reinterpretation given the market conditions investors were wrestling with.

Modern Era: 1991 to Present

To address this challenge, value investor Seth Klarman, co-founder and president of The Baupost Group, picked up where Benjamin Graham left off, literally. The 20th and final chapter of Mr. Graham’s The Intelligent Investor is titled, "'Margin of Safety' as the Central Concept of Investment," while the title of Mr. Klarman’s 1991 book is, Margin of Safety: Risk-Averse Value Investing Strategies for the Thoughtful Investor. The lucidity of Mr. Klarman’s book, coupled with his investing track record, helped to set the tone for the Modern Era of value investing.

Support for this position can be found in the influence that Margin of Safety has had on all of the prominent value investing books that were published after it, from Bruce Greenwald’s aforementioned book (chapter 13 of which profiles Mr. Klarman), to the sixth edition of Security Analysis (for which Mr. Klarman served as lead editor) to Howard Marks’s well-regarded value investing book, The Most Important Thing Illuminated (which was endorsed by, and contains annotations from, Mr. Klarman).

A strength of modern value investing theory is that it can be applied to all forms of investment, not just stocks and bonds. For example, consider derivatives. Bestselling books like The Big Short profiled a number of investors who really did “catch” the 2007-2008 financial crisis by purchasing credit default swaps (CDS) at margin of safety-rich prices prior to the crisis. One of these investors was Mr. Klarman.6

How did these investors “do it”? While the specifics of their investments are not publicly available, there is a real-time record of similar investments in the influential and long-running newsletter, Grant’s Interest Rate Observer, which is published by value investor/historian/financial analyst/journalist James Grant. A compendium of Mr. Grant’s newsletters leading up to “the big short” were published in the book, Mr. Market Miscalculates where Mr. Market is Benjamin Graham’s euphemism for the short-term-oriented trading environment that dominates the financial markets. On page 171 of that book, which was taken from the September 8, 2006 edition of Grant’s Interest Rate Observer, it was noted that a hedge fund was “expressing a bearish view on housing in the CDS market by buying protection on the weaker tranches of at-risk mortgage structures. At the cost of $14.25 million a year, the fund has exposure to $750 million face amount of mortgage debt.”

To see how margin of safety-rich this investment was at the time, consider that one way commercial insurance underwriters evaluate risk pricing is to divide the premium of risk transfer (in this case, $14.25 million) by the amount of risk (in this case, $750 million), which in this example gives a “rate on line” of $0.014. By comparison, it is common for some businesses to pay $40,000 or more per year for $1 million of general liability insurance, which equates to a “rate on line” of $0.04.

Post-Modern Era

With value investing successfully being applied to so many asset classes—stocks, bonds, real estate, derivatives, etc.—what could a “Post-Modern Era” entail? One answer to this question could find increasing applications of core value investing principles to corporate strategy and management.

Professional value investors have generally been skeptical of corporate managers. For example, in Security Analysis, Benjamin Graham and David Dodd observed that, "It is nearly always true that the management is in the best position to judge which policies are most efficient. However, it does not follow that it will always either recognize or adopt the course most beneficial to the shareholders. It may err grievously through incompetence."7 There have been many other examples since this was written.8

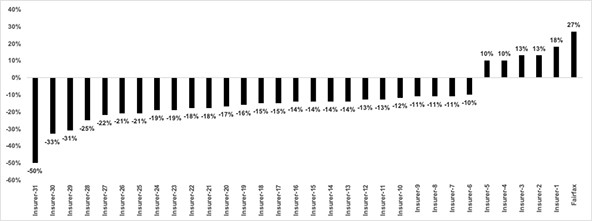

However, there have also been powerful exceptions. Consider, for example, the case of Prem Watsa who is the founder, chair and CEO of Fairfax Financial Holdings. Prior to the 2007-2008 financial crisis, Mr. Watsa purchased economically priced CDS, which reportedly generated a gain of more than $2 billion against an investment of $341 million. While the specifics of Mr. Watsa’s position are not publicly available, one can surmise that because he is a corporate manager the CDS he purchased were appropriate for the balance sheet he was managing, which is to say hedging. In general, there are three ways to manage the risk of a significant balance sheet exposure: (1) reduce it, (2) diversify away from it or (3) hedge it. Each of these alternatives can be informed by value investing in general, and by the margin of safety principle in particular. In the case of hedging, the results of Mr. Watsa’s position speaks for itself: Exhibit 2 profiles 10% or greater changes in property and casualty insurance company performance in the third quarter of 2007. The financial performance of Fairfax Financial Holdings—shown at the extreme right of the exhibit—is materially greater than the rest of the insurance industry at the time.

Margin of Safety-Based Hedging

One objective of this book is to provide a theoretical foundation for a value investing-based approach to corporate strategy and management. More on this in a minute, but first we will return to the development of value investing as a school of thought.

Classifying the different eras of any school of thought is subjective, and as such frequently requires anchoring to key dates. For example, the Baroque Era of music "officially" ended with the death of J.S. Bach. Maestro Bach, of course, never knew that his death would end an era any more than Benjamin Graham could have known that some future author would date the close of the Founding Era of value investing with the 1973 edition of his book, The Intelligent Investor. Nevertheless, such classifications are useful for both practitioners and researchers, especially when contemplating what the future may hold.

Data source: Dowling & Partners, IBNR Weekly #39, October 5 (2007), p. 8. The names of the remaining 31 insurers are available from Dowling; order of the names was changed by me.

Whether value investing comes to influence and help define corporate strategy and management in the future or not, investors and corporate managers alike can only benefit from studying the lessons of Mr. Graham and his followers. Professional value investing has been applied across a variety of asset classes and market environments and, when applied skillfully, it has generated exceptional returns at relatively low levels of risk. To facilitate this from a corporate management perspective, this book is structured in two parts.

Part 1 establishes a theoretical foundation for value investing and corporate management, which is important because, first and foremost, value investing texts pertain to investing, not to corporate management. Building off of this foundation, Part 2 brings the theory to life via historical case studies of value realization in action. The chapters in this part of the book are somewhat technical, and should be approached as such.

Similar to my first book, most of the chapters of this book (including this Introduction as well as chapters 2 through 11, inclusive) are based on research papers that were published academically, and then rewritten for this book. I publish papers on the practical side of the academic literature, and have found it a useful outlet to both develop and disseminate my ideas. By collecting and rewriting a number of these papers for this book, I hope to reach a larger audience, and to advance the continued study of value investing, particularly as it applies to corporate strategy and management for both practicing executives and researchers alike.