(Illustration by Juan Bernabeu)

(Illustration by Juan Bernabeu)

We are a team of three University of Minnesota professors whose professional and academic experiences span the business, government, and nonprofit sectors, in fields including law, public affairs, and corporate strategy. For the past eight years, we have worked closely with early- and mid-career professionals from business, government, philanthropic, and community organizations who are interested in collaborating for positive social change. We have studied and coached their efforts to launch and sustain cross-sector initiatives, and we have built and taught graduate- and executive-education curricula on the possibilities and pitfalls of such efforts.

We have observed how difficult it can be for collaboratives to turn their shared motivation to do good into an actionable plan for positive social impact. To respond to this challenge, we have developed an agenda-setting process for cross-sector initiatives. Our process recognizes that—like startup businesses—cross-sector initiatives work with limited resources and untested hypotheses. Lean Startup methodology offers a path to product launch that accounts for these restrictions by emphasizing relatively quick and inexpensive product introductions to test and adjust the business model on the basis of customer feedback.1 The experiments that permit a startup business to collect feedback on the product with limited resources are known as minimum viable products.

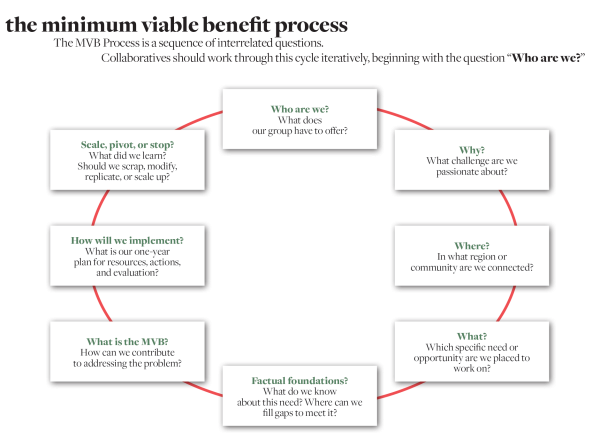

Our agenda-setting process for cross-sector initiatives takes a similar structured-experimentation approach.2 It is organized around designing a minimum viable benefit (MVB)—an actionable contribution to the larger challenge that a group can introduce and assess. The information generated from the MVB aids the collaborative in determining whether to continue and scale their efforts, pivot, or stop. The MVB Process thus allows cross-sector initiatives to concentrate on agenda-setting despite uncertainty and limited resources. The value of the MVB Process is twofold: It advances promising cross-sector initiatives, and it builds collaborative leadership skills and connections for group members, potentially increasing community capacity for future cross-sector action.

The MVB Process allowed a group of rising professionals in St. Cloud, Minnesota, to work through how they might be able to fill job vacancies in their region. The group included professionals from marketing and communications, community development, human rights, education, banking, and construction. They convened in late 2019 and early 2020, prior to the COVID-19 lockdowns. They had observed that their region was experiencing a high level of vacancies in middle-skills jobs—positions that require more than a high school education but less than a four-year college degree. They hoped to match these jobs with workers from communities looking for economic advancement opportunities, enabling economic growth and enhancing their region’s reputation for inclusivity in the process.

We asked the collaborative to focus first on who they were—their skills, knowledge, life experiences, and connections—so that they would have a clear picture of the resources available for their work. We then connected them to a group of graduate students who could help them evaluate relevant labor-force participation, demographic, and employment data to check industries with open jobs and local populations that might be available to address them. The analysis led them to focus on the relatively large number of construction industry jobs and two local populations—Somali immigrants and returning veterans—whose skills could be a good match for these vacancies. Further analysis showed that, of these two populations, the Somali community had a higher incidence of unemployment and underemployment and was historically reliant on verbal communication, rather than online posting, for information about available jobs. This information suggested that the collaborative could organize their agenda around developing in-person outreach strategies for construction industry recruitment within the local Somali community—an initiative that, if successful, could then serve as a model for other employment recruitment efforts.

Before the group could refine their strategy, the COVID-19 pandemic hit, thwarting the initiative’s strategy of in-person communication as the world went into lockdown. Despite this derailment, group members felt positive about what they had learned from the process of trying to match job candidates with available employment opportunities in their region.

“Through this process, we identified new partners and approaches to hiring that we wouldn’t otherwise have thought of,” one member notes. “I also learned important new ways of thinking about standard practices and how small, collaborative steps can help our community get to a better place. I’ve brought that appreciation into my current work across organizations to improve our region’s childcare infrastructure.”

Participating in the MVB Process thus helped the collaborative to avoid getting stuck in the agenda-setting phase of their efforts and to build confidence in their ability to contribute to the economic and social life of their region.

Why Collaboratives Get Stuck

We have identified four recurring obstacles that hinder collaboratives in setting an agenda for civic engagement. The first is the daunting complexity of the societal challenge the group wants to address. Consider, for example, the far-reaching impact of opioid addiction on rural communities in the United States, affecting not only addicts and their friends and families but also their employers, for- and nonprofit health-care providers, courts, and prisons. The crisis has numerous social and economic causes and produces many interconnected problems. Organizations and individuals can become mired in the complexity of such issues and subsequently fail to locate a starting point from which to conceive an agenda for their effort. We refer to this obstacle as “getting stuck in the overwhelm.”

A second obstacle occurs when collaboratives craft highly ambitious action plans that address the multiple factors and systems affecting an issue but exceed their capacity to execute. Limitations on what the group can accomplish can include time, knowledge, data-gathering capacity, and available collaborators, as well as funding and authority. We saw such constraints impede a group that focused on advancing equitable participation in the 2020 US Census. They brainstormed ideas for assisting historically underrepresented communities with census participation, such as staffing buses that could travel to specific neighborhoods for the data collection. They met several times to zero in on what they could specifically do to facilitate equitable census participation. Yet their efforts fizzled when they realized that they had neither a clear understanding of the issues nor the time to research the significant obstacles to census participation or existing efforts to address them.

A third recurring obstacle is achieving alignment on both defining the problem and setting priorities on problem-solving. Alignment can be particularly daunting for cross-sector initiatives, given their need to find common ground despite diverse organizational affiliations, goals, and expectations. This challenge confounded a group of government agencies, neighborhood organizations, environmental organizations, landscaping companies, and forestry businesses that came together in 2011 to address the arrival in Minnesota of the emerald ash borer, an insect native to northeastern Asia that has killed hundreds of millions of ash trees since its discovery in North America in 2002. Group members struggled over priorities. Should they devote resources to pesticide injections to protect individual high-value trees in known infestation areas? Or should they focus on protecting unaffected forests by controlling the movement of wood products that could introduce the insect into new regions? Should they remove ash trees to avoid possible injuries to people and property from infested, falling trees? Their proposed time frames (short- versus long-term), geographic scales (local versus regional), and approaches (fight versus accept) also differed significantly. Given their different problem definitions—individual trees or whole forests, prevention or adaptation, optimizing ecological health or minimizing property damage—they were unable to agree on joint activities other than monitoring and reporting on the spread of the insect. While these actions contributed valuable data to understanding the shape and scale of the issue, they did not proactively help to control the insect’s spread.

The fourth obstacle originates in the lack of defined processes or roles—in other words, the absence of an established decision-making structure—in startup collaboratives, as compared with established partnerships or formal organizations. Some of the groups with which we have worked include participants who have prior governance expertise or previously established relationships with each other, which can compensate to some degree for these deficits and ease decision-making. Others have the resources to hire or dedicate staff to establish and administer a governance structure. Without at least one of these attributes, the startup collaboratives we have observed tend to struggle to figure out what to focus on, what to try to accomplish, and how to move forward.

The Agenda-Setting Process

The MVB Process helped a group of five young Minnesotan professionals develop an actionable agenda to overcome these four obstacles. They met in a fall 2020 interdisciplinary, graduate-level course in cross-sector leadership at the University of Minnesota and had a common desire to mitigate the negative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Minnesota residents’ health and economic well-being. The group consisted of a government meat inspector, law students specializing in privacy law and immigration, a program manager for a corporate philanthropic foundation, and an immigrant-rights community organizer.

Although they believed in the power of collaboration to increase their impact beyond what they could accomplish individually, the group members initially struggled to identify how they could meaningfully address this daunting challenge. They found a specific problem that they could focus on by discussing their skills, experiences, expertise, and connections. Through identifying the resources they had, in addition to noting those they lacked, they determined that they were uniquely positioned to work on one aspect of the pandemic: breakdowns in the meat supply for American households, resulting from the rapid spread of COVID-19 in the cramped working conditions of meatpacking plants.

As home to several of the country’s largest pork-packing plants, and with a high concentration of meatpacking jobs, Minnesota is crucial to the national supply chain for meat. Meatpacking-plant workers and their family members suffered from illness, as well as layoffs, while some plants were temporarily closed during lockdowns. After analyzing the issue and the landscape of related programs, the group found that meatpacking employees came to work even when sick because they did not understand their right to paid time off and could not afford to lose their income. The group also found that workers were reluctant to report COVID-19 infections or exposures, for fear of having to reveal information about undocumented family members to public-health workers. Meatpacking companies needed the workers, yet neither they nor state government agencies were transparent about the levels of infection and measures to protect workers. The group then identified a need that they could quickly act on by using both this information and their collective knowledge of the meatpacking industry, immigration and privacy law, community organizing, and language fluency: the barriers that Spanish-speaking, immigrant meatpacking workers faced in reporting COVID-19 infections and accessing health-care resources.

The group decided to create a free, app-based tool kit for labor- and immigrant-oriented nonprofits, social-service agencies, and one major meatpacking company to inform Spanish-speaking immigrant workers in southwest Minnesota about their workplace protection rights, including how to report illnesses confidentially. Their intervention would allow multiple sectors to cooperate in informing workers of their rights and providing confidential mechanisms to report illness, receive support, and slow the spread of COVID-19. It was a low-stakes effort, but if it worked it could be scaled for use at other meatpacking plants, language groups, or industries where non-English speaking immigrants experienced similar risks or barriers to reporting COVID-19 infections and accessing care. The group was able to move past being overwhelmed by the scope and scale of COVID-19’s devastating effects by iteratively exploring their specific capacities and researching community needs until they found a match, and then being willing to start with a modest intervention to test their approach.

(Click to enlarge)

(Click to enlarge)

The MVB Process helped the meatpacking group advance their goal by asking them to address a sequence of interrelated questions. The process consists of questions that we ask groups to consider individually, in order, and iteratively:

Who are we? | We ask collaboratives to think critically about who they are and what their capacity is. This exploration requires time and a genuine desire to benefit from the opportunity of working with individuals with diverse perspectives. What are the group’s individual and collective professional, cultural, geographic, and sectoral frameworks? What subjects and places are they knowledgeable about? What are their preferred forms of data and analysis, task competencies, and values? Focusing on self-exploration at the outset helps individuals within groups deepen their knowledge of one another, which can build trust and level the informational playing field, especially if some group members have preexisting relationships and others do not.

In addition, this self-examination can provide a foundation for highlighting and exploring potential alignments—of skills and concerns—that can help the group coalesce around their MVB. It can also uncover potential resources that group members can draw on but might not have focused on initially. For example, we encourage lawyers to think of their knowledge in terms of not only their legal expertise but also their training in conflict engagement and their life experiences. Finally, and perhaps most important, starting with self-exploration acts as a counterweight to the temptation to set an overly ambitious agenda by asking the group to acknowledge both their limitations and their strengths.

Crafting a useful intervention also requires a collaborative to have knowledge of both the facts relating to the specific issue they have identified and any extant efforts to remediate that issue in their target location.

Why? | We ask groups to identify the social challenge that they are collectively motivated to address. We intend this to be a relatively quick and straightforward part of agenda-setting that helps group members define the boundaries of their shared motivation and reinforce their personal investment in the collaborative effort. We recommend this action of specifying the high-level challenge as the second, rather than the first, step in the MVB Process so that it occurs within the context of the collaborative’s prior exploration of who group members are and of where they have and lack credibility, connections, and knowledge. Focusing on larger social concerns without this context in mind can increase the risk that proposed interventions will be unworkable or ineffective.

For example, in 2019 we worked with a group of young business and law professionals who were passionate about preserving the natural environment. They were particularly concerned about protecting wilderness areas from proposals to expand mining activities in an area of northern Minnesota known as the Iron Range, a series of iron-ore mining districts around Lake Superior. They hoped to create opportunities for economic diversification that would also help to preserve the environment. Unfortunately, throughout their agenda-setting process, they focused almost exclusively on the larger goal, failing to take into account their own limitations in conceiving of how they—as long-term Twin Cities residents who had visited this area as tourists but who lacked firsthand knowledge or expertise of living and working there—might achieve it. They brainstormed about how to convene local individuals and groups to help new and existing businesses craft environmentally sensitive business plans, but they couldn’t come up with specific, credible plans without a greater knowledge of local values, goals, and constraints. Consequently, their work failed to advance.

Where? | We ask collaboratives to focus on a specific place that they are knowledgeable about. This knowledge can come from a variety of sources: group members might have lived there, or their work or professional training might have given them insights into how the challenge that they identified in the “Why?” step is experienced on the ground. Like the previous questions, this question is intended to focus the group on a viable MVB based on what they might do in a particular place and at a particular time. In the meatpacking example, the group decided to concentrate initially on one specific meatpacking plant not only because it was a significant local employer but also because group members’ connections and skills could facilitate the tool kit launch there. More specifically, a group member was a community organizer in the county where the plant was located and thus was already connected to labor and safety-net organizations that could help inform employees about the tool kit. In addition, the plant had many Latinx immigrant employees who communicated in Spanish, and the collaborative’s members included fluent Spanish speakers who could help translate the tool kit.

(Illustration by Juan Bernabeu)

(Illustration by Juan Bernabeu)

What? | We ask groups to narrow the broad social challenge they named in the second step by identifying one or more of its specific aspects that are relevant to the place they have chosen and the impact they seek. If, for example, they identified the larger challenge of digital inclusion in step two, specific issues to consider in this step might include training, access to hardware, and improving internet quality. This step helps the collaborative to orient their higher-level motivation—their “Why?”—toward a specific action that they will later shape into their MVB, along with the information they have assembled in the “Who?” and “Where?” steps.

Factual foundations? | As the US Census group discovered, crafting a useful intervention also requires a collaborative to have knowledge of both the facts relating to the specific issue they have identified—whom it affects, how and when it affects them, and what’s known about its causes—and any extant efforts to remediate that issue in their target location. Ideally, they would also examine successful interventions in other locations to consider whether elements of those approaches might be relevant in their place. Groups that lack these factual foundations or that make unfounded assumptions should aim to obtain and incorporate this information before proceeding with their work. Failure to lay these foundations can lead groups to craft solutions that fail to engage with their chosen problem, are duplicative of existing efforts, or overlook the opportunity to adapt a model that has been successful elsewhere.

We encountered this difficulty in 2022, when we worked with another collaborative from St. Cloud that was also focused on the abundance of job vacancies in their region; the difference was that this group was specifically interested in entry-level jobs. They began their MVB Process with the assumption that a significant cause of this problem was that students at local universities and colleges left the region upon graduation. Working from this starting point, the group first set out to create a series of networking and mentoring events for students graduating from these higher-education institutions to help them establish ties to the region. However, once the collaborative examined the available information relating to postgraduation student location, they found that these individuals stayed in the area at a rate much higher than they had assumed it would be. With this evidence, they concluded that retention should not be their issue and refocused their efforts on attracting people to the region.

What is the MVB? | Up to this point, the MVB Process prepares groups to be creative and pragmatic about what they can do. We now ask the group to articulate a hypothesis about a nonduplicative intervention within their capacity that could address their chosen issue in their selected place and, if successful, could potentially be replicated or scaled. They are then ready to define their MVB: a version of the intervention that is developed just enough to test one or more of the leading assumptions in their hypothesis. For example, a group focused on the positive impact of reading aloud to children on their success in school might decide to work on a tool to help parents with fewer resources easily find books. Based on their understanding that Android phones are in widespread usage among the parents in their community, the group then might decide to develop an Android phone app. The MVB, then, might be a bare-bones version of the app, with, say, a limited number of books on it, which would allow the group to test uptake on a parenting tool delivered via this platform. If they received positive feedback, they could then launch a second version of the tool, one that would allow them to test the age groups and kinds of books that generate most interest and activity and are therefore most likely to stimulate reading aloud. Future versions of the tool could then take this information into account.

The MVB Process offers a step-by-step guide to agenda-setting that lies within the capability of groups even without a funded backbone organization, governance experience, or significant preexisting relationships.

How to implement the MVB? | We recommend that collaboratives design and execute a one-year plan to launch their first MVB. The plan should cover all actions needed to develop, produce, launch, and gather feedback on it. These actions include, for example, engagement with other stakeholders and partners, designation of the responsibilities of each group member, assembly and assignment of resources, a timeline, and an evaluation strategy for assessing success and capturing lessons learned.

Scale, pivot, or stop? | The next step requires groups to evaluate the MVB to determine how to proceed. Relying on feedback and outcomes, the collaborative must choose one of three pathways: further develop or extend the reach of their intervention; adjust it to address feedback; or abandon the effort if their hypothesis is not supported and they are not able to modify the intervention to address its shortcomings. Even if the group decides to quit, we request that they document their learnings from testing their hypothesis, since this information can be a resource for subsequent efforts by the same group or to others interested in related issues.

Collaborative Persistence Builds Civic Capacity

The MVB approach addresses obstacles we have repeatedly observed to effective cross-sector action. It emphasizes identification of an intervention that a collaborative can produce, test, and learn from in a relatively short period of time. This focus can make cross-sector work seem more manageable and can guard against getting stuck in the overwhelm. It can also guide fledgling initiatives away from approaches that they lack the time, knowledge, experience, or resources to achieve. Its “Who?” and “Why?” steps can provide a common groundwork and vocabulary for prioritization and problem definition, and the time groups take to explore their capacity and shared motivation can build trust that facilitates necessary alignment.

Conceiving and launching an MVB is to act from a stance of optimism—of saying, “Based on what we know, we believe this might work. Nobody has tried this exact approach in this place before, so let’s try it and see what we can learn.”

In addition, the MVB Process offers a step-by-step guide to agenda-setting that lies within the capability of groups even without a funded backbone organization, governance experience, or significant preexisting relationships.3 While tool kits, diagnostic exercises, and taxonomies for launching and implementing cross-sector initiatives have emerged in recent years, they can require additional time, staff support, or other process-management resources that many of the rising leaders and startup collaboratives that we work with do not possess.4 In our experience, such groups often benefit from a road map that offers relatively simple, sequential directions. By providing these groups with a way forward, the MVB Process seeks to counteract the discouragement and disengagement that can result when an initiative stalls. Communities lose out when they leave this talent on the table.

Despite its advantages, the MVB Process isn’t suitable for every collaborative. Groups that are bound by a funding agreement with specific deliverables, work with clearly applicable models, command significant resources or political or economic power, have previously tackled social innovation projects together, face regulatory requirements, or start with a trusted agenda-setting process and structure won’t need or be able to follow the MVB Process precisely. Moreover, the process can create some challenges for groups that use it. When they introduce a tailored and limited MVB to address a complex challenge, collaboratives can find themselves under attack from others concerned about the same issue for thinking too small and addressing only one aspect of it. They may be pushed off course if they lack confidence in themselves or their agenda.

The MVB Process, however, can help to manage a defining tension of cross-sector collaboration between, on the one hand, the complex causes and presentations of a multifaceted social issue and, on the other, the finite capacity of any particular collaborative.5 The steps of the MVB Process account both for this broader context and for group limitations. Defining an MVB involves hypothesizing about how actions that a particular collaborative can implement and evaluate quickly might contribute to the larger goal of addressing a significant social challenge. The MVB Process explicitly includes the requirement that groups consider whether their initial efforts can or should be adapted, replicated, scaled, or discarded. Each of these outcomes generates lessons that can be used to build knowledge of what is effective and what is not in different contexts. As an iterative process, the MVB approach seeks to help collaboratives find incrementally more significant ways to contribute to broad-based action without getting stuck in their inability to parse an overwhelming issue into actionable parts, as the emerald ash borer group was.

Although the need for systems change can be a powerful motivation, it sometimes impedes cross-sector action. Orienting activities around systems change can often backfire by overwhelming collaborators or pushing them to set unattainable agendas that they cannot implement. In addition, an emphasis on systems change can lead groups to ignore potentially effective initiatives that would involve making better use of an existing system—by modifying, adding to, or scaling it.6 The MVB Process helps collaboratives home in on tractable problems for which they can develop, test, adapt, and expand solutions.

The MVB approach is a strategy for persisting through the challenging work of collaborating for positive social change. Conceiving and launching an MVB is to act from a stance of optimism—of saying, “Based on what we know, we think this might work. Nobody has tried this exact approach in this place before, so let’s try it and see what we can learn.” We encourage groups to think of their initial MVB as the first link in a chain to which they or others who are also committed to the larger effort can add additional links—an MVB 2.0 or 3.0, for example. Independent of its success or failure, each MVB can generate resources—better information, a more compelling problem definition, partial successes—that can make successive efforts stronger. Social innovation requires such collaborative persistence.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Vanessa Laird, Kathy Quick & J. Myles Shaver.