SPONSORED SUPPLEMENT TO SSIR

SPONSORED SUPPLEMENT TO SSIR

Innovating for More Affordable Health Care

This special supplement includes eight articles that explore new ways for social investors to spur innovations that create better, faster, and less expensive health care in the United States. The supplement was sponsored by the California HealthCare Foundation.

The great irony of the transformative health care reform legislation passed in 2010 is that although the law promises access to care for 30 million Americans, it relies on an outdated structure woefully ill prepared to serve them. Constrained resources, flawed economics, rising costs—how can a health care system under so much strain survive such an expansion? The answer will be found in creativity.

Over time, the most dynamic health care institutions have boosted their creative metabolisms, so to speak, with promising methods for vetting new ideas and technologies. More recently under Chief Technology Officer Todd Park, the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has become known as a budding innovator, too—and none too soon, given the magnitude of the challenge it confronts.

Like all institutions in this era of reform, HHS is leveraging the entrepreneurial experience of people like Park to reinvent how it does business. But as Park explains, HHS is aiming for more: “We are trying to do things in government that will facilitate entrepreneurship and innovation in the private sector. Think of it as meta-entrepreneurship.”

The department can be thought of as the largest, most important health care institution in the country. As the agency that administers Medicare and Medicaid, it in effect picks up more than 47 percent of the nation’s health care tab. Private insurance companies also look to the HHS for benchmarks that help them establish their own pricing. And the department’s newly created Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation is now responsible for creating new payment models, such as systems to pay physicians’ salaries instead of fees for service. HHS plays an equally significant role as a health care regulator, too.

What happens at HHS will therefore help shape the course of the entire industry. As they endeavor to create a culture of innovation inside and outside the government’s bureaucracies, Park and his colleagues are learning important lessons for the field.

AN ELEPHANT LEARNS TO DANCE

When Silicon Valley entrepreneur Todd Park joined HHS as chief technology officer (CTO) in August 2009, the department was the least likely of government institutions to be described as nimble or creative. It certainly did not look innovative. As the health reform debate reached a crescendo, HHS was more often described as a bloated elephant.

Part of this perception owed to its size. HHS is a colossus, housing 10 of the nation’s major domestic policy administrations, including three of its largest: the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, the National Institutes of Health, and the Administration for Children and Families. HHS has 73,000 full-time staff, which is roughly equivalent to the payroll of Cisco Systems. It also has an authorized annual budget of $902 billion. Its spending authority is 50 percent larger than the 2011 general funds of all 50 states combined.

Big bureaucracy was foreign territory to Park. He had captured the Obama administration’s attention as the co-founder of Athena Health, an early health information technology startup specializing in revenue cycle management for medical practices. When Athena Health debuted on the NASDAQ stock exchange in 2007, the then 34-year-old Park became a multimillionaire and an instant symbol of Silicon Valley success.

Back in fall 2009, it was far from certain that Congress would pass a health reform bill. But Park’s move to HHS hinted that the department was about to undergo some radical change of its own. To start with, until Park agreed to become its CTO, the job had never existed at HHS. It turned out that Park’s superiors, HHS Secretary Kathleen Sebelius and Deputy Secretary William Corr, had an unusual take on the new role.

“When I got here my boss told me, ‘Todd, you’re a change agent, and your job is to originate initiatives that will help HHS harness the power of data and technology in innovative ways to improve health,’” Park recounted in an interview. This was not the traditional CTO mandate. “The title is a bit of a red herring—I’m really an entrepreneur-in-residence,” Park explains, slipping into his Silicon Valley dialect.

An entrepreneur-in-residence, or EIR , works under the tutelage of a venture capital firm and is typically expected to source new deals, form a new company, or help manage an existing company in the firm’s portfolio. Inside a bureaucracy as complex as HHS, succeeding as its lonely EIR was prone to be even more difficult than managing its IT systems might have been. But Park had little time to dwell on this fact.

A lesser-known mandate of the health reform bill of 2010 was a requirement that HHS build a consumer service that could help consumers “take control of their health care.” The goal was to make information more accessible to average Americans.

It was a vague but daunting objective. To put a finer point on it, the law required that a new Web portal provide details about prices and coverage for every public or private insurance plan on the market. The portal should also explain confusing topics like tax credits and reinsurance programs to small businesses, and it should educate consumers about how the labyrinthine insurance industry works. Later it would add preventative care advice, too. To a technology entrepreneur, the product might have been described as a Yahoo! for health insurance.

Only days after Congress passed the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act to reform the health care system, the task of building such an all-encompassing portal landed on Park’s desk. Sebelius gave her new CTO just three months to build it. Even by Silicon Valley’s adrenaline junkie standards, three months to get from concept to launch was extremely tight.

“No one thought we could do it,” Park says. “It was like, ‘There shall be this site and it shall allow any American who walks up to it to get all the information on every insurance company in America—and good luck!’” In perfect bureaucratic form, Park’s HHS colleagues didn’t actually expect him to deliver it. “They expected us to launch with a placeholder [site],” he says.

By the time they set to work, Park’s team had just 75 days to launch the portal. On July 1, 2010, HHS debuted HealthCare.gov, and it was anything but a placeholder site. Consumers found an intelligent engine that, on the basis of responses to a few questions, could deliver a customized overview of insurance plans. They could toggle through Web pages to compare thousands of plans for their benefits, participating providers, and eligibility requirements. The portal was also interactive, regularly asking users how HHS might improve the site.

The response was a groundswell. Since it launched, 5.7 million people have visited HealthCare.gov. If simple when compared with inventing a faster microchip, the portal is nevertheless an innovation that has helped transform HHS from a remote bureaucracy into an accessible presence in the lives of millions of newly engaged health care consumers.

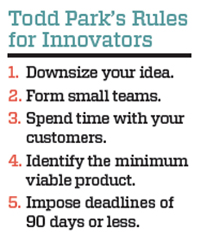

FIVE RULES FOR INNOVATORS

Building successful innovation projects like this inside such an unlikely institution, and in so short a time, wasn’t an accident. Park has developed a tried-and-true set of rules that guide his work.

“I wouldn’t say we have a system yet, but there are things we are doing that are meant to be systemic,” Park says. He breaks down his method into the five standard operating procedures that follow. (See “Todd Park’s Rules for Innovators” below.)

RULE #1: Downsize Your Idea. Step one is to decide on the right projects to pursue. Park uses an easy-to-remember, two-part filter: First, the project must have the potential to generate a significant impact that furthers the organization’s mission. Second, the project must be small enough for just five people to tackle.

“Start with the institutional mission or the high-level goal,” says Park, “and then ask yourself: What are the [individual] things most likely to produce a big ‘delta’ against that goal?” The smaller things with the largest mission impact are the projects you should take on.

At HHS, the high-level goal was to help consumers take control of their health care using technology and data—again, a mission both vague and grand. The information portal, however, was a comparatively small idea that had the potential to deliver a lot of bang for the buck in advancing the high-level goal. It was also much simpler to execute than, say, a full-scale software application, which would have required a more complicated information technology architecture, much more code, and many more people.

RULE #2: Form Small Teams. Once you’ve downsized your grand mission into a realistic project, form a core team of no more than five people. Call it “The Rule of Five.” Go larger than five, Park cautions, and the incremental costs of full-time employees outweigh the benefits of the teamwork. “You just cannot get more than five people to think like a single brain,” Park says. Core teams of 10 or 20 are simply too big to think collectively or to track what’s going on.

Now, Park doesn’t think that groups of five can accomplish everything. Some projects need worker bees to get things done. For example, Park added 15 researchers to pull together the data about insurance plans for the portal. Park thought of them as contractors, but he confined ownership over the project to a core unit of five, including himself.

Projects also need the right mix of people. People outside the Beltway know that the best way to organize an innovative effort is to have the strategy people, the technology people, and the operations people all blended together on one team. “Employees one through five should be really hard to tell apart,” Park says. “They are all like [Navy] SEALs—people who can be called upon to do any of the necessary tasks. They are always in the same room, and they are all focused on the same question: ‘What does the customer want?’”

RULE #3: Spend Time with Your Customers. When first asked to explain his methods at HHS, Park responded tartly: “I can tell you what we didn’t do. We didn’t do a focus group!” Instead Park and his team spent their time conducting “deep dive” conversations with real people.

Big organizations often hire consultants and market researchers to compile enormous research reports. Park believes that innovators are better served when they skip expensive, formalized research and instead spend lots of time asking customers questions like “Would you use this product?” and “Do you like it better this way, or that way?”

People cannot want what they do not yet know. “A focus group would never have come up with the Internet or e-mail,” Park says. “All the focus groups in the world will not help you discover the customer’s inarticulable preference.” He says focus groups are great for assessing incremental improvements to existing products, but they are useless for identifying opportunities to create breakthrough innovations that people don’t yet know they desperately need.

RULE #4: Identify the Minimum Viable Product. Innovators commonly make the mistake of trying to do too much, too soon. They try to build a space shuttle instead of a glider. Finding your “minimum viable product” means building the smallest possible offering that will still deliver value to the customer.

“The probability that your first idea is the right idea is incredibly low,” says Park. Athena Health’s first business plan was to manage medical practices. But this wasn’t the product that doctors needed. Doctors really wanted a smarter, easier way to collect payments from insurance companies, so Athena Health transformed itself into a provider of revenue cycle management services.

Knowing that the first product is likely to be insufficient, Park recommends instead going to market with a stripped-down offering that your customers can begin to use right away. Then collect feedback—and iterate, iterate, iterate to improve the product from there.

This approach also reinforces Rule #2. When you engage customers early in the process, you increase the odds of delivering what they need, which increases the odds of success.

RULE #5: Impose Deadlines of 90 Days or Less. If inertia is the enemy of the incumbent, urgency is the innovator’s friend. The best way to sustain a sense of urgency, Park says, is to impose deadlines on your project of 90 days or less.

Imposing short deadlines gets you to market sooner, which gives you an earlier chance to uncover and fix your product’s shortcomings. Aggressive deadlines also have the added benefit of enforcing discipline. When a team has just 90 days to show results, it is less likely to let anything distract it from that goal. The team can achieve incremental progress as well, which keeps everyone motivated.

If you think your project requires more time to launch, you haven’t thought small enough. Go back to Rule #1.

THINK SMALL, DEMAND SPEED

You may have noticed a pattern here. All of Park’s five operating procedures are mutually reinforcing. In the end, they come down to achieving bite-size yet outsize results quickly. They have nothing to do with the physical environment your team works in, or with the technology tools they use. “Just putting [your staff] in a building with translucent walls and giving them iPads isn’t going to make them innovative,” says Park. But by following his guidelines, the process of innovation itself can be scaled.

Since building the health care portal, Park has gone on to lead even larger projects successfully. For instance, the Community Health Data Initiative (CHDI) is a public-private program to help local leaders and public health workers more clearly understand, and improve, the performance of their community health systems. Web tools mine HHS data on the regional use of resources, rates of avoidable hospitalizations and readmissions, the prevalence of diseases within communities, and the determinants of disease, such as access to healthy food.

The project originated as a plan to build, in-house, the largest-ever health data map. Park and his team quickly realized their original goal was too big to be a glider, to borrow his catchphrase. HHS released the data to the public and let outside coders do the heavy lifting instead.

Next, Park expanded the CHDI project into a national Health Data Initiative (HDI). Another joint effort between HHS and the private sector, HDI aims to spur entrepreneurs to develop consumer software and smartphone applications that tap into government health care data. Once secreted away in hidden databases, these data troves are also now available to anyone at HHS affiliate websites like Health.Data. gov and HealthIndicators.gov, and through sites operated by private sector partners like Health 2.0.

In the last year, Park has sponsored HDI “code-a-thons” in San Francisco, Boston, and Bethesda, Md., working together with Health 2.0. Hundreds of developers have produced dozens of new tools, including 45 applications that Park claims “present real, viable business models.”

As it both innovates internally and fosters public-private projects like these, HHS is setting its sights on a transformation of health care. Its work, in turn, demonstrates valuable lessons for entrepreneurs in all environments.

“It is absolutely possible to innovate in a way that is replicable,” Park concludes. “The modus operandi is to come up with an idea, find three to five people to make it real, form a virtual startup around them, and run the thing like a Silicon Valley operation. This is the polar opposite of how large companies function. It is anathema to how government functions. But if HHS can do it, anyone can do it.”

See the complete healthcare supplement.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Carleen Hawn.