SUPPLEMENT TO SSIR SPONSORED BY GRANTMAKERS FOR EFFECTIVE ORGANIZATIONS

Smarter Philanthropy for Greater Impact

This special supplement includes eleven perspectives on “scaling what works”—what it means, what it takes to do it right, and what needs to happen to increase the impact of successful solutions to social challenges.

-

What Would It Take?

-

Emerging Pathways to Transformative Scale

-

Pathways to Scale for a Place-Based Funder

-

The Road to Scale Runs Through Public Systems

-

From Innovation to Results

-

Perspectives on the Social Innovation Fund

-

Partners in Impact

-

We Need More Scale, Not More Innovation

-

More Resources, More Co-Investors, More Impact

-

In Collaboration, Actions Speak Louder than Words

-

Leveraging a Movement Moment

What would it take to provide all children with the services and the support they need to stay in school and graduate? What would it take to break the cycle of poverty once and for all? What would it take to bring new skills and real opportunities to the millions of people living and working on the fringes of today’s economy?

These are the kinds of questions that motivate those of us in the social sector to get out of bed and go to work and do our jobs. Every day, nonprofit organizations and social entrepreneurs across the country are doing heroic work to alleviate problems from poverty and illiteracy to inequality. We’re making some progress. People and communities are getting some help.

And yet these questions still loom large over our work. So what combination of things needs to happen to actually solve some of these problems once and for all?

This is what the conversation about scale and impact in the social sector is about. It’s about moving from local solutions that are helping a specific population or community to finding broader solutions to the enormous social challenges that so many of our communities face. It’s about lifting up promising and proven ideas so they can have even more impact. And it’s about changing systems and policies on the basis of what’s working so we can produce lasting benefits for everybody.

In the hope of broadening the conversation in philanthropy about scale and impact, Grantmakers for Effective Organizations (GEO) launched the Scaling What Works initiative in 2010. We wrapped up the initiative at the end of 2013, and this special supplement in the Stanford Social Innovation Review is our opportunity to reflect with others on what we learned. It’s also a chance to try to capture the excitement, the discovery, and the debate as fresh attention and new resources are focused on how best to make progress on some of our most stubborn—and most urgent—social problems.

Redefining Scale

Growing impact is less about growing the size of a program or organization than it is about leveraging resources and relationships to achieve better results.

Although only a few foundations, mostly larger ones, explicitly say that scaling up solutions is a part of what they do, all grantmakers want their grantees to have a greater impact. Traditionally, this has meant supporting grantees to replicate their programs and grow their organizations so they can serve more people or broaden their reach in other ways. But GEO’s work over the last four years has shown that there are many ways to grow impact. Advocating for policy change, transferring technology or skills, or spreading a new idea or innovation all can lead to far-reaching and lasting change. As we heard in conversations with many grantmakers across the country, “We’re all doing it; we’re just using different words.”

What’s missing is a shared understanding among nonprofits, grantmakers, and government and corporate partners of the varying approaches to growing impact successfully. Making progress through many of these approaches will require a change in both mindset and practices. We need to push beyond a focus on growing individual organizations and set our sights on the ultimate change we seek, embracing collaborative action as a primary means to get there.

Until recently, organizational growth was the uniformly accepted measure of nonprofit success. “The organization got started in one school district in Boston and now it is in 23 states!” This kind of growth is impressive. Yet many of the organizations that were wildly successful at growing through program replication are now rethinking and retooling their work in hopes of growing their impact even further. The bottom line: The most important thing we need to scale up is not the size of an organization, but the results it achieves. The Bridgespan Group’s Jeff Bradach highlighted this point exactly when he observed, “The question now is, ‘How can we get 100× the impact with only a 2× change in the size of the organization?’”1

Seen in this way, growing impact is less about growing the size of a program or organization than it is about leveraging resources and relationships to achieve better results: significant and sustained benefit for people and communities. It’s about helping nonprofits “punch above their weight” and get outsized results compared to the resources they have at hand.

So let’s be clear about what we mean by scaling up. For GEO, it means “growth in impact.” The conversation about scale is therefore about the variety of ways in which nonprofits and their funders are creating more value for communities and making fast and substantial progress on the issues and causes we all care about. Approaches like catalyzing networks and supporting advocacy hold a great deal of promise because they offer ways to respond that are as sophisticated, complex, and far-reaching as the problems they seek to address.

Four Approaches to Grow Impact

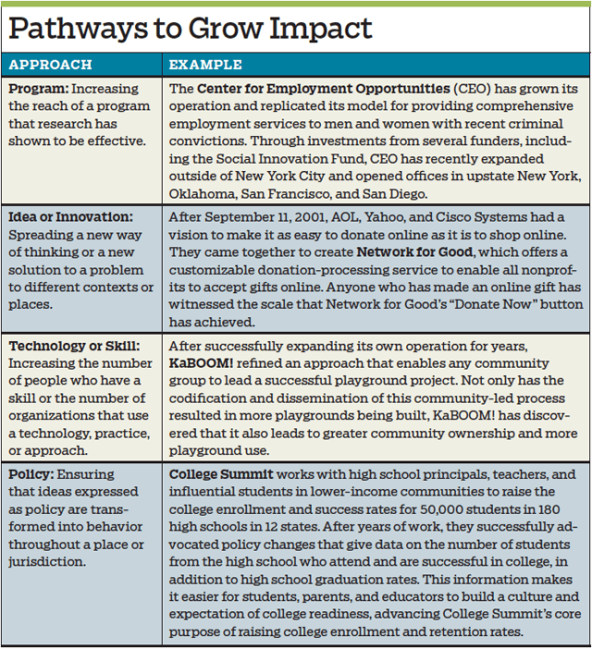

How can the nonprofit sector turn this conversation about scale into an agenda for action that will have a significant impact on the issues we care about? Through a major exploration conducted in collaboration with Ashoka, Social Impact Exchange, Taproot Foundation, and TCC Group, GEO sought to identify and describe the multiple pathways to impact and to match the pathways with specific grantmaker actions that support each approach. We also hoped to understand the grantmaking practices that impede progress. To illustrate the multiple pathways to grow impact, GEO has adapted a framework from Julia Coffman that originally appeared in The Evaluation Exchange. (See “Pathways to Grow Impact.”)

In our conversations with grantmakers and nonprofits, we have found that it’s important to acknowledge that innovation and impact are not the same. Innovation for its own sake isn’t the goal; rather, innovation is important insofar as it enables the expansion of social impact. Although it’s true that innovation can lead to breakthroughs, impact can also grow to the extent that we provide adequate resources to spread ideas and strategies that have existed for years. For instance, we have known for decades the dimensions that make mentorship powerful, particularly the frequency and consistency of interaction. Providing more resources to mentorship programs that have integrated this knowledge into their practice may not be innovative, but it clearly helps to grow social impact.

Changing the Conversation

I periodically serve as a guest lecturer at Northwestern University teaching undergraduate students interested in nonprofits. When I ask what their aspirations are for the future, by and large they say, “I want to start a nonprofit.” They don’t say that they want to make sure every poor kid gets the best possible education or that they want to defend health care as a universal human right. They want to found something—and frankly, it doesn’t matter what. If we are going to succeed in creating powerful advances, we need to turn this aspiration and mindset on its head.

Most high-performing nonprofits are led by inspiring, visionary leaders. Leadership is a vital ingredient for all efforts to grow impact. Yet the type of leadership the most effective social entrepreneurs are exhibiting, and the approach that will insulate their organizations against dependence on a single person or idea, is collaborative and networked. It’s what Robert Greenleaf called “servant leadership.” Ashoka Fellows coined the title “evangelist-in-chief” to describe a leader who inspires others to adopt a certain idea or approach that advances the social change an organization ultimately seeks.

Thorkil Sonne of Denmark is an example of this kind of leadership. In response to his son’s autism, Sonne founded the organization Specialisterne to employ high-functioning people with autism in information technology jobs. Seeking to serve a much larger number of people with autism spectrum disorders, he began to spend more time getting to know the work of related organizations, speaking publicly and connecting others to the work. His focus isn’t on growing his own organization per se; it’s on generating attention and support for the idea that people with autism have unique skills and can be highly successful in certain types of jobs. Thorkil Sonne, who founded two Danish organizations serving people with autism spectrum disorders, recognized the need for a leader dedicated only to developing and managing stakeholder relations and creating the public interest and will to take their concepts much further. He appointed a CEO, became chairman, and began to concentrate on generating the attention and support for his goal of securing one million jobs for people with autism and similar challenges worldwide.

As leaders in the social sector, we need to follow Sonne’s example and change the narrative about how to increase social impact. The key to success is recognizing and rewarding behavior that contributes to something bigger than any person or organization can achieve. In the past, the questions enterprising nonprofits struggled with may have been What’s our growth strategy? How many cities can we be located in five years from now? Today the questions are shifting to How can we amplify others’ efforts to advance our ultimate goal? What policymakers do we need to engage with to be successful in the broader social change we seek?

Next Steps for Grantmakers

For grantmakers seeking to increase social impact, it is important to remember that philanthropy can do harm. Insisting on open-and-shut evidence of impact or setting unrealistic deadlines for results can doom both a grantmaker and a grantee to failure. Nonprofits often confront enormous and complicated challenges that defy easy and fast solutions. When funding nonprofits, grantmakers should try to structure their investments in ways that help rather than hurt their grantees.

Regardless of one’s approach to growing impact, the same four fundamental grantmaker practices are crucial.

- Provide flexible funding in appropriate amounts over the long term. GEO and others have found again and again that nonprofits need flexible, reliable dollars over the long term. Providing larger grants and more general operating and multiyear support is crucial because it enables nonprofits to pay for the organizational infrastructure (staffing, systems, technology, etc.) that they need to succeed. David Carleton, director of Catalyst Kitchens, says Boeing’s flexible support has been important to his organization’s success. “They provided funding with no strings attached and no restrictions, just pure support for our mission and strategy. Not only was it critical financial support in our start-up year, but it was a vote of confidence that boosted morale and momentum—and sent a positive message to other funders.” Catalyst Kitchens provides food-service job training to build self-sufficiency among participants and combat food scarcity.

- Fund data and performance management capabilities. Nonprofits that seek to grow their impact need reliable data about what’s working, what’s not, and how to improve continuously. Grantmakers can help build this capacity by investing in grantees’ data collection and performance management systems. As part of its efforts to improve the lives of children in Detroit, the Skillman Foundation is supporting an organization whose exclusive focus is to provide nonprofit and government decision-makers with data and analysis so they can make more informed decisions. When used in the wrong way, however, data and performance management indicators can backfire. Grantees sometimes are punished for delivering worse-than-expected results when measured against unrealistic indicators. At other times funders and grantees waste precious time gathering data that do not lead to improvements.

- Invest in capacity building and leadership development that help organizations grow impact. Many grantmakers support nonprofit capacity building and leadership development, but often they do not provide the kind of help that nonprofits require—such as the ability of individuals and organizations to collaborate and build relationships. Funders can help build collaborative capacities by making connections for grantees; giving grantees the time, space, and special resources to carry out collective action; and providing general operating support as well as dedicated leadership development grants so they can help their staffs and boards develop the skills they need.

- Consider supporting movements as well as organizations. Throughout history, social movements have been important in advancing opportunity, well-being, and justice for all people. Today many grantmakers are shifting from solely supporting individual organizations and programs to supporting the multiple organizations and intersecting networks that constitute movements. This can be important and meaningful work, but it requires grantmakers to be patient and take the long view. The eight funders that compose the Civil Marriage Collaborative, a pooled fund tackling marriage equality, had the fortitude and patience to fight for the long term. It took 15 years of public education and community organizing to shift public perception of gay marriage in the United States. Today a majority of Americans support same-sex marriage. The collaborative has been providing funds since 2004 and gave $1.62 million in grants in 2013 to the groups on the front lines of that effort. (In November 2013 GEO hosted a conference exploring grantmakers’ support of movements. For more information on the conference, visit www.scalingwhatworks.org)

Looking Forward

Grantmakers and their grantees cannot be expected to take on the challenge of scaling up social solutions on their own. As always, government action will be an important driver of future progress. The Obama Administration launched the Social Innovation Fund (SIF) in 2009 as an experiment in public-philanthropic partnership to support the best community-based solutions. (See “From Innovation to Results.”) Other experiments under way in the federal government will yield more insights about the potential for collaborative action between governments, community organizations, and private grantmakers.

In order to make progress, all sectors will need to take a realistic look at their respective roles. As the SIF began its work, it was surprising to learn that the federal government saw philanthropy as a place to go to amplify its investments, and at the same time foundations and other “intermediaries” participating in the program saw the federal government as a source for the same. The reality, of course, is that private philanthropic resources will never come close to attaining the reach and impact of government, especially as government resources are redirected away from the social safety net or other services to help the poor.

The question for philanthropy and government alike is How can we deploy resources to the greatest effect? This question was the focus of a gathering for grantmakers that GEO and the Nonprofit Finance Fund convened in the fall of 2008. As the first clouds of the economic crisis were starting to appear, we had little idea how well-timed the conference would be. A comment at that gathering from Clara Miller (then president and CEO of the Nonprofit Finance Fund and now president of the F. B. Heron Foundation) has stayed with me. What she said, in a nutshell, was that the biggest change that could help the nonprofit sector operate more effectively is for philanthropy to better coordinate how it deploys financial resources.

Pioneers in the field understand this. For example, grantmakers like the Edna McConnell Clark Foundation, first through its capital aggregation campaign and now as an SIF intermediary, have made great strides in generating resources closer to the scale of the problems they are working to solve. The SIF itself, although not without its challenges (which have included a required private match that was too high), has certainly catalyzed joint funding and collaborative work throughout the United States.

As our collective thinking has matured and as we are able to draw from a larger base of experience, the common thread is the focus on growing impact rather than on growing organizations. GEO’s vision for the sector is one in which philanthropic leaders can’t imagine making strategic decisions in isolation. It’s a sector where grantees aren’t compelled to adopt a grantmaker’s measures of impact but rather are supported to identify and track the measures that make the most sense for them. In this future, grantmakers and nonprofits work in concert through wide-ranging networks, and the watchwords for philanthropy are flexibility, collaboration, and respect.

What will it take to achieve the wide-ranging changes we all want to see happen in our communities and our country? After four years of work alongside many of the pioneers in philanthropy and social change at all levels, GEO is confident we’ve landed on one thing it takes. It takes grantmakers who are committed to working with nonprofits to ensure that they have everything they need to grow their impact over time.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Kathleen P. Enright.